Table of Contents

Juliet Moses

Juliet Moses is a New Zealand lawyer specialising in trusts and estates work with wide experience. She is also actively involved in community organisations and is a trustee of the Astor Foundation, working to maintain a peaceful and harmonious society in New Zealand and addressing issues arising from extremism and religious and ethnic hatred.

New Zealand recently voted at the UN General Assembly to support a resolution concerning Israel and Palestine that our officials admit has many flaws. Their explanation for why we voted this way was as noteworthy as the resolution itself, and reveals disturbing illogic and moral confusion.

The resolution was drafted by the Palestinian delegation and sponsored by many states that do not recognise Israel and are not known as leading lights in human rights, including Algeria, Iraq, Pakistan, Malaysia, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Bangladesh and North Korea.

The resolution’s 19 paragraphs do not once mention Hamas (a proscribed terrorist entity in New Zealand and an Iranian proxy) that triggered the current war with its barbaric October 7 invasion of southern Israel, or the over 100 hostages it continues to hold underground in Gaza. Nor does it mention Palestinian terrorism or violence or make any demands of Palestinian leaders.

Instead, it erases Jewish historic and legal claims to the land beyond the armistice lines that resulted from the failed war of annihilation by five Arab states against the nascent state of Israel in 1948 and gives Israel 12 months to withdraw from those lands.

This means Jews would be ethnically cleansed from land that is the cradle of Jewish civilisation, has had a Jewish presence for 3000 years and been the focal point of our liturgy and festivals. It includes the eastern part of Israel’s capital city Jerusalem, in which is situated the Jewish people’s holiest site (the Temple Mount), as well as the Western Wall, the Jewish Quarter, and Hebrew University.

October 7 Invasion

Israel, one-12th the size of New Zealand, with the south largely uninhabited since Hamas’ October 7 invasion, and the north largely uninhabited since another Iranian proxy Hezbollah started firing rockets at it from Lebanon on 8 October, would have indefensible eastern borders with a width at its narrowest point of some 15kms.

The resolution purports to endorse a recent advisory (non-binding) opinion by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s judicial arm.

That opinion in itself was deeply flawed but also far more nuanced, limited and complicated than the resolution would suggest. It followed a request for an opinion from less than half the UN member states, which presupposed that (among other things) Israel is illegally occupying Palestinian land.

All but one of the 15 of the ICJ judges gave individual opinions, and often disagreed between themselves on the reasons for the conclusion they reached as to that and other issues and what their consequences were. Six judges found that the proceedings and opinion had failed to consider the whole legal and historical context of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Most judges disregarded prior opinions on the ICJ’s jurisdiction to consider a bilateral dispute without the consent of both parties, the British Mandate that recognised the “historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country” after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire as well as the Oslo Accords (both binding instruments under international law), and the important principle of uti possidetis juris.

That is one of the main principles of customary international law intended to ensure stability in the demarcation of new states (for example, those emerging from Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union).

Dissenting Opinion

The ICJ’s Vice President Julia Sebutinde (pictured) gave a dissenting opinion in which she found the Court had misapplied the law of belligerent occupation and adopted presumptions without a prior critical analysis of relevant issues, including the application of the principle of uti possidetis juris, the question of Israel’s borders and its competing sovereignty claims, the nature of the Palestinian right of self-determination and its relationship to Israel’s own rights and security concerns.

“It is bewildering that New Zealand would vote for a resolution that it was at pains to point out is so flawed. More bewildering were the befuddled statements that Peters gave to media.”

As a result, she found that the ICJ opinion “is tantamount” to a one-sided, “forensic audit” of Israel’s compliance or non-compliance with international law, that does not reflect a comprehensive, balanced, impartial, and in-depth examination of the pertinent legal and factual questions involved and “overlooks the intricate realities and history of the territories and populations within modern-day Palestine”.

