Table of Contents

Carolyn Moynihan

mercatornet.com

Carolyn Moynihan is the former deputy editor of MercatorNet

Warning

Long read: 1880 words

Fifty years ago, United States Supreme Court judges invented a right to abortion for all America after feminists (and not a few men) insisted that, for women to stand as equal citizens with men, they had to be able to kill their unborn children.

Today, the heirs of this initiative are marching in the streets, outraged that the Roe v Wade ruling may be overturned and that those who want abortion on demand may have to explain what kind of a right it is.

The “rights of women” has a long history, at least 200 years, but “abortion rights” were never on the agenda of the campaigners until the mid-20th century. Prior to that, women’s rights advocates opposed infanticide and abortion – which certainly occurred with some frequency – as immoral, the acts of a desperate women, and sought to address the causes.

In 1916 Margaret Sanger’s first handbill advised: “Do not kill, do not take life, but prevent.” And as late as 1964 Planned Parenthood had a pamphlet stating: “An abortion kills the life of a baby after it has begun. It is dangerous to your life and health.”

What changed to make women turn against themselves in this radical way?

Many things; but crucially, according to a new book, the concept of rights became detached from the concepts of human dignity and excellence, both intellectual and moral.

For the women’s movement, argues feminist legal scholar Erika Bachiochi, this has meant abandoning the moral vision that inspired its early leaders. Instead, it has thrown in its lot with the sexual revolution that began in the 1960s and the individualism of the market.

The effect has been to cheapen sex, devalue parenthood and the work of the home and disadvantage many women, men and their children.

By contrast, the vision in question is one that demands sexual self-mastery of both men and women. It sees men and women not merely as individuals but as persons embedded in relationships, starting with the family. It requires mutual affection between husband and wife and for their children, and equal engagement by husband and wife with the family project. It puts duty before rights, and virtue before power.

The moral vision of an early feminist

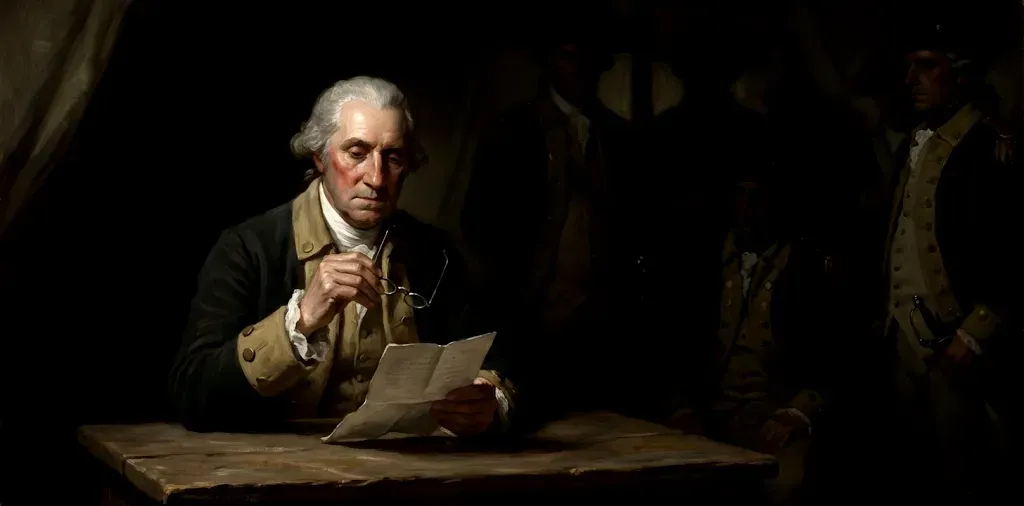

In The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision, Bachiochi traces the history of this idea from its brilliant articulation by the late-18th century English writer Mary Wollstonecraft, through its development then eclipse in the American women’s movement – and its persistence in the work of US scholars such as Harvard legal luminary Mary Ann Glendon.

Wollstonecraft’s short life (1759 to 1797) spanned the American and French revolutions and the ferment of ideas about representative government and the “rights of man” that surrounded these events. She promoted both principles, but from a moral perspective that has been largely ignored in recent times.

In fact, her best-known work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), “is scarcely about rights at all”, says Bachiochi. It is about duty and virtue.

Like her mentor, Unitarian preacher Richard Price, Wollstonecraft wanted liberty and equality for all men and women not as ends in themselves, but as the necessary means to higher human ends: intellectual and moral excellence, or, wisdom and virtue.

Only with equal rights before the law, and an equal, liberal education, could women pursue such a life, she maintained. Women needed to develop their God-given intellectual powers and be able to think independently in order to be virtuous.

Unfortunately, Wollstonecraft’s unconventional personal life (whose details are contested) has tended to distract both puritans and feminists from her philosophy.

‘The want of chastity in men’

By “virtue” Wollstonecraft did not mean only the virtue of chastity, which Rousseau had popularised as the quintessentially “feminine” virtue. However, she certainly wanted more chastity, especially among men:

“For I will venture to assert, that all the causes of female weakness, as well as depravity … branch out of one grand cause – want of chastity in men.”

Here we can see one of the chief mistakes of modern feminism: claiming for women the “freedom” to be as unchaste as men, instead of demanding a higher standard of male sexual behaviour – except as an afterthought (MeToo) and then only for the sake of “consent”.

