Table of Contents

As intended, my recent list of the Ten Best SF films sparked much debate (hey, we write only quality clickbait, here at the BFD). Like certain body parts, everyone has an opinion on the best SF films (and, as in some SF films, some people have plenty). The same goes in spades for horror.

Boy, oh boy: I thought narrowing down just ten SF films was tough! My shortlist was 25 movies long — and even that meant eliminating some classics of the genre.

Of course, some people don’t care for horror. “Why would you enjoy being scared?” someone once asked on my social media feed. Have they never been on a roller-coaster? But the best horror movies go beyond simple thrills: they reach deep into our psyches and pluck at the nerve-ends of our darkest fears.

For which reason, slasher films and torture-porn like the Saw and Friday the 13th franchises don’t feature high on my list, if at all. Pure gross-ness pales into insignificance beside the real dread of a good supernatural or cosmic horror tale.

Rich Evans of Red Letter Media caused some controversy, in their round-up of John Carpenter’s filmography, by rating Halloween square in the middle. He has a point: the film was genre-defining and a sensation in its time, but the passage of time has been less than kind to it. Similarly, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is actually far less bloody than people remember it.

Once, again, bear in mind that this is a purely subjective list, and the ranking is not entirely strict (just assume that the top 5 at least are all equally great).

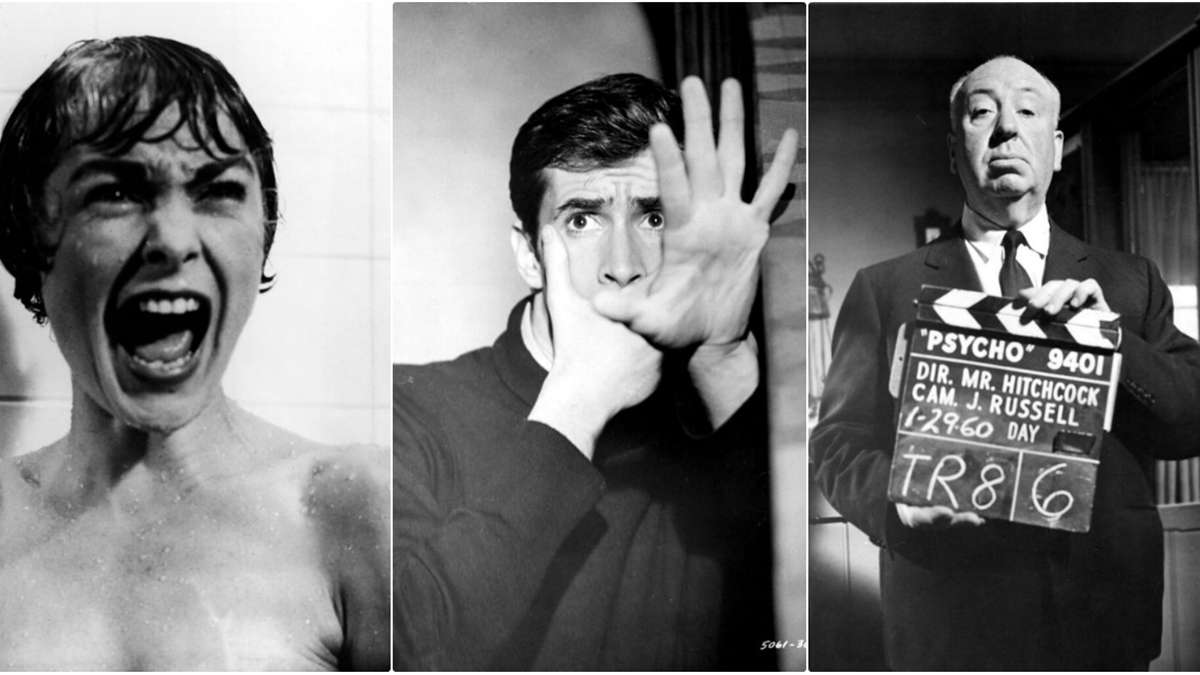

10. Psycho

Ranked relatively low solely because time has dulled its impact somewhat, but this is a masterclass in film-making. It’s forgotten, too, how much Psycho influenced the business of cinema: Hitchcock’s insistence on set showing times profoundly changed what had previously been a paradigm of screening continuous loops of newsreels and films (similarly, Jaws almost single-handedly created the “summer blockbuster”, when Spielberg insisted on its being released on cinemas across the country on the same day).

