Table of Contents

Bryce Edwards

I am Political Analyst in Residence at Victoria University of Wellington, where I run the Democracy Project, and am a full-time researcher in the School of Government.

The assassination attempt on US presidential candidate Donald Trump is a reflection on how toxic and polarised politics has become in that country. When people attempt to carry out assassinations, we can hope that these are isolated aberrations, but the fear is always that they reflect a more comprehensive breakdown of democratic politics.

New Zealanders will be pleased that it hasn’t become a significant part of electoral politics here. However, it would be naïve and complacent to believe it couldn’t happen. This is a reminder that New Zealand needs to be able to deal better with political differences before the threat of political violence escalates.

Is New Zealand following the US down the path of aggressive political polarisation?

Broadcaster Ryan Bridge of Newstalk ZB asked: “Is there a lesson in Trump’s shooting for NZ’s political leaders?”.He thinks that politicians should take a lead in toning down some of their more violent and provocative language.

He points to the likes of David Seymour joking about blowing up government departments, Chloe Swarbrick chanting slogans that many Jewish people interpret as calling for Israel to be forced out of the Middle East, and Te Pati Maori MPs accusing their opponents of being white supremacists. Such “extreme political language can raise the temperature and cause violence”, according to Bridge.

He argues that although most physical protests are “pretty minor, a dildo to the face, lamington on the head”, there is the potential for this to escalate to less humourous attacks on politicians. Therefore, those across the political spectrum need to take heed of where things can end up – looking at what happened in the US at the weekend.

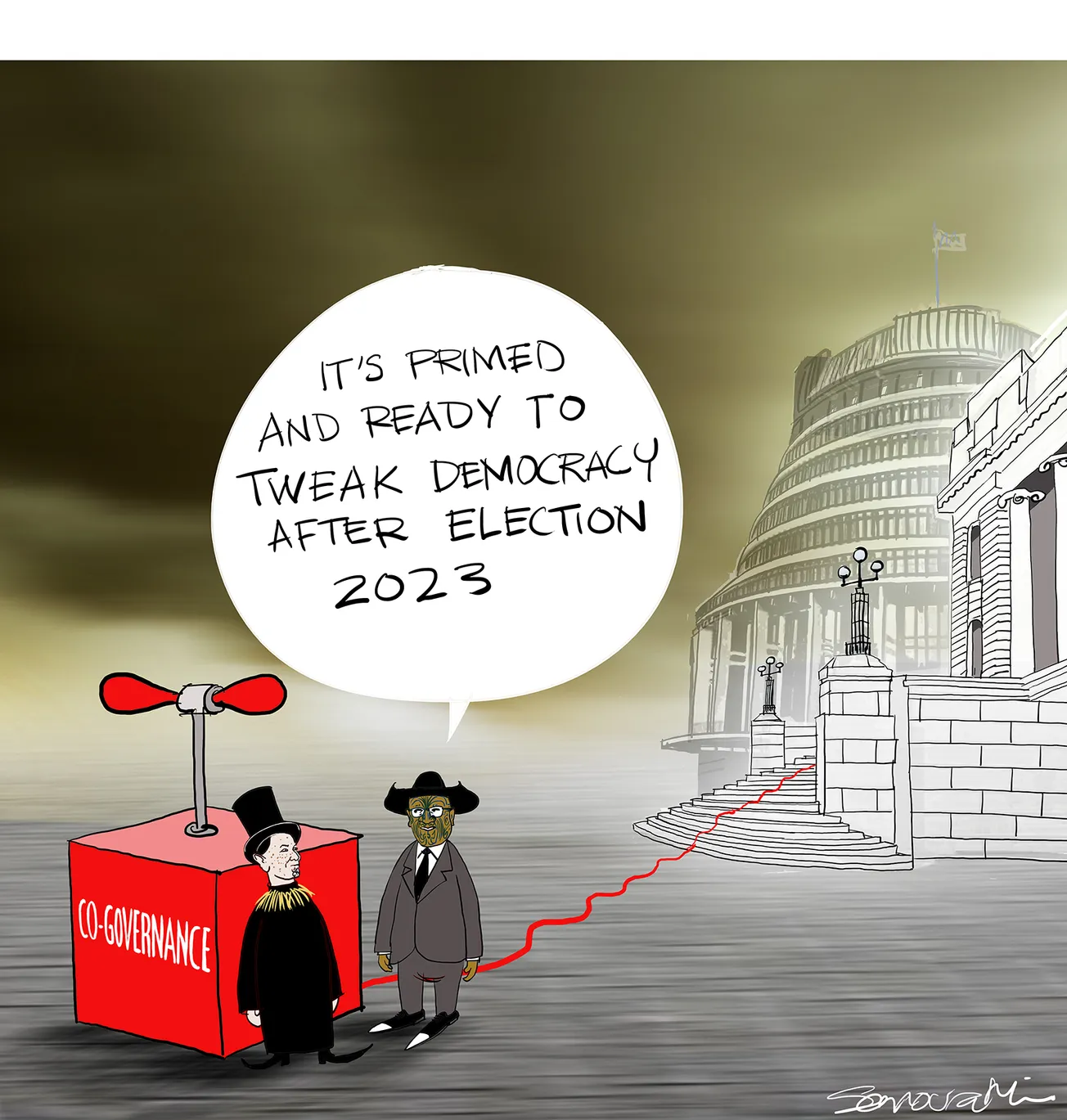

Race politics are the most polarised

The area where New Zealand politics is most polarised and often verging on political violence is regarding ethnicity, racism, and Treaty of Waitangi politics. Arguments over these issues have been escalating wildly.

