Table of Contents

Ryan McMaken

Ryan McMaken is executive editor at the Mises Institute. Send him your article submissions for the Mises Wire and Power and Market, but read article guidelines first. Ryan has a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado.

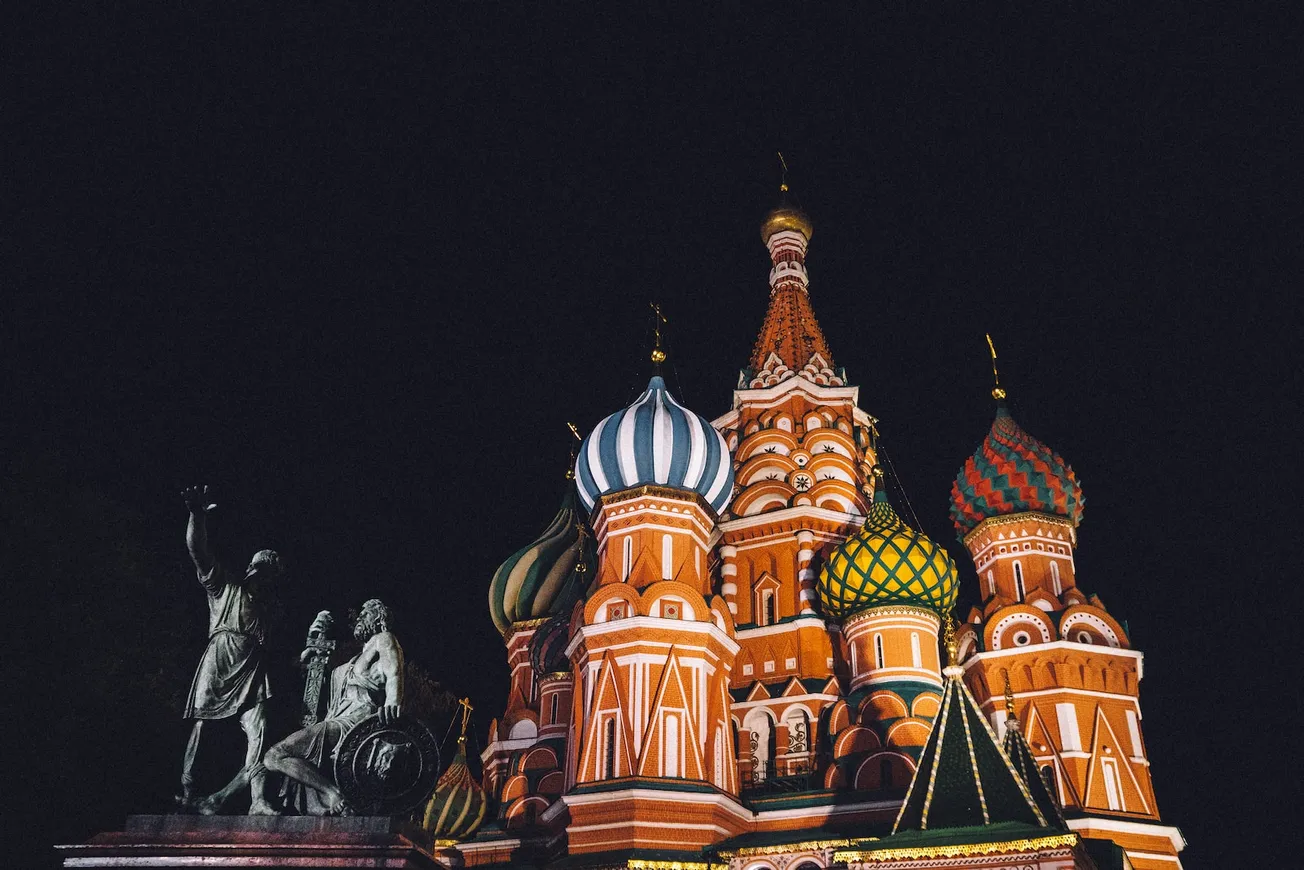

Pope Francis made headlines when he described the Russian Empire as “enlightened” and invoked the names of two expansionist Russian czars as examples of Russia’s “great culture.” In impromptu remarks, Francis said to a group of Russian Catholics, “You are the heirs of the great Russia: the great Russia of saints, of kings, the great Russia of Peter the Great, of Catherine II, of that great, enlightened Russian empire, of great culture and great humanity.”

Francis was quickly savaged among pro-Ukraine groups for these remarks, but for very superficial reasons. Essentially, Francis’s comments were evaluated almost totally in terms of how they related to the current Russian regime and the ongoing Russo-Ukraine war. Few specifics were mentioned about either Peter I or Catherine II—both often sharing the epithet “the Great”—except that they reigned during a time of Russian military conquests, and some of those conquests included lands later incorporated into modern Ukraine.

But the real offense committed by these long-dead rulers is that Russian president Vladimir Putin is said to view them as examples of laudable Russian rulers of the past. Putin has explicitly praised Peter I while various Putin critics maintain he has similar affinities for Catherine II.

Consequently, Francis—in making what appeared to be little more than words of encouragement to a small Russian religious minority—was accused by Ukrainian state spokesmen of repeating “Russian nationalist talking points.” Moreover, Francis has long been a target for the Ukrainian state and its supporters, as Francis has long avoided—to his credit—jumping on the NATO bandwagon which pushes a protracted war in Ukraine while condemning all things Russian.

