Table of Contents

In modern times, the world capitals of fashion are almost all in Europe: Milan, Paris, London. As it turns out, Europe as the hub of world fashion is not exactly new. Five thousand years ago, the fashion capital of the prehistoric world was also in Europe – at a site in southern Spain that has produced the largest concentration of neolithic upmarket fashion goods ever found.

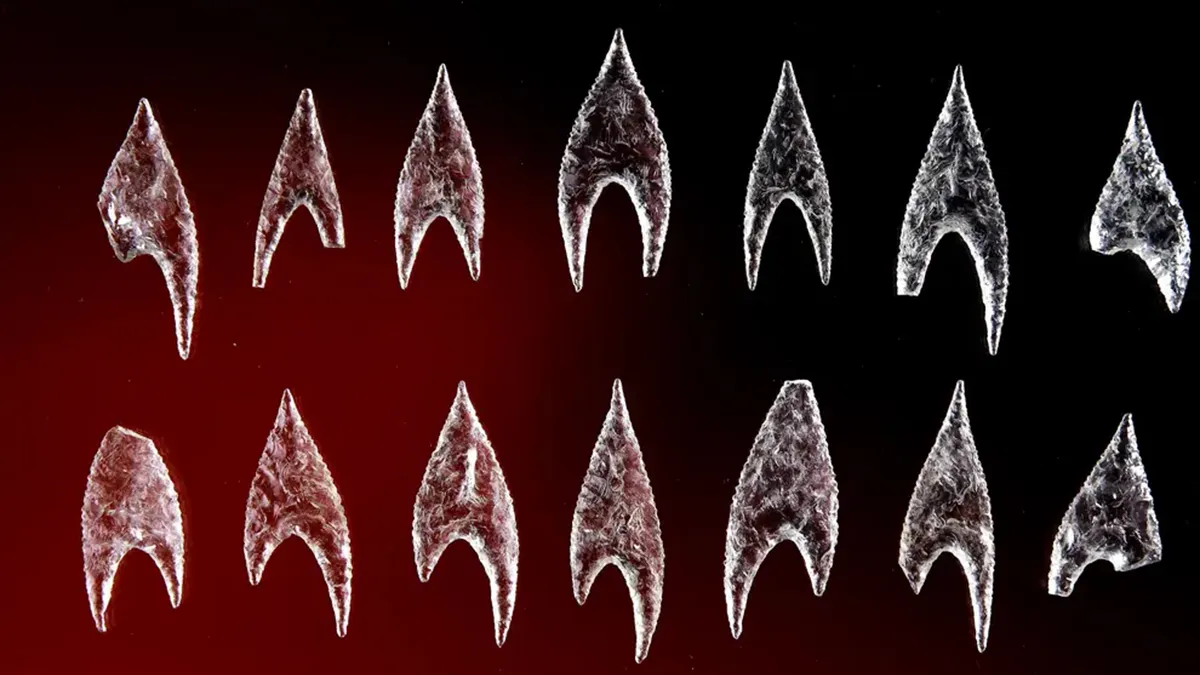

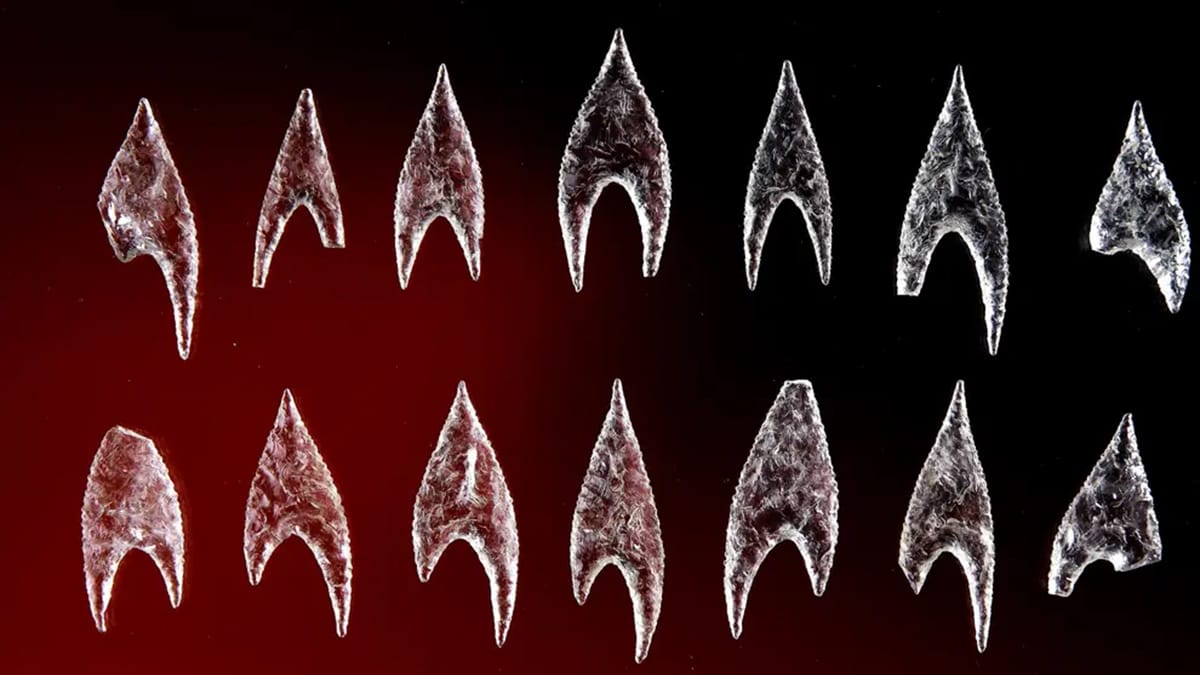

With only the barest fraction so far excavated, archaeologists have found hundreds of spectacular gold, ivory, rock-crystal, amber, greenstone, sea-shell, ostrich eggshell, flint and copper artefacts.

The site is located near Seville, between the towns of Castilleja de Guzman and Valencina de la Concepcion.

Excavations over the past 20 years suggest that the site was a major international trade centre, attracting goods from thousands of kilometres away. Testing shows that the raw materials for the must-have prehistoric accessories came from as far away as Western Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Sicily.

So far, archaeologists – from the Spanish universities of Seville and Huelva and from Germany – have found dozens of deeply buried complete and fragmentary ivory figurines, drinking cups and ornamental combs, as well as jewellery and luxury furniture and garment decorations.

Most of the ivory is from African elephants – but some are from Asian ones, which at that time still roamed the grasslands of western Asia. Archaeologists and other scientists from five UK universities and other research institutions have helped date and analyse many of the key finds.

Gold – probably from southwest Spain – was used to produce eye-shaped solar religious symbols made of gold foil. The site has so far yielded two of these highly prized artefacts, the only ones ever found in Western Europe.

Only Good News Daily

As an international trading hub, the site was a magnet for people as well as goods. Tests on skeletons buried at the site indicate that around 33 per cent were ‘non-local’, although whether they were from other parts of Spain, or further away, has yet to be established. Still, at around the same time as the massive standing stones at Stonehenge were being raised, the site was a settlement of a population of up to several thousand.

