Table of Contents

Matua Kahurangi

Just a bloke sharing thoughts on New Zealand and the world beyond. No fluff, just honest takes.

Twelve months ago, few New Zealanders had heard of Eru Kapa-Kingi. Now, he is suddenly everywhere. He made headlines last week for publicly challenging ACT Party leader David Seymour to a fight, in response to Seymour allegedly calling his mother, Te Pāti Māori MP Mariameno Kapa-Kingi, an “idiot”. The reaction was theatrical, if not juvenile. For someone being positioned as a thoughtful legal academic, it was surprising.

That challenge to Seymour, delivered with all the subtlety of a schoolyard dare, was only the latest in a series of calculated public moments that have catapulted Kapa-Kingi into the spotlight. But his rise has not been organic. It has been staged, rehearsed and very likely orchestrated by the party machinery around him.

Eru Kapa-Kingi was born in 1996, raised in Whangārei, and is one of triplets. He studied law at Victoria University of Wellington and graduated with first-class honours. That sort of academic success is commendable. However, in certain circles and institutions, being Māori will always open doors that remain shut to others. Victoria University, with its known left-leaning, is no stranger to that.

As a teenager, Kapa-Kingi gave a TEDx talk on youth suicide in Northland, speaking with empathy and clarity about his work with the RAiD Movement, a youth-led mental health group. It was a strong start. But somewhere between the lecture halls and protest rallies, the youth advocate transformed into something else entirely.

By mid-2024, Kapa-Kingi appeared on TVNZ’s M9 series with a speech titled “Unravelling the colonial theory of law”. TVNZ described him as a legal academic and a staunch advocate for Māori rights and sovereignty. The programme gave him a national platform to promote his views on jurisprudence and Te Tiriti. For someone relatively unknown in the broader legal world, it was a high-profile endorsement from the state broadcaster. One could be forgiven for wondering whether it was a coincidence that this public profile boost came just months before a major protest campaign, led by the very same individual.

That campaign was, of course, the Toitu Te Tiriti hīkoi, organised in response to the government’s Treaty Principles Bill. In November 2024, Kapa-Kingi appeared fresh-faced on The Hui alongside veteran activist Hone Harawira, outlining plans for the march. He wore polished jewellery, including solid gold earrings, a gold necklace and pendant, and presented himself as a charismatic, educated young Māori leader.

But within days, that image changed dramatically. Gone were the gold chains. Kapa-Kingi now wore oilskin jackets, dirt-scuffed Red Band gumboots, and a greenstone hei tiki. He had acquired a full facial moko and seemed to have adopted the wardrobe of a rural farmer overnight. It came across as a calculated wardrobe shift, crafted to make him look like a humble, hardworking Māori from Ahipara, tending to the whenua and living a life of quiet struggle.

That level of transformation was more than symbolic. It was strategic. Political image-making is nothing new, but when it is done this quickly and obviously, it raises questions about sincerity. The timing was suspiciously perfect. The shift came just in time for the national rollout of the hīkoi, which gained enormous attention from mainstream media. Sceptics could be forgiven for thinking it was part of a larger marketing plan.

And indeed, it was.

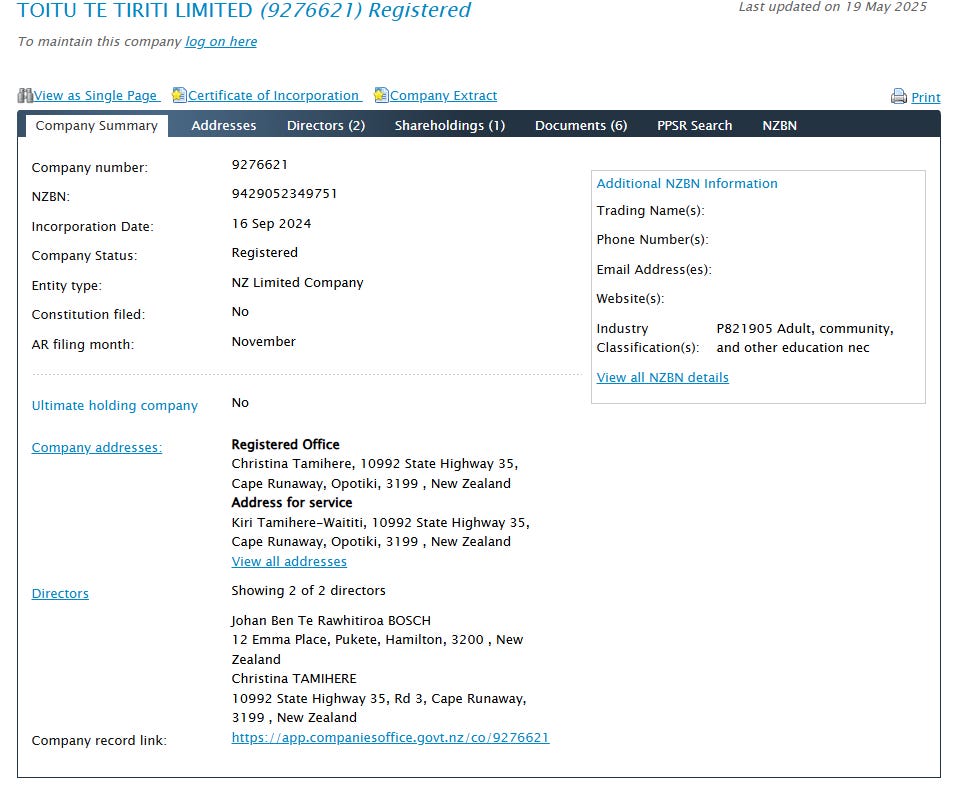

Toitu Te Tiriti, the protest campaign Kapa-Kingi fronted, was presented as a spontaneous, grassroots uprising. In reality, it was anything but. The company behind it is directed by Christine Tamihere, wife of Te Pāti Māori co-leader Rawiri Waititi. The protest was backed openly by the party, with leaders like Waititi and Debbie Ngarewa-Packer giving it their full endorsement on social media. Kapa-Kingi, son of a party MP, did not just show up and volunteer to lead. He was placed there, likely with careful instruction and support.

This movement was not built in marae kitchens or community halls. It was built in meetings, strategy rooms, and PR planning sessions. It was carefully timed and expertly executed. The media, whether wittingly or not, played their part perfectly. They published the protest schedule, location details, and live updates. It was free advertising for Te Pāti Māori on an unprecedented scale.

The great irony is that the protest was not even necessary. Prime Minister Christopher Luxon had already announced the government would not support the Treaty Principles Bill beyond its second reading. That decision was firm, public and repeated. The threat was neutralised before the first protester hit the road. And yet, the march carried on, full of urgency and outrage, as if nothing had changed.

Why? Because the protest was never really about the bill. It was about visibility. It was about political branding. It was about building momentum for Te Pāti Māori and for the new public face of their kaupapa: Eru Kapa-Kingi.

This article was originally published on the author’s Substack.