On Sunday, the co-leader of Te Pati Maori, Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, continued her strong rhetoric about race on TVNZ’s Q+A in an interview with Jack Tame. She claimed “We’ve got a Government that is genocidal, ecocide, we know that they are white supremacists.” When Tame pushed back against this, challenging Ngarewa-Packer about whether the new Government is really “genocidal” towards Maori, she replied, “There’s no if, they are.”

Some would argue that such rhetoric escalates tensions, increases polarisation, and makes political violence more likely. For example, National-aligned political commentator David Farrar says today: “this is extremism, that promotes violence. If you keep telling 20 per cent of the population that the Government wants to commit genocide and exterminate them, then of course that will lead to extremism and violence. It is beyond the realm of acceptable discourse from an MP, let alone a co-leader. It is far more extreme than anything Trump or the most left representative in the US says.”

Farrar challenges the Labour and Green parties to definitively distance themselves from these sorts of statements by stating that they will “rule out Te Pati Maori playing any role in a future Government unless they drop their violent extremist language”.

Interestingly, however, Debbie Ngarewa-Packer has also complained about rising threats and threats of violence in politics and also says that politicians are partly to blame. She told the Herald last year: “I think sadly because of the polarisation, the way that politicking has been going, there hasn’t been a good discussion, there hasn’t been calm called by many leaders.”

Survey of MPs about their safety

Although politicians are driving up the political heat in New Zealand at the moment, they are also the potential victims of those increased hostilities. There should be no doubt that parliamentarians are facing more threats and toxicity than they used to.

University of Otago academics published an important survey research of New Zealand MPs in April in the international journal Frontiers in Psychiatry. This surveyed 54 MPs during and after the Covid pandemic and found that they had experienced a disturbing rise in harassment and threats. Nearly every respondent in the survey reported harassment ranging from communications on social media to physical violence. A similar survey was conducted in 2014 and found much less in the form of threats and harassment.

Reporting on the survey research, the Herald’s Katie Harris stated: “The research revealed 98 per cent of the 54 MPs surveyed reported experiencing harassment, 40 per cent said they were threatened with physical violence, 14 per cent with sexual violence and 19 per cent told the researchers threats were made against family members.”

Looking at some the detailed examples in the research, the Herald article reported: “One MP said someone came to their office to try to stab them, while a different respondent said they were assaulted on the way to work. Another MP said their husband was physically attacked after someone launched at the politician in public.”

One of the article’s authors, forensic psychiatrist Justin Barry-Walsh, summarised it by saying, “I think that we’re showing that we do have a problem here” and, “You don’t have to be a political scientist to realise this is a troubling issue for our democracy.” He argued that the increasing toxicity in politics would drive people out of politics and weaken democracy and human rights.

Disenchantment with how politics works

As in the US and other parts of the world, increasing polarisation and toxicity in New Zealand is clearly related to growing anger and alienation with this country’s political and economic systems. And the reality is that if the public believe that politics and democracy have lost their integrity and now only work in favour of an elite, then they will be drawn towards political violence and other anti-political behaviour (such as non-voting or conspiracy theories).

The recent IPSOS survey results on rising populist attitudes in New Zealand indicate this. Published back in April, this survey should have sounded alarm bells for the state of New Zealand politics, as it indicated growing discontent and disenchantment with how democracy is working. For example, it was found that two-thirds of the country thinks that “New Zealand’s economy is rigged to advantage the rich and powerful” and that “New Zealand needs a strong leader to take the country back from the rich and powerful.”

The IPSOS survey results show the apparent existence of anti-Establishment and anti-elite beliefs. It seems that New Zealanders are very inclined to be angry at the country’s economic and political leaders, blaming them for the state of the nation. Political scientists refer to this with the term “populism”, which relates to both left-wing and right-wing opposition to elites. Although the discontent was found across all demographics, it was particularly pronounced amongst left-wing voters, those on low incomes, and Maori.

Declining social cohesion and equality

The extent to which New Zealand society is cohesive and trusting of each other also appears to be in decline, which can often lead to rising political violence. Survey results have also shown that New Zealanders believe divisiveness is increasing. The most important such survey was one conducted for the New Zealand Herald published in late 2022. It showed that 64 per cent of the public thought that New Zealand society is becoming more divided. Only 16 per cent thought NZ has been becoming more united in the last few years.

Most New Zealanders believe the unequal distribution of wealth is at the heart of this decline. According to the Herald’s survey, 74 per cent believed that wealth inequality is pushing us apart. In addition, when asked if “Our distribution of wealth is fair and good for the country,” 46 per cent disagreed, and only 24 per cent agreed.

Of course, much of this inequality then fuelled Covid-era discontent. The 2022 occupation of Parliament’s lawn, ending in fiery scenes and conflict, showed the horrific nature of this dynamic.

There is also a sense in which culture wars and identity politics are fuelling much of this anger. This is especially the case in the United States, where the big battles are increasingly not about economics or other traditional left-right concerns but about abortion, immigration, and race.

This article was originally published by the Democracy Project.