Table of Contents

It’s been conveniently forgotten now, but 60s hippy rock star Neil Young caused quite a kerfuffle in the 80s, when he backed not only Ronald Reagan, but nuclear weapons. Young claimed that nuclear weapons were a necessary deterrent against WWIII.

It seems crazy and counter-intuitive, but it’s true: the most destructive weapons humans have ever devised have coincided with the most peaceful era in human history.

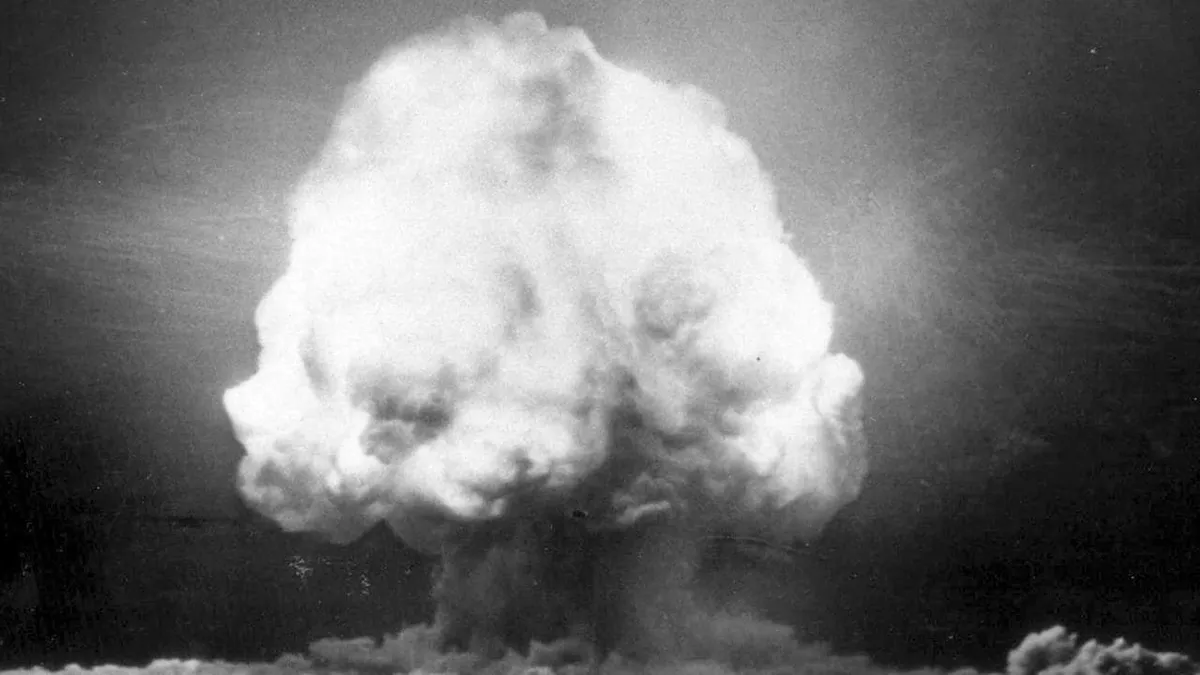

Seventy-five years ago today, the world’s first atomic explosion, codenamed Trinity, jolted the New Mexico desert just before dawn.

Gathered to witness the detonation was an extraordinary conglomeration of intellect. There were European emigres Edward Teller, Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi as well as Berkeley’s Ernest Lawrence and Harvard’s James Conant. The project was led by physicist Robert Oppenheimer and US Army Major General Leslie Groves.

If only the US could establish an equally strong partnership among the military, industry and academe today.

The device, nicknamed “the Gadget”, was less than 2m in diameter and covered with cables, metal fuse boxes and masking tape, not at all like today’s immaculate weapons. It could have been a component of an elevator. The plutonium core was transported separately in the back seat of an army sedan. Oppenheimer didn’t want to risk blowing up any towns along the way.

There was a betting pool among the scientists on the bomb’s yield (its TNT equivalent in kilotons). Norman Ramsey, the pessimist, guessed low at zero. Teller wagered high at 45kt. Nobel laureate Isidor Isaac Rabi won the pool at 18kt. He entered late and 18 was the only number available.

All doubt disappeared when the Gadget ignited with a blinding flash charging upward into the stratosphere.

Despite Oppenheimer’s gloomily awed pronouncement that, “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”, the world was not destroyed. In fact, as Steven Pinker documents in The Better Angels of Our Nature, the post-WWII era has seen a stunning decline in violence and war. Not eradication, of course. But a decline unprecedented in human history.

Admittedly, this is a continuation of a trend that’s spanned human history for thousands of years. Contrary to the Rousseauian fantasies of the green-left, tribal societies are unbelievably violent. As human social organisation progressed through feudalism to the post-Westphalian nation-state, violence declined. The first half of the 20th century was a brutal interruption of that trend – although even the “haemoclysms”, as Pinker dubs them, of the two World Wars were still far from, per capita, the worst outbreaks of human violence in our history.

Trinity signalled the end of the haemoclysm of WWII.