But everything about Psycho is near-perfect: from casting a handsome, boyish matinee idol and singer as the cross-dressing, mother-obsessed serial killer, to the pure power of suggestion in the iconic shower scene. Even lesser shots are a study in movie-making: observe, for instance, the stuffed owl, a harbinger of death, looming over Norman’s head in his earliest scenes. Norman’s final shot is still a chilling icon.

9. The Exorcist III

Although The Exorcist gets all the accolades and caused a sensation in its day (I remember even Australian news reports of people running screaming from the theatre), this long-neglected true sequel (let’s agree not to discuss Exorcist II: The Heretic) narrowly pips it as a better film.

Set 17 years after the first, the plot follows what were minor characters in the original, Detective Kinderman and Fr. Dyer, as they nurse a friendship built on their mutual memories of the horrors of 1973. When a series of murders match perfectly the (kept secret) modus operandi of a long-dead serial killer, Kinderman is forced to confront the nature of death, evil and the human soul.

George C. Scott is at his best as Kinderman, in a slow psychological burn, while also displaying his deadpan comedic chops in the brilliant “gefilte fish monologue”. Brad Dourif likewise delivers a bravura performance as the Gemini Killer.

The film suffered badly from studio cuts on its original release, and the modern cuts are a not-entirely-satisfying compromise, but it is still a much-undervalued classic.

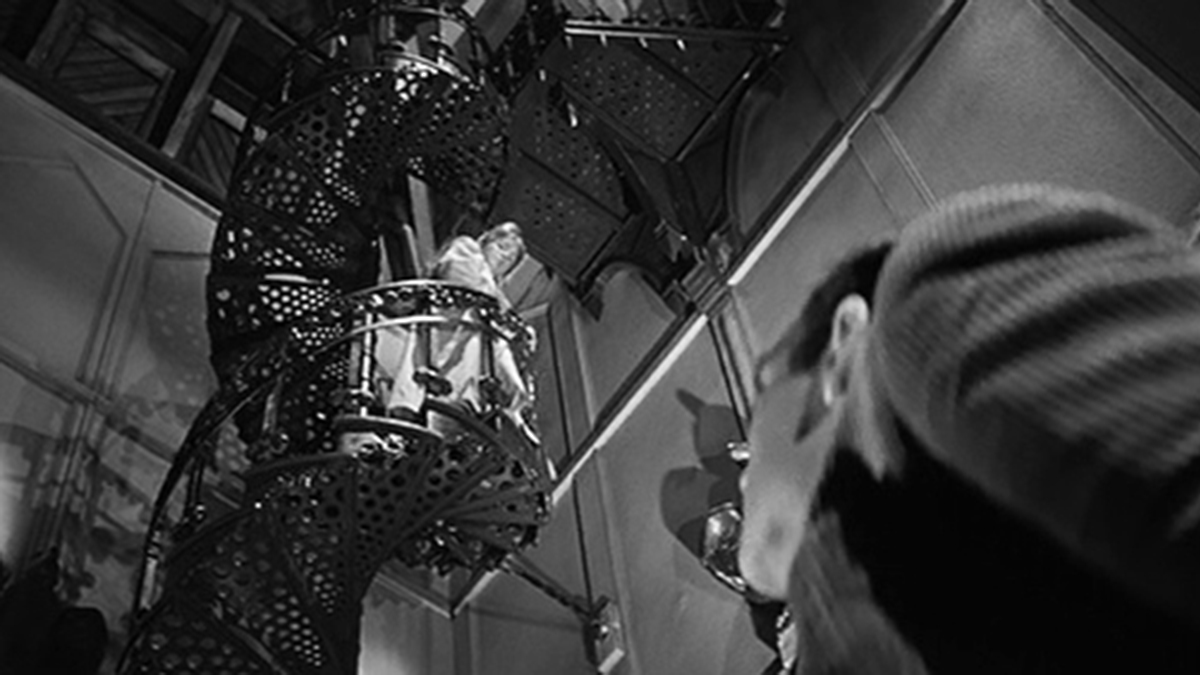

8. The Haunting

This film is but one of nearly a genre of its own based on Shirley Jackson’s classic gothic horror novel, The Haunting of Hill House. Along with the recent Netflix series, this is one of the best — and one of my favourite horror movies from a young age.

