Table of Contents

Jon Sanders

Jon Sanders is an economist and the director of the Center for Food, Power, and Life at the John Locke Foundation in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he also serves as research editor. The centre focuses on protecting and expanding freedom in the vital areas of agriculture, energy, and the environment.

You can fool all of the people some of the time; you can fool some of the people all of the time, but you can’t fool all the people all the time.” The fact that this quote is attributed either to Abraham Lincoln or P.T. Barnum perhaps testifies to its originator’s bona fides at fooling people.

Either way, the temporal element of the quote gets lost in discussing the respective magnitudes of those fooled. Nevertheless, in a practical application of it, the passage of time has resulted in the various governmental narratives regarding COVID having fallen apart. Except for a few hangers-on (the “some of the people all of the time”), most now acknowledge that lockdowns were a disaster; that school closures were never necessary and that they worsened educational outcomes and preexisting divides; that vaccine sceptics were justified and not monsters after all; and even that — as stated by the headline of a recent New York Times op-ed — “The Mask Mandates Did Nothing. Will Any Lessons Be Learned?”

It has been three years. Isn’t it about time we got more accurate data on COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths?

In the early weeks of the pandemic, many people wanting an accurate picture of the COVID’s scope sought out clear data. These people were not government health officials, but they had technical expertise in epidemiology, medicine, health, statistics, economics, child psychology, and many other fields — an illustration of the dispersed knowledge across society that Friedrich A. Hayek wrote about. Trusted with information as free citizens, they could get an accurate read on the situation and would even be able to explain it to others.

They were not trusted with information. Still, they knew enough to see that the official numbers were terribly muddied, so they probed on. Government officials and their media gatekeepers were discomfited and encouraged people and social media to “cancel” them and bury them with invective.

Among the muddied data were COVID hospitalizations and, consequently, deaths. Former AIER president Edward Peter Stringham wrote in July 2020 about what a Texas medical care facilities managing partner had told Alex Berenson (who later took Twitter to court for suspending him at the request of the Biden administration over his COVID questioning) about cases and hospitalizations. The partner said that “discharge planners are being pressured to put COVID as primary diagnosis — as that pays significantly better. … You open up your hospitals for normal medical care and you test everyone (sic) of those patients — the result is a higher percentage of patients who have COVID — now.”

As Stringham explained, “The hospitals are under financial pressure from having to mostly stop doing business for months, so they are classifying as many people as possible as a COVID case in order to gain the subsidy offered by the federal government.”

The federal CARES Act included a 20 per cent increase on Medicare reimbursement rates to hospitals for patients with a COVID-19 diagnostic code. So hospitals did have financial incentive to exaggerate the number of COVID hospitalizations and deaths.

The politicians and public health officials had their own incentives for the same — the higher numbers kept people in fear, and a fearful populace was surprisingly acquiescent to authoritarian acts hitherto unthinkable in peacetime: strict curfews, dress codes, shutting down entertainment districts, and requiring official papers to shop, dine, attend school, or travel.

But not everyone. Throughout the country, people were asking questions and hearing strange, jarring tales that nevertheless proved true. “COVID hospitalizations and deaths” also included gunshot victims, “intentional and unintentional injury, poisonings and other adverse events,” a “90-year-old man who fell and died from complications of a hip fracture,” “a 77-year-old woman who died of Parkinson’s disease,” more gunshot victims, even “a guy who was struck by lightning, fell off a roof, admitted to the hospital with serious injuries from the fall.”

These bizarre attributions were the absurd ends of the problem of “hospitalized with” or “hospitalized for” COVID that plagued researchers and questioning citizens curious about the scope of the problem. All that was known was that some people listed in the official data had been admitted to the hospital not on account of a dangerous COVID infection, which is what most people assumed the data meant, but for some other reason. But how many?

What proportion of COVID hospitalizations were “hospitalized with” vs. “hospitalized for”? We didn’t even know that.

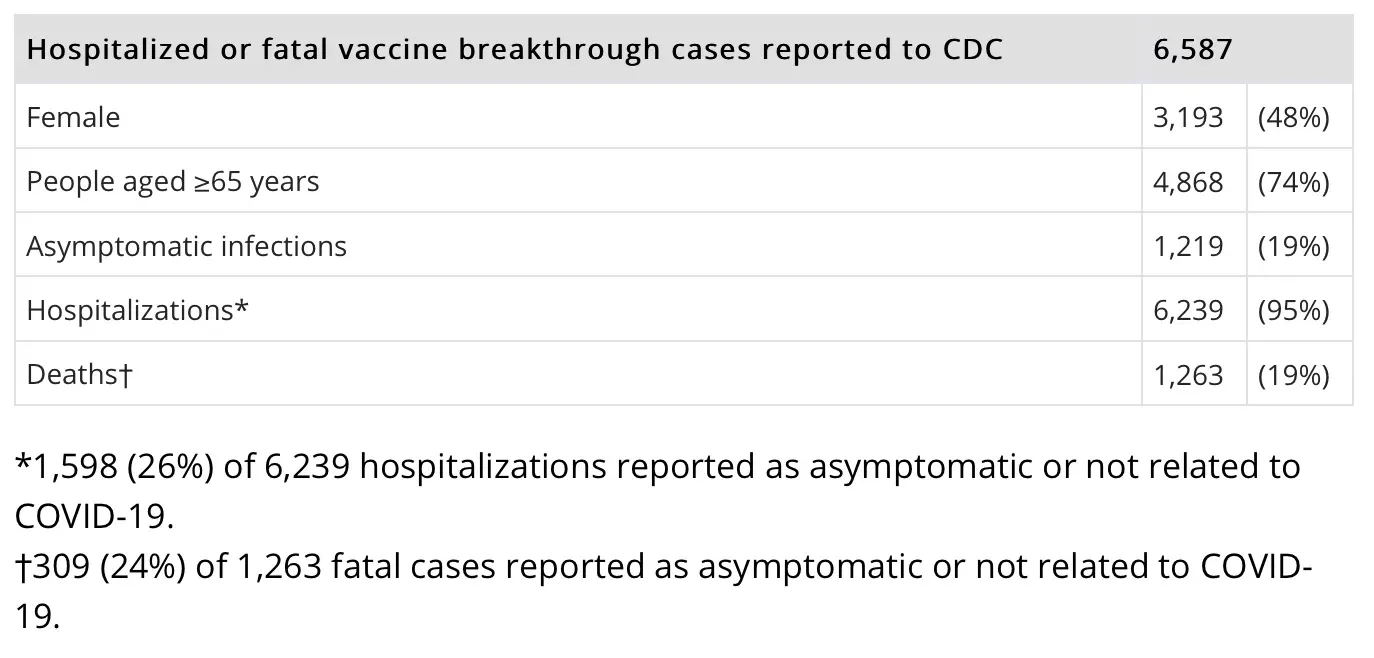

We would get the occasional glimpse that the proportion of “hospitalized with” could be quite large. On July 26, 2021, for example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report on “COVID-19 Vaccine Breakthrough Case Investigation and Reporting.” The report noted that 26 per cent of “breakthrough” (post-vaccination) COVID hospitalizations and 24 per cent of breakthrough COVID deaths were “asymptomatic or not related to COVID-19.” But it was only concerned with COVID hospitalizations and deaths for individuals who had received vaccination, not all of them.

Table from the July 26, 2021 CDC report on vaccine breakthrough cases

In September 2021, a preprint was released of a study examining Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitalizations related to COVID after vaccines became available. The study found that barely over half (52 per cent) of COVID patients in the VA were hospitalized for COVID, while the remainder were there for some other reason and incidentally found to be infected. Study authors made a cogent point about the question of “hospitalized with” vs. “for”: “If hospitalizations are used as a metric for policy decision-making, patients hospitalized for the management of COVID-19 disease should be distinguished from patients who are hospitalized and incidentally found to be infected with SARS-CoV-2.”

Some areas did begin tracking the difference, including New York (57 per cent “for” at the time of publication), Ontario (54 per cent), and Massachusetts (30 per cent).

On January 13, CNN medical correspondent Leana Wen publicly called for accurate accounting of COVID hospitalizations and deaths. In a Washington Post column, Wen highlighted data from Massachusetts showing that “only about 30 per cent of total hospitalizations with COVID were primarily attributed to the virus” and discussed the problems from overcounting COVID hospitalizations.

The following day, CNN anchors questioned her assertions, with Poppy Harlow asking if she had “thought about” whether her information might “give fodder to conspiracy theorists and those who downplay COVID, to anti-vaxxers.” Wen, to her credit, noted that others’ criticism was that “You should have said this two-and-a-half years ago.” Wen said, “I think at the end of the day we just need the truth.”

On that count, Wen is right. We just need the truth.