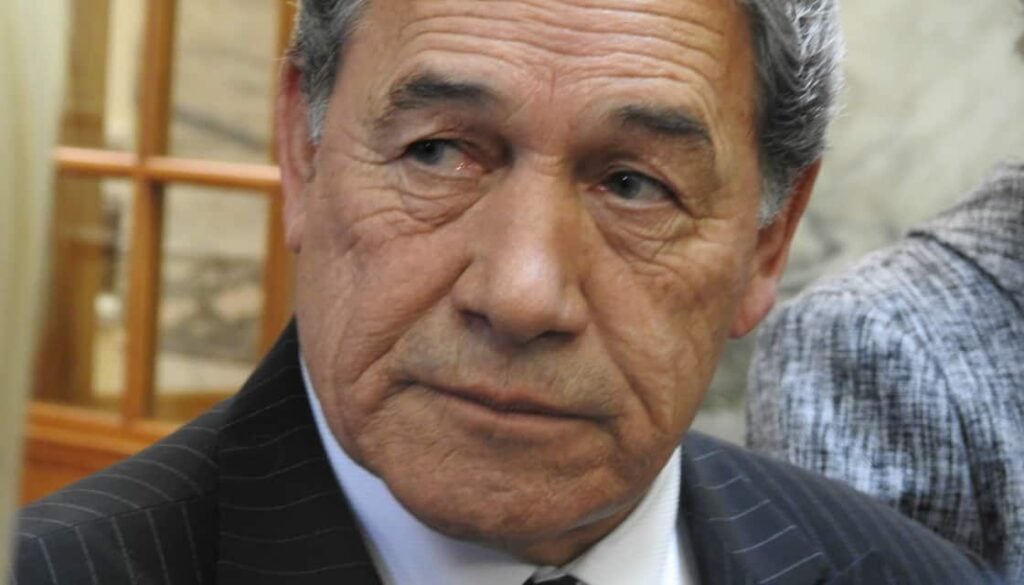

Whether or not Foreign Minister Peters (who did not put the vote to Cabinet, likely in breach of the Cabinet Manual) was cognisant of the flaws of the ICJ opinion, he did acknowledge some issues with the UN General Assembly purporting to adopt it.

“Imperfect” Peters

The first line in the explanatory statement from Minister Peters says New Zealand supported this resolution “with some caveats”. Calling it “imperfect”, it noted that “New Zealand held concerns about aspects of the text of the resolution”, that the 12-month timeframe for implementation is “frankly unrealistic” and that “We are also disappointed that the resolution goes beyond what was envisaged in the advisory opinion in some respects.”

Other states abstained from or opposed the resolution over such concerns, even if they endorsed certain aspects of it.

While it was supported by 124 countries, 14 opposed it (including the United States, Fiji and Tonga) with 43 abstentions (including Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, Ukraine, India, and Germany).

Australia explained it abstained because it went beyond the scope of the ICJ opinion. The UK abstained because “the resolution does not provide sufficient clarity to effectively advance our shared aim of a peace premised on a negotiated two-state solution: a safe and secure Israel alongside a safe and secure Palestinian state”. And Canada explained that: “Canada cannot support a resolution where one party, the state of Israel, is held solely responsible for the conflict.

“Canada supports Israel’s right to live in peace with its neighbours within secure boundaries and recognizes Israel’s right to assure its own security.

”There is no mention in the resolution of the need to end terrorism, for which Israel has serious and legitimate security concerns” and it seeks to “uniquely isolate Israel” through the economic and diplomatic boycott and sanctions it calls for.

It is bewildering that New Zealand would vote for a resolution that it was at pains to point out is so flawed. More bewildering were the befuddled statements that Peters gave to media.

One outlet reported him saying: “We are saying [Israel’s] gone far too far now in the pursuit of their defence, in the misery they have created for innocent people.” And another that (referring to Hamas): “the source of Palestine’s misery is those people who came in one day who murdered 1200 people and stole over 100 hostages, took them to their country and are now using them as bargaining chips”.

Why then vote for a resolution that fails to condemn Hamas (no UN resolutions have condemned it), emboldens it and ignores Israel’s security concerns and the hostages? And that requires Jews to leave Jersualem?

New Zealand’s UN representative said: “A two-state solution needs to be the product of negotiations” (a position that is consistent with past governments). So why vote for a resolution that disincentivises and bypasses any negotiations by pre-determining their outcome and absolving the Palestinians of any responsibility or agency, by requiring nothing of them and meeting their demands?

What people, principle, policy or posturing require supporting a resolution that is not workable, evidently hard to justify, irreconcilable with New Zealand’s longstanding position, imperils the state in the Middle East with values and freedoms most closely aligned to ours, and puts us at odds with our allies and closest friends?

In 1980 then Prime Minister Robert Muldoon observed that “our foreign policy is trade”. I don’t know if that is the answer, but we deserve to know what is.

This article was republished by the Israel Institute of New Zealand.