The film uses psychological horror and suggestion to create its atmosphere of claustrophobia and growing paranoia, as a team of paranormal investigators explore the secrets of the haunted Hill House. Shooting with anamorphic lenses and (monochrome) infra-red film creates a sense of unreality and claustrophobia, making the house itself the monster.

Disembodied voices giggle and weep, shadows morph and twist into ghastly montages. Daringly for its time, the film explicitly touches on sexual themes: lesbianism (even more remarkably, depicted positively), depravity, even bestiality. The house itself bends and distorts and exudes malevolence.

The 1973 Legend of Hell House was a worthy if lesser, remake. The less said about the 1999 version, the better.

7. 28 Days Later

Sure, George Romero single-handedly invented the modern zombie movie with Night of the Living Dead, but Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later took up the genre a notch, turning its zombies from shuffling automatons into terrifyingly fast, single-minded predators. More importantly, the zombies are very much second-order villains.

Instead, Boyle explores the monsters lurking in the souls of the living: from the scientists who create the “rage virus” and the activists who turn it loose, to the villainous Major West, played to perfection by Christopher Eccleston. West’s true evil though, is that he is not a cardboard villain, but his cold-blooded calculation. West epitomises the breakdown of civilisation, as the very men supposed to guard us while we sleep turn out to be very rough indeed. The zombies can’t help themselves: every bit as much as a death camp guard, West knows exactly what he is doing and that it is very wrong, but does it anyway.

6. The VVitch

The Witch (or “VVitch” to its fans) is not just a beautiful, haunting film, it’s practically a documentary of what a genuine, old-world witch scare must have been like.

The story reads like it is torn, verbatim, from the Malleus Mallificarum, and other contemporary accounts of the witch-craze. A 1630s New England farmer’s baby vanishes, apparently stolen and killed by an (unseen) witch. As their misfortunes pile up, the family become convinced, not only that they are persecuted by a witch, but that one of their own is part of the demonic coven.

Like Kubrick in Barry Lindon, director Robert Eggers used only natural lighting. But his pursuit of verisimilitude goes even further: the entire film is delivered in authentic 1600s idiom and thick, New England Puritan accents. At times, this makes it difficult for modern audiences to follow the dialogue but adds immeasurably to the film’s atmosphere of haunting realism.

Also highly recommended is Eggers’ The Lighthouse, a disturbing, surreal dive into the mouth of madness (bonus points if you get that one, too).

5. The Colour Out of Space

Many films have been made from the stories of horror master H. P. Lovecraft, and most of them are rubbish. But this adaptation of what Lovecraft regarded as one of his best stories is one of the most truly disturbing horror films.

In the remote New England backwoods, a meteorite crashes on the farm of the Gardner family, leaving behind a globule of the indescribable “colour” which then seemingly shrinks to nothing and vanishes. But then the horror begins. An unknown presence begins to blight the Gardner lands: crops grow abnormally large and abundant, but grotesque, foul-tasting and inedible. Bizarre, malformed animals are shot by hunters. The Gardner family one by one succumb to madness and grotesque bodily decay.

This is a film so good that not even Nicolas Cage could wreck it with his trademark histrionics.

In true Lovecraftian fashion, this is a story of creeping, cosmic horror and vague and formless dread, weird spatial distortions, creeping madness. It’s only in the third act that the direction throws restraint out the window and goes appropriately insane, as fitting Lovecraft’s vision of “a frightful messenger from unformed realms of infinity beyond all Nature as we know it”.

4. A Nightmare on Elm Street

Wes Craven has made many great horror films, from The Hills Have Eyes to The Serpent and the Rainbow, but Elm Street is deservedly his most iconic. It’s no wonder that Freddy Krueger has become a pop-culture icon: Craven purposely designed him to tweak our deepest fears. From his red-and-green sweater, colours chosen to literally jar our visual senses, to his “finger-knives”, designed to evoke our most primal fears of the talons of the creatures who hunted our ancestors, to his chosen victims — children, Freddy is meant to haunt our dreams.

