Table of Contents

For many modern folk, not just tree-hugging vegans, the very name ‘industrialised agriculture’ is practically a swear word. Like so many popular nostrums around the environment, it’s a completely skew-whiff conception.

While ‘industrialised agriculture’ by its very name conjures up images of Dickensian squalor, the fact is that industrialised agriculture is not only desperately needed to feed the global population, it is, contrary to popular imagination, much better for the environment. Large-scale industrial agriculture has, in recent decades, produced so much more food, using far less land, that many countries are actively ‘re-wilding’ – returning previously farmed land back to nature.

As for animal welfare, it’s instructive to look back a few centuries. Many moderns would be shocked to see just how radically different the reality of pre-industrial farming was, in contrast to their romantic notions.

The unenviable lot of cattle is a case in point.

In the 17th century, it was actually illegal to sell ‘unbaited beef’. That is – beef had to be sourced from bulls who were literally tortured to death.

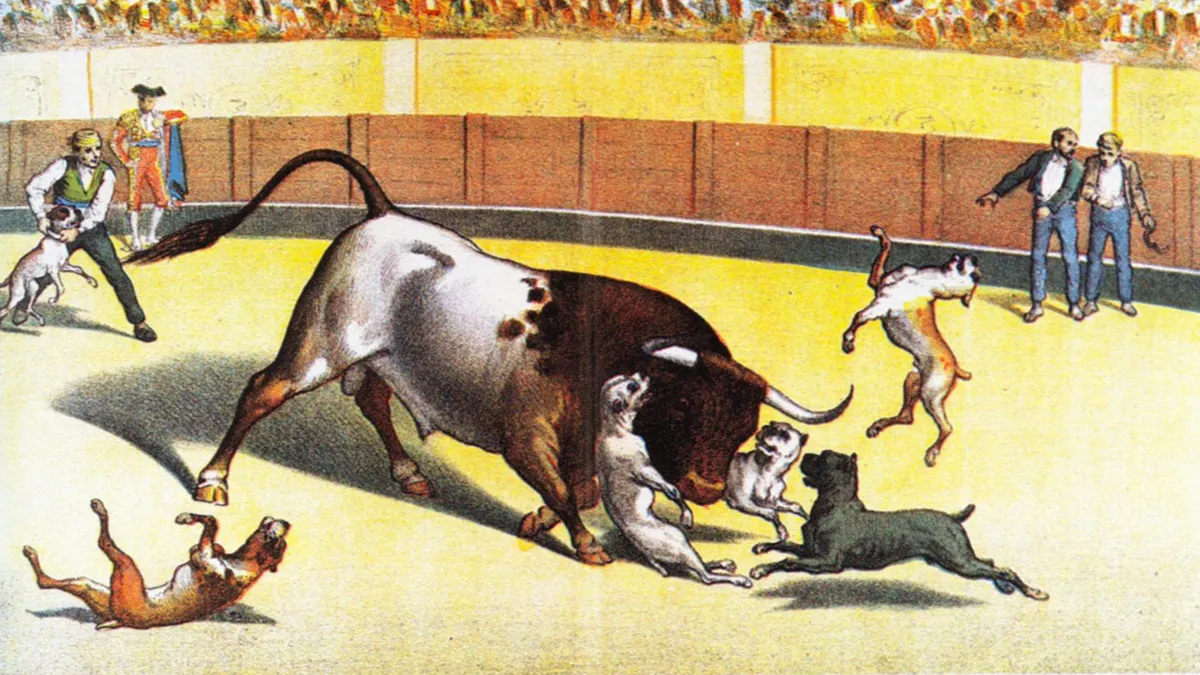

[‘Baited beef’] came from an animal that spent its last moments alive being tortured. An excited crowd would gather to witness the “baiting,” or the releasing of dogs to attack the bull and induce a state of panic. The dogs were trained to bite the bulls’ necks and faces, especially the mouth and nose. The bull was typically trapped in a small, enclosed space or chained to an iron stake to prevent escape.

If it sounds bad for the bulls, the dogs also suffered unspeakable cruelty.

Special dogs, from which the modern bulldog and pit bull derive their names, were bred for the task: to keep their jaws clenched into the flesh of a bull even as the bull ripped out the attacking canine’s entrails.

After a dog latched onto a bull with its teeth, the dog breeders would sometimes hack off the dog’s feet to test the canine’s toughness.

This was not only what passed for entertainment, it was a way for dog-breeders to fetch a premium for their animals. “A bulldog that would quit after its feet were chopped was disposed of and not used for breeding,” as one contemporary noted.

The practice went on well into the 19th century.

What was the point of tormenting bulls and dogs in this manner, let alone legally requiring that bulls spend their last moments of life this way before becoming sellable beef? While the blood sport provided entertainment, baiting was also thought to produce higher-quality meat. Dying in battle meant that the bulls’ muscles worked hard until the final moment. This was thought to tenderize the meat and, inexplicably, to improve the beef’s nutritional quality.

Compare that with the premium beef farmed in today’s ‘less natural’ industry.

Today, in contrast, people consider the highest-quality beef to be that of certain Japanese cattle that live in a stress-free environment with daily massages to work out muscle tension and even soothing classical music. And most farmers now go to great lengths to ensure cattle’s final moments are calm, using a carefully designed system.

Cows had it little better than bulls.

Before the development of railways, it was difficult to transport milk from the countryside into cities without it spoiling first. As a result, many dairy cows were kept inside cities, decreasing milk transport times but often resulting in appalling conditions for the animals. Cockayne wrote this of London’s urban cows: “With a small and diminishing number of grazing opportunities and little space to store fodder, beasts were left to wallow in their own excrement, tied in dark hovels, where they fed on brewers’ waste and rank hay. Their milk was known as ‘blue milk,’ and was only good for cooking.” The already poor quality of the unhappy creatures’ milk was further diminished when the substance was taken into the marketplace through the city’s squalid streets. Consider the following description of milk in London from a work published in 1771:

‘The produce of faded cabbage leaves and sour draff, lowered with hot water, frothed with bruised snails, carried through the streets in open pails, exposed to foul rinsings discharged from doors and windows, spittle, snot, and tobacco-quids from foot-passengers, overflowings from mud-carts, spatterings from coach-wheels, dirt and trash chucked into it by roguish boys for the joke’s sake, the spewing of infants who have slabbered in the tin measure, which is thrown back in that condition among the milk, for the benefit of the next customer; and, finally, the vermin that drops from the rags of the nasty drab that vends this precious mixture.’

Ah, the ‘good old days’. Makes ‘industrialised agriculture’ look pretty special by comparison, doesn’t it?