But what are we to think of the legacy of Peter I, Catherine II, and the Russian Empire in general? Certainly, we should not take our cues from NATO’s useful idiots in Ukraine like Volodymyr Zelensky who would have us believe that almost everything can be understood via the sentiment “Ukraine good, Russia bad.” Similarly, it would also be absurd to judge episodes of Russian history by the standard of what Putin thinks of them.

Many Wars against “Ukraine” Were Really Wars against Poles and Turks

The limitations of reading everything through the lens of “what did Russia do to Ukraine?” can be seen in the fact that by doing so, countless relevant facts are lost in the process. For example, portraying the conquests of Peter I and Catherine II as wars primarily against ethnic Ukrainians is stretching the truth beyond recognition. Their wars in the region were primarily wars targeting the Ottoman Turks with much of the focus being on regions that are today the Crimea and southeast Ukraine. Yet, at the time, these lands were not “Ukraine,” but were under the rule of Islamic princes in a polity known as the Crimean Khanate. Moreover, the Crimean Khanate and its allies—in the centuries before their final elimination by Catherine II— carried out a vicious slave trade against neighboring areas. Tens of thousands of ethnic Ukrainians were victims of this slave trade, thus it can hardly be said that war against the Crimeans in the eighteenth century was a “war against Ukrainians.”

On the other hand, both Peter I and Catherine II carried out wars of conquest in what is today northern and central Ukraine. Unlike Crimea and neighboring areas, these more northerly areas could more accurately be described as a type of Ukrainian heartland. But again, we must note that the Russian gains in these regions under Peter and Catherine did not abolish Ukrainian independence. Indeed, no such independence existed. Rather, Russian conquests largely came at the expense of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which held much of northern and western Ukraine under a Polish ruling class.

On this, one could certainly argue that rule by Poles was preferable to rule by Russians. The Commonwealth was far more decentralized than the Russian state and allowed more local independence. Moreover, it appears that in many areas, the Polish ruling class did not “Polonize” the local Ukrainians as aggressively as the Russian state sought Russification. Nonetheless, many Ukrainian nationalists would disagree with the notion that rule by the Poles was kind and gentle. By the twentieth century, some believed “four centuries of Polish rule had left particularly destructive effects” on many areas that were populated by the Ukrainian minority within the Commonwealth. In the words of Ukrainian historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky, the Polish rulers “assiduously skimmed everything that could be considered the cream of the nation, leaving it in a state of oppression and helplessness.”

Many similarly oppressive acts against the Ukrainian minority by the Russian state could be listed as well, of course. But the facts also illustrate the shallowness of trying to cast Russia’s war on its western frontier as a simple matter of Russia against independent Ukrainian communities. Precious few communities existed, and many of these wars “against Ukraine” would just as accurately be called wars “against Poland and the Turks.”

The “Enlightened” Rule of Catherine II and Peter I

Nonetheless, even a stopped clock is right twice a day, and Francis’s Ukrainian critics aren’t exactly wrong about the realities of rule under the “great” czars of old. While efforts to craft the legacies of Catherine and Peter around Ukraine are ham-fisted, to say the least, there are plenty of other reasons why Francis’s efforts to shower praise on these past czars are highly suspect. Where did Francis even get these ideas? Francis has admitted that his comments praising Catherine II and Peter I came from little more than some lessons he received in school many years ago. That is, it is likely that Francis was simply repeating stale talking points that were popular in the mid-twentieth century which maintained that political rulers who “modernized” their countries were great examples of enlightened government. For modern day totalitarians and social democrats, this may seem reasonable. These people love “modernization” which often means secularization, centralization, and creating a more “efficient” state bureaucracy.

From the point of view of promoting human rights (i.e., natural rights such as life, liberty, and property) however, there’s very little good that can be said about the type of modernization or enlightenment that occurred under Catherine II or Peter I.

It is true that Catherine II was briefly converted to the idea of free trade, but she soon abandoned such efforts. What better characterizes Catherine’s rule are her efforts to rob countless peasants of their few political and economic rights, thus reducing them to the level of serfs. As Roger Bartlett noted, “The middle decades of the eighteenth century and the reign of Catherine II are often said to be the apogee of the Russian servile regime: as the peasants lost juridical status, the power and privilege of the nobility grew.” Catherine enserfed whole classes of the population which had previously been free. It’s hard to see what’s so modern or enlightened about that.

Catherine, however, was following in the footsteps of Peter I who perhaps invented the idea of “modernizing” Russia to be more like western Europe. As Ralph Raico has put it, “Every once in a while, a ruler comes along and says, ‘heavens, we’re so far behind Europe, we have to do something about it, let’s modernize.'” Raico noted, however, that since Peter had no appreciation for the western institutions of private property, he could not possibly re-create the most important aspects of what made Europe modern. Understandably, Peter was very impressed with the high standard of living enjoyed by the Dutch. Yet, Dutch prosperity had been built on relatively free trade, on stable property rights, and political decentralization. Peter introduced none of these things in Russia.

Rather, much of Peter’s modernization was purely ornamental in nature. He was impressed with the French court and sought to copy the trappings of French absolutism in many ways. He taxed beards, for instance, in an effort to get Russian nobles to look more like French nobles. He pursued European-inspired building projects as well, but in the process of building his new “modern” capital in St. Petersburg, he relied primarily on slave labor.

Francis’s comments on these czars display his ignorance of historical realities. On the other hand, Francis is right to refuse to vilify Russians in general. As Raico noted in the process of describing the despotism of the Russian state, “the Russian people are one of the great peoples of Europe.” Yet, “Everybody, in a way, is a victim of the history of the society he’s born into.” If rulers like Catherine and Peter are great representatives of Russian “enlightenment,” the Russian people are victims, indeed.