It is the surreal, dream-imagery of Nightmare that is its greatest strength. Space and time are distorted, and the distinction between reality and dream becomes blurred to the point that its ending becomes a dream in itself. Craven’s literate background (he was an English and Humanities professor before turning to film-making) shines past the budget limitations of the film. From its imagery of Mother Mary-like body-bags and bleating lambs to quotations from Shakespeare, Elm Street is no mere low-budget shocker.

3. Suspiria

Am I talking of the 1977 original or the 2018 remake? Both — although Dario Argento’s original is perhaps the most striking, both are superlative, if almost diametric opposite films. Yet, both follow almost exactly the same story: an American ballet student arrives at a prestigious German dance academy — where, very obviously, nothing is as it seems. As young Suzy comes to realise that the school is really a front for a coven of witches, increasingly bloody mayhem ensues.

Argento’s film is the defining statement of the Italian Giallo genre: almost painfully saturated colours and blaring, prog-rock soundtrack. Luca Guadagigno’s remake pursues almost a complete opposite approach: 1970s, Cold War Berlin is grey and dreary, and Thom Yorke’s soundtrack is all muted piano, sighs and whispers.

Both are great films. Which you prefer depends, I suspect, on whether you prefer the brutal gore of knives stabbing still-beating hearts or the literally bone-crunching body-horror of dance-as-witchcraft.

2. The Shining

As with 2001 and SF, Stanley Kubrick’s contribution to almost any genre is bound to be among its best (ditto, war movies and both Paths to Glory and Full Metal Jacket). The Shining is no exception.

A writer and his family over-winter are caretakers at a remote, luxury mountain hotel. As the snows settle in, so does the cabin fever — or is it something more. Certainly, young Danny Torrance soon realises: gifted with psychic vision, he very quickly becomes aware that not all is as it should be. The Overlook Hotel, it turns out, has a violent and disturbing history, as does the film’s protagonist, father Jack.

Stephen King famously disliked Kubrick’s film, claiming that Kubrick had paid too little attention to the supernatural elements of the story. This might seem odd, given the ghostly goings-on, but King’s point is that, where he envisioned Jack as the victim of external forces, Kubrick’s Jack is the victim of his own inner demons as much as he is the ghosts of the Overlook. (Some pop psychology: King was famously unaware, at first, of the autobiographical elements of the recovering alcoholic writer character. His determination to make Jack the victim may hint at more personal motivation.)

Still, it’s a Kubrick film. Little more need be said than that.

1. The Thing

The only crossover on this list with the SF Top Ten, The Thing is far from the only great movie to span both genres, but it is one of the best of both.

As noted above, many films have been made from Lovecraft stories — nearly all of them badly. Ironically, perhaps, the best Lovecraftian movie is one not based at all on a Lovecraft story (although it shares certain affinities with stories such as At the Mountains of Madness). John Carpenter’s masterwork captures the nihilistic spirit of Lovecraft’s cosmic horror perfectly.

The crew of an isolated Antarctic base slowly become aware that an alien presence is amongst them — and the shapeshifting alien could be any one of them. Antarctica is as hostile and remote as deep space in this claustrophobic exploration of paranoia and horror. Rob Bottin’s special effects are still stunningly horrifying today: dogs mutate into slimy, bloody, three-headed monsters, stomachs turn into gaping, fanged maws and heads sprout legs and scuttle away. As one of the characters says: “You gotta be fucking kidding”. A brilliant cast, led by Kurt Russell, makes the film gut-wrenchingly real. Its bleak ending is one of the most nihilistic in cinema.

The movie was a flop on release but has gradually become recognised as not just a modern classic, but perhaps the best horror film.

So, that’s my attempt at a Top Ten Horror Movies. Here are some of the short-listed films that I reluctantly had to cut:

Frankenstein, The Ring/Ringu, Alien, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Evil Dead, Halloween, The Wicker Man, The Uninvited (1944), Videodrome.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD