Table of Contents

Dr Melissa Derby

Senior Lecturer at The University of Waikato

This article was first published by The Common Room

What is the purpose of education? It’s a question we should be seriously asking in New Zealand. Recent reports about the dire state of our literacy and numeracy outcomes have led, incredibly, to questions about how relevant these foundational and crucial aspects of education are. While some view education as solely about learning literacy and numeracy skills, others think education should develop children’s social and emotional competencies or validate various socially-approved aspects of their identity.

So what are some of the different views on the purpose of education, and what might adopting or discarding these ideas mean for the education of New Zealand children? Martin Luther King, Jr. suggested that the first function of education is to teach learners to think intensively. A reporter conducting research in a Los Angeles high school in the mid-1980s argued that “A human being who has not been taught to think clearly is a danger in a free society”.

Similarly, John F. Kennedy noted the relationship between the ability to think critically about civic affairs and the strength of a democracy. King went one step further and added that education should also support moral development. “Education without morals”, King argued, “is like a ship without a compass, merely wandering nowhere. It is not enough to have the power of concentration, but we must have worthy objectives upon which to concentrate.”

The topic of morality is difficult to untangle, and with so many things said to comprise morality in the 21st century, it is unlikely that a consensus can be reached anymore. That doesn’t stop many schools delving into areas that impact on morality with gusto! However, is morality an area schools should be wading into though? Are teachers equipped to do so? And what role do families play in moral instruction?

Back to King, who hoped that education would “teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character – that is the goal of true education.” Perhaps the jury is still out on what sorts of characters our current system is producing.

John Dewey and Carl Rogers argued that education should be relevant. While it is hard to conceive why anyone would wish it to be irrelevant, Dewey, Rogers and others believed that no one should ever have to learn something they think is irrelevant. These ideas have supported the rise of ‘child-led learning’ and student choice about what one might (or might not) learn. How, though, does a child determine what is or isn’t relevant, when that child has little or no knowledge of the material to be learned, nor any experience of how that material might apply in their future?

For example, can a young child in kindergarten, who is just learning the alphabet, truly appreciate how valuable it is to learn those symbols in their arbitrary order, and the lifelong access to a range of skills learning the alphabet will afford? Does the child learn the alphabet because they think it’s relevant, or do they learn the alphabet because they are told to by adults who know how important it is to learn it?

The argument about education being relevant has spread, most notably in relation to ethnicity. While it is important to recognise different cultural knowledge, experiences, and worldviews, such thinking has led, for example, to classical music programmes being cancelled for Pacific children, because classical music is not relevant to Pacific children. Classical music may not be part of a traditional Pacific musical heritage, but we must ask: “Should education open doors to a wider world, or should it paint a child into his or her own little corner?.”

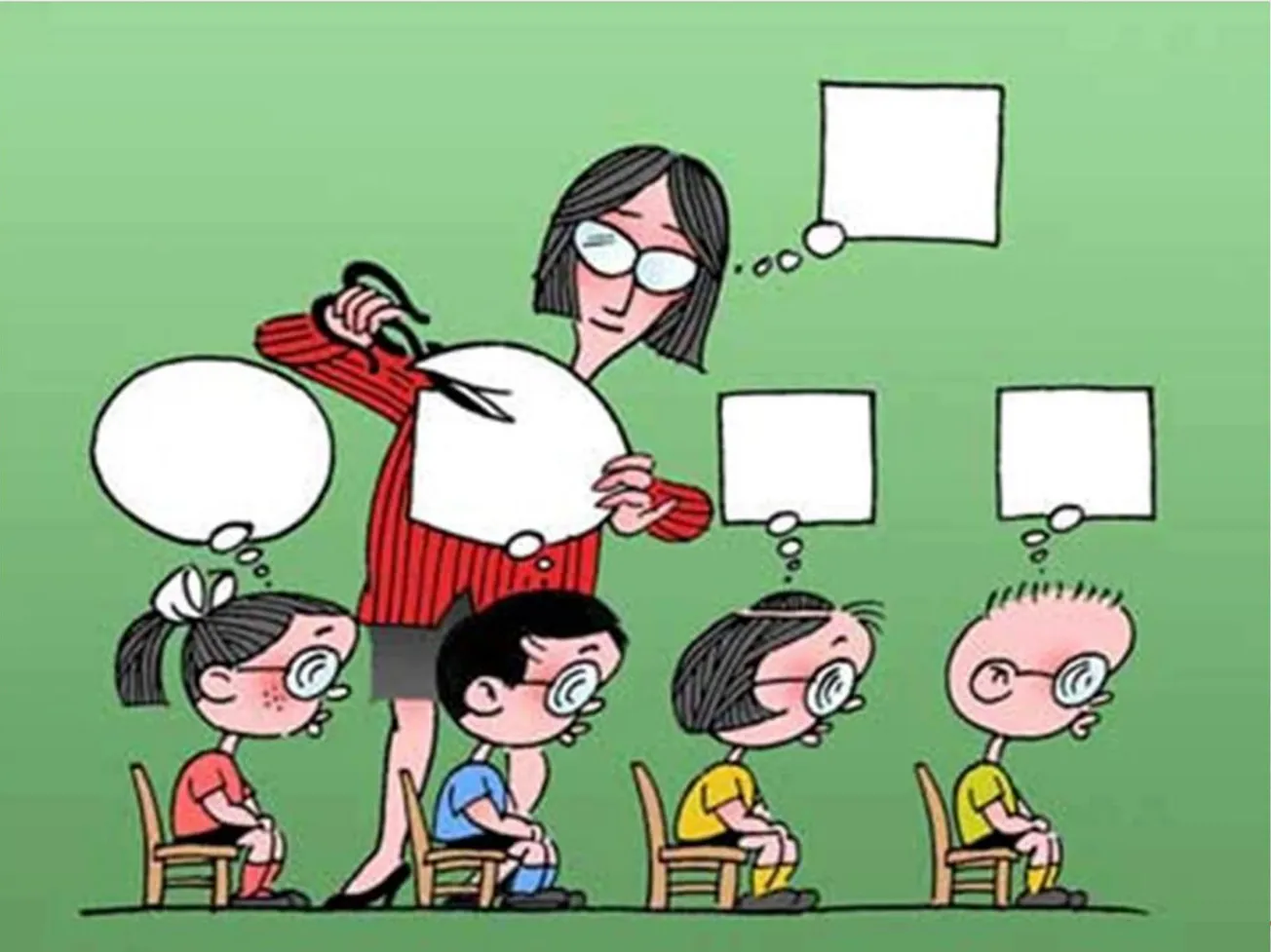

Throughout history, schools have been used to bring about social change. The general idea is teachers aren’t there just to transmit knowledge to students, but rather to condition students to want a different kind of society. Examples of this in the 21st century are rife, with even primary school children taking (or receiving) a view on things like capitalism and climate change. In many cases, these are complex issues that the most intelligent in our society have yet to wholly understand. Thomas Sowell argued that teaching such things to children is like telling people how to perform surgery when they don’t understand the basics of anatomy or hygiene. While it is important for children to engage in current affairs and issues that affect society, perhaps we need to ensure we get the basics right first so that they can properly engage with these issues. Sowell also argued that education should give students intellectual tools like literacy and numeracy, and teach them to analyse and reach conclusions based on logic and evidence. That would seem to me to be a good place to start (together with ensuring children actually attend school). This approach would help to improve the terrible outcomes that too many New Zealand children are experiencing.

Those who are shifting the focus away from the basics of education pay no price for being wrong. Rather, that price is paid by those children who rely on a good education to improve their lot in life. In other words, the price is paid by those who can least afford to pay it. For that reason alone, we owe it to New Zealand children to be firm about the purpose of education, and that’s to provide, at the most basic level, children with strong literacy and numeracy skills, and the ability to actually think.