Ancient finds like these show that globalisation is far from a recent phenomenon. For tens of thousands of years, humans have been trading goods over vast distances. The Australian Aborigines traded sought-after items such as stone axes and ochre for ceremonial painting, passing the valuable items from group to group over thousands of kilometres. In more recent times, glass beads from Venice were being traded in Alaska even before Columbus sailed the ocean blue.

Long before that, though, one of the most famous artefacts in ancient human history involved trade over hundreds of kilometres.

One of the earliest examples of a figurative sculpture in history, the Venus of Willendorf depicts “a symbolised adult and faceless female with exaggerated genitalia, pronounced haunches, a protruding belly, heavy breasts and a sophisticated headdress or hairdo”, according to researchers.

As its name suggests, the Venus was found in the Austrian village of Willendorf in 1908. But the statuette is carved from a type of limestone that is not found in the area. So, where did it come from?

To determine Venus of Willendorf’s origins, researchers turned to modern technology. A team of scientists led by Gerhard Weber, the head of the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology at the University of Vienna, used high-resolution tomographic scans to take a close look at the sediment and particles that make up the statue.

By comparing these scans to other sediment samples – sourced from “France to eastern Ukraine, from Germany to Sicily”, according to a statement from the University of Vienna – Weber and his team were able to zero in on the Venus of Willendorf’s origins.

As they described in a study published in Scientific Report, the researchers found that the Venus of Willendorf’s oolite limestone was “virtually indistinguishable” from limestone found near Lake Garda in Italy.

All That’s Interesting

At that time, the Alps were covered in glaciers, so its journey from Italy to Austria would have had to be a roundabout one.

Even more interesting, similar figures, though much younger, have been found in southern Russia. Genetic results show that people in Central and Eastern Europe were not connected at the time. So, perhaps like the goods traded in ancient Australia, the raw materials and probably the finished carvings were traded from one group to another, over thousands of kilometres.