A city centre could be destroyed in an instant. But the historic event remained a closely guarded secret for two weeks. President Harry S. Truman, in Potsdam for the post-VE conference with Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill, was handed a telegram that evening: “Operated on this morning. Diagnosis not yet complete but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations”[…]

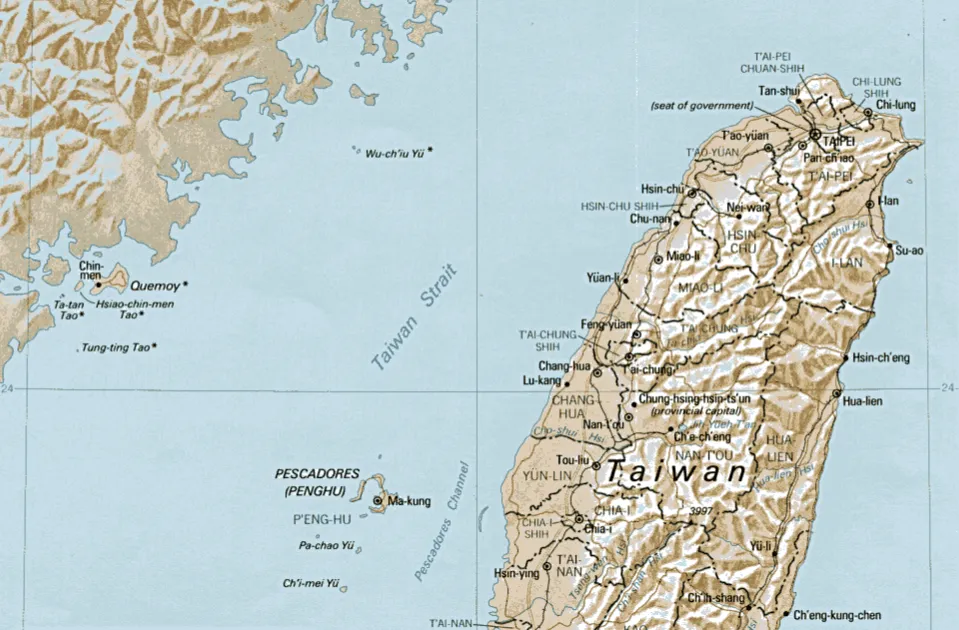

Four hours after the blast, almost 1500km away, another bomb, “Little Boy”, embarked from Hunter’s Point in San Francisco on the USS Indianapolis, bound for the B-29 base on the island of Tinian. On August 6, it destroyed Hiroshima. The Manhattan Project ($US2.2bn) and B-29 bomber ($US3bn) were the war’s most expensive projects.

The reaction within Allied countries to the atomic bombings of Japan was relief. They ended the most brutal war in history without an invasion of the Japanese home islands, which would have resulted in millions of casualties.

Even then, though, the intelligentsia were all-too-willing to undermine liberal democracy in favour of the brutal totalitarianism of Marx and his murderous followers.

When Truman told Stalin the US had a powerful new weapon, the Soviet dictator showed no surprise. Truman didn’t know that Stalin had been kept in the loop throughout the project by two spies in New Mexico, the more important being Klaus Fuchs, a German exile and a communist.

Even as the smoke was still pouring from the rubble of Hitler’s bunker, British prime minister Winston Churchill ordered plans drawn up for a hypothetical invasion of the Soviet Union, the perhaps appropriately-named Operation Unthinkable. The trigger would have been enforcing Stalin’s Yalta pledge of free elections in Poland. However it might have changed the course of the second half of the 20th century, the plan was abandoned by the war-weary West. The greatest obstacle was the Soviets’ numerical supremacy: how nuclear weapons would have tipped the balance does not appear to have been considered.

In any case, within a few years, the chance was gone – in large part due to the efforts of the pro-Communist moles in the American program.

The US held a monopoly on operational nuclear weapons, until the Soviets detonated “First Lightning” on August 29, 1949 — a direct copy of the bomb dropped on Nagasaki four years earlier, thanks to the spy Fuchs.

With the abandonment of Operation Unthinkable, the world quickly settled into the Cold War detente. Yet, even as East and West lined up bigger and bigger armies against each other, the dreaded Third World War never came.

Thanks to nuclear weapons.

Besides saving millions of lives, Hiroshima and Nagasaki demonstrated beyond doubt the shocking power of the new weapons. The use of nuclear weapons quickly became unthinkable. Mutually Assured Destruction might have earned the acronym “MAD”, but it made grim sense. What was the point of launching a war that no-one could possibly win?

The nuclear club has expanded since then. Though dozens of wars and skirmishes have been fought since Nagasaki, killing millions, no nuclear weapon has been used in anger.

And that’s the seeming paradox of the nuclear age. Humans now possess the means of almost certainly destroying ourselves utterly. Consequently, no one dares use it.

Instead, we’ve had to learn, falteringly, with many backwards steps, to find ways other than war to solve our differences.

We’re a long way from ending war, if we ever will. But we’ve come a long way from the brutal Hobbesian “state of nature”. All thanks to the most fearsome weapons ever devised.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.