Table of Contents

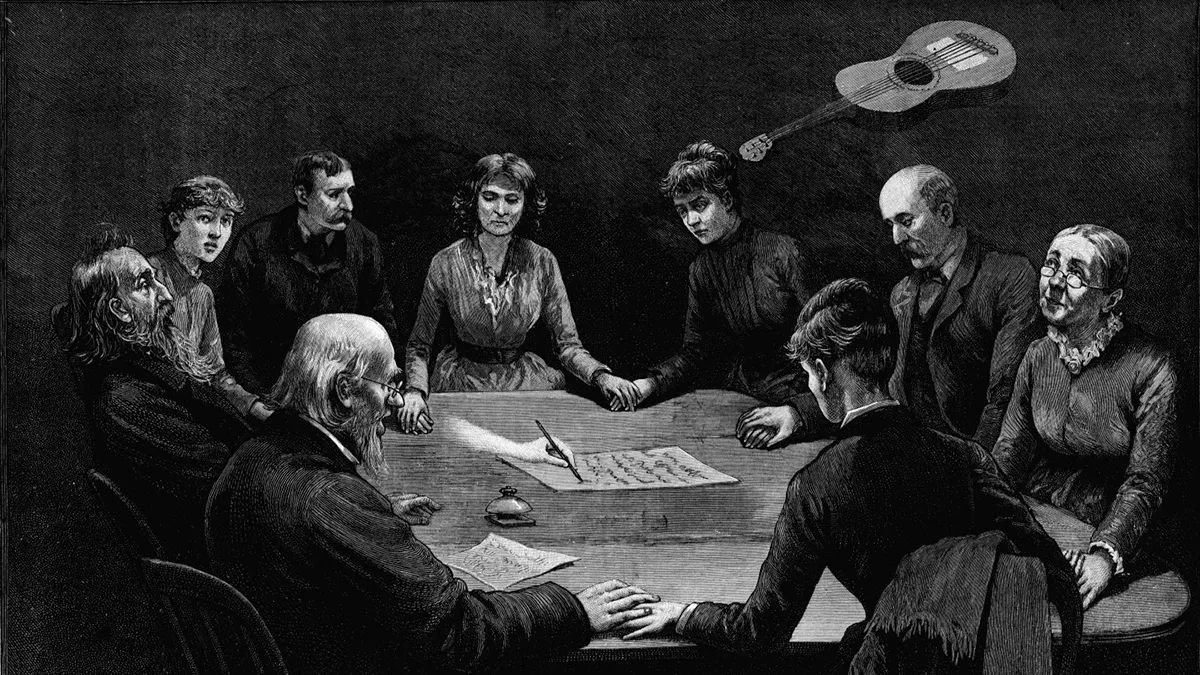

When we think of Spiritualism, we tend to think of seances with middle-class women in Victorian London, or the grief-stricken generation of the 1920s. Well-dressed middle-class people gathered in a darkened drawing-room. Table-rapping, Ouija boards and so on.

In fact, Spiritualism began in the mid-19th century United States and led to a radical political and social movement. Abolitionism, female emancipation, clothing and medical reform, even free love. Anti-organised religion and radical socialism. Spiritualism had it all – and women were at its forefront.

The roots of Spiritualism began with the 18th Christian-scientific mysticism of Emanuel Swedenborg, and the ideas of Franz Mesmer. Swedenborg believed that, following physical death, the soul entered a rebirth into the world of the spirits – evolving and growing, achieving higher and higher states of heaven. Mesmer, at the same time, claimed to discover a vast field pervading all things (think of Star Wars’ ‘the Force’), which he called ‘animal magnetism’.

Experimenters with ‘Mesmerism’, or hypnosis, found that entranced patients seemed to be able to tap into vast wells of wisdom that they couldn’t in a conscious state. Which was in itself a radical new interpretation of Christianity, which had traditionally envisioned the afterlife as a kind of eternal choir. This offered tremendous comfort to the bereaved, knowing that the dead were not just in a realm of bliss and wisdom, but continued to grow. This was particularly powerful in an age when infant mortality was ever-present: even deceased infants were nursed to a spiritual childhood and wise adulthood. In tandem, the idea grew that suitably mesmerised living beings might be able to commune with the greatly enlightened spirits of the dead.

It was in the ‘Burned-Over District’ of the US, that an otherwise uneducated cobbler name Andrew Jackson Davis published, in 1847, The Principles of Nature, Her Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind. Incidentally, the ‘Burned-Over District’ has been a religious focal point almost as intense as the ancient Middle East, producing such people and movements as Joseph Smith, the Seventh Day Adventists, the Shakers and more.

At first, Jackson’s book seemed doomed to obscurity. But in 1848, the three Fox sisters – Leah, Margaretta and Katherine – claimed to have made contact with the spirit of a peddler who had been murdered and buried beneath their home. When the Fox sisters’ mediumistic performances reached the home of Quakers Isaac and Amy Post, Spiritualism as a new religious movement was born.

The Posts were radical Quakers committed to a deep commitment that the inward light of God was truly revealed to each and every individual person and [this…] committed them to the cause of the abolition of slavery and to the equal rights of women. Their home was a stop on the Underground Railroad. They just didn’t talk about it, they were about it. And the who’s who of Civil Right activists of that time were regular speakers in their home including people like William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, Susan B Anthony, Sojourner Truth and numerous others.

Spiritualism wasn’t just to have any cradle, but was born and nursed among some of the most religiously heterodox and socially radical circles of the day. Spiritualism wouldn’t just seek to bridge the world of the living with the world of the spirits, it would seek to transform this world in a truly revolutionary sense.

What had begun as ghostly rappings from an alleged murdered peddler was to become a revolutionary religion bent on total social transformation.

Spiritualism not only appealed to such religiously motivated radicalism, but to American commonsense empiricism: the ‘I’ll believe it when I see it’ attitude.

That the Spiritualist mediums were women was another decisive factor. The position of women in mid-19th century American life, particularly religious life, was one of silence and obedience: she was fundamentally passive to the teachings of the preacher or priest and fundamentally passive to the dictates of her father and then her husband. So, when these women began eloquently expounding, at great length, on religious matters, well, it just had to be the spirits talking.

I mean these were just simple women: how could they know all of these things? And further how could they form opinions about religious matters and social issues? It must be Supernatural.

And the spirits of the dead speaking through these women were naturally far ahead of we earthbound mortals in everything from social and moral wisdom, to technology and medicine.

That is was the spirits speaking, rather than the lowly women themselves – who were just, as women were, mere vessels – made it easier for male audiences to accept. So, suddenly, women and girls who:

Had previously had no real social presence were now taking the stage the pulpit in the podium before audiences of hundreds and thousands, and speaking, lecturing even, precisely because it wasn’t the voice of the girl or woman that spoke but the spirits. The men safely protected from a woman speaking by the trance state.

But again what the spirits had to say, indeed to lecture the living about, was surprising shocking and revolutionary. Women and girls spoke eloquently for hours in trance about metaphysics, science, medicine, religion, but most alarming of all about social reform. Consistently from the voices of the spirits came calls for the abolition of slavery, children’s rights, labor reform and the reform, if not the complete abolition, of marriage in lieu of free love. Dress reform for women, universal emancipation and suffrage, vegetarianism, temperance, medical reform. A deep sentiment against organized religion of any kind, including Christianity. Of course radical individualism and freedom of conscience and religious matters. Motherhood as a woman’s choice and – I think perhaps most radical of all – utopian socialism.

It was one thing to dismiss such talk as the witless mouthing-off of the ignorant lower-class rabble, or silly women’s talk – but now it was coming from no less an authority than the spirit world.

It's difficult to imagine how quickly, from 1848 with the first rappings in New York, to the Civil War in 1861, the public imagination would be transformed by women taking the historical and literal stage and urging forward a social agenda that in many ways is more radical than anything that’s been hitherto accomplished in the vast revolutions of even the 20th century.

Even from the beginning, though, Spiritualism was continually plagued with admissions that it was all a massive fraud. The Fox sisters eventually confessed that the rapping were just popping their ankle joints and bouncing apples attached to the strings underneath their skirts. In the 1920s, the great celebrity of the day, Harry Houdini, relentlessly debunked fraudulent Spiritualists. So, over time, Spiritualism became the vaguely comic mainstay of horror movies and youngsters playing with Ouija boards (which, it is often forgotten, originated explicitly as a silly, fun children’s toy).

But, for a decade or so in the late 19th century, Spiritualism was a genuinely transformative, radical social and religious movement.