Wollstonecraft’s own era was permissive when it came to men’s sexual behaviour. Her radical idea was that chastity in both sexes would lead to virtuous friendships of mutual trust and collaboration.

By fulfilling their duties, she insisted, married men and women would grow in affection for each other and their children, and all would develop the moral strengths essential to the happiness of individuals and society: self-mastery, humility, benevolence and “the whole noble train” of virtues.

“If you wish to make good citizens, you must first exercise the affections of a son and a brother. This is the only way to expand the heart; for public affections as well as public virtue must ever grow out of private character…”

Women and work

Although the rearing of young children seemed to Wollstonecraft “the peculiar destination of women”, she held that women could not be confined to the domestic sphere, nor be shut out of great enterprises.

“Extraordinary” women might forgo marriage and family life altogether to focus on professional enterprises. However, she pointed out, “the welfare of society is not built on extraordinary exertions” and for mothers, domestic duties must come first.

She urged women to take the work of the home – primarily the formation of the children in virtue – seriously, with a sense of order and determination: “Whoever rationally means to be useful must have a plan of conduct … much resolution” and “a serious kind of perseverance” in this work. Under the right conditions the mother could create time for other work.

But men must make an equal effort.

A woman would not be successful and happy in her familial duties unless men turned their first affections there too. Yet equality was not a matter of equally shared roles, as today’s feminists insist, but of virtuous, benevolent dispositions.

Wollstonecraft viewed fatherhood as deeply transformative of men: “The character of … a husband and a father, forms the citizen imperceptibly, by producing a sober manliness of thought, and orderly behaviour…”

Sociological research today has found the same thing, notes Bachiochi:

“Men who are husbands and fathers are more successful at work and have better health and less substance abuse issues and less criminal activity. And fathers who are attentive to their children – and even more importantly, to their children’s mother – not only have happier children, but the children have happier mothers.

“Indeed, studies have found that the single best predictor of a happy mother is an emotionally attentive father.”

In America: From domestic pillar, to market worker

From all this it is clear that the work of the home was, for Wollstonecraft, the most important work mothers and fathers can do.

Her views were influential among early women’s rights advocates in America. There, although the domestic sphere remained largely in the hands of women and the public sphere in the hands of men, women’s solid moral and practical work in the home and community was one of the pillars of the young republic in its agrarian phase and was recognised as such.

Roles were distinct but inter-dependent and balanced, though women’s legal status left some vulnerable to domestic tyranny. Hence the battle for joint property rights and other marriage law reforms.

With industrialisation and the shift of men’s work away from the home precinct and the community, however, came a progressive devaluation of the work of the home – in particular the nurturing of virtue – and eventually of the family itself.

As industrialism and commercialism gathered steam, women (as well as their children) from the ‘lower class’ followed men into the factories, and the efforts of many women’s rights campaigners turned to the protection of women workers, and then progressively to equality of pay and opportunity.

The unstoppable trend of the last 100 years (with a brief return to domesticity in the 1950s) has been to absorb virtually all women into the job market, even those with young children. Even many of the latter who would rather be caring for their children at home. The result is what is increasingly recognised as a caregiving crisis.

Market equality vs motherhood

This triumph of the market over home and family has been made possible, of course, by “effective” contraception and, as the people organising protests against the US Supreme Court right now are well aware, legalised abortion.

Bachiochi describes these developments of the 1960s and 1970s focusing on two highly influential figures: Betty Friedan and Ruth Bader Ginsberg. She gives them credit for their positive contributions – Friedan for highlighting the “feminine malaise” of post-war, consumerist America, and Ginsberg for her legal wins against sex-role stereotyping and discrimination in the workforce – while pointing out that both women, sooner or later, made progress for women contingent on a “right” to abortion.

For Ginsberg, it was a matter of “sex equality”. Following the Roe v Wade decision, she defended abortion as allowing “a woman’s autonomous control of her full life’s course … her ability to stand in relation to man, society and the state as an independent, self-sustaining, equal citizen”.

But in proposing the autonomous individual as the model for women (men, presumably, having already achieved this status), the late Supreme Court judge completely overlooked what Bachiochi calls the “deep sexual asymmetry” between men and women.

The stubborn fact at the bottom of all the arguments about women’s rights and woman’s role is this: while both a man and woman are needed to generate a new human being, only the woman bears the burden of gestation and birth.

Women, at least those who have bought into the sexual revolution, cannot just walk away from motherhood as men can walk away from fatherhood. They must make a choice.

Ironically, as Bachiochi points out, the right to choose motherhood (or not) without requiring a choice not to have sex – that is, to have an abortion when contraception fails or is simply neglected – has put the whole burden of choice regarding parenthood back on women.

Whatever else abortion achieves – population control, fewer poor women on welfare, more women in the workforce – it is not equality.

It is not an answer to the caregiving crisis among those who do have children.

And it is very far from being the answer to this century’s crying need for a virtuous citizenry who can live in peace with one another.

For that we need the realism and moral vision of a Mary Wollstonecraft.

Happily, we have not lacked such visionaries in our own time.

The second part of this review will cover the last two chapters of Erika Bachiochi’s fascinating and important book, in which she deals with the dignitarian vision of the internationally acclaimed legal scholar Mary Ann Glendon, and re-imagines “feminism today in search of human excellence”.