Table of Contents

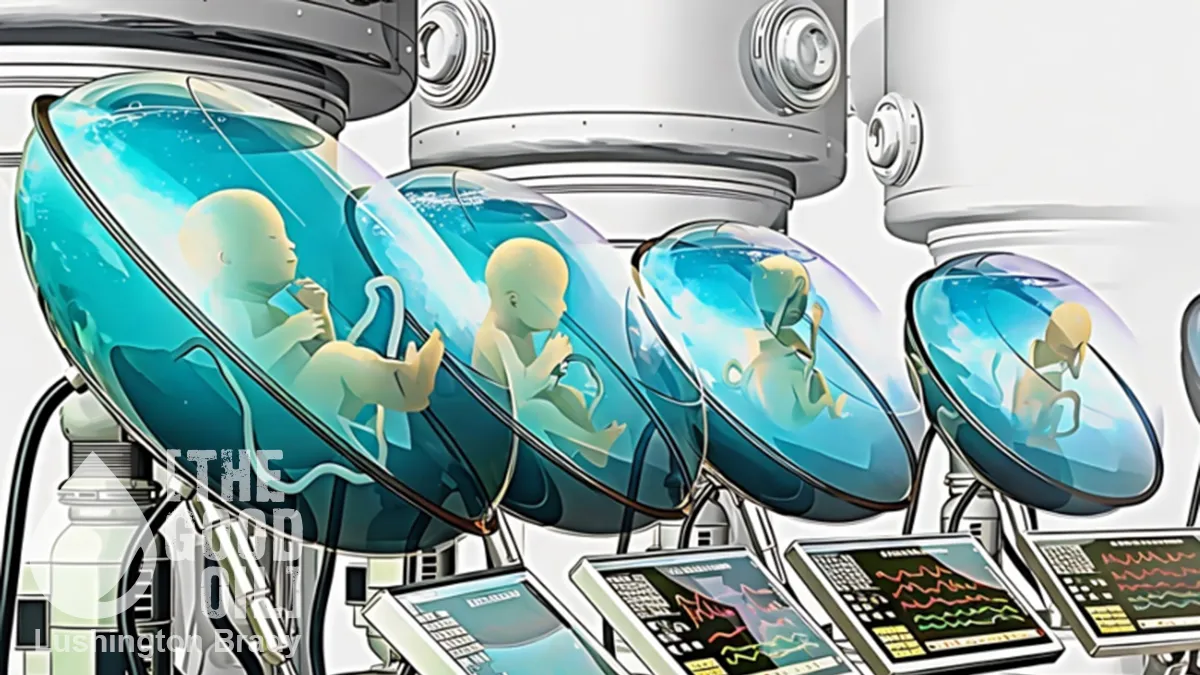

As I’ve written several times lately, the Western world for the past few decades has been gaslit into one of the most grotesque social experiments in human history. That experiment is universal, early-age childcare.

Apart from the brutal communist regimes, no human society that I can think of has ever done this. Even the insanely militaristic Spartans waited until children were seven before taking them from their families. The Maoists forced mothers at gunpoint to surrender their babies to the collective creches so they could be ‘liberated’ to toil from dawn til dusk in the collective farms.

In the West, mothers were gaslit into surrendering their babies to total strangers, so they could be ‘liberated’ to toil in soulless cubicle farms.

At almost no point has anyone stopped to seriously ask, ‘What the hell are we doing?’ The few people who dared to ask were bullied and lied to.

When it comes to young children in childcare, the effects on those children are often ignored or are (mis) portrayed as overwhelmingly positive. In any case, the central concerns of studies are the impact on mothers and the boost to the economy.

What if it turns out that long daycare is actually harmful to many children and that the consequences will play out for the rest of their lives?

We know perfectly well that recent generations are very different from those who came before. Childhood mental health is in catastrophic decline, school grades are steadily declining and more and more children are becoming lifelong dependents of the National Disability Insurance Scheme, among many other factors ‘trending downward’, as the bureaucrats like to say.

Is the pervasiveness of early childcare more than just a coincidental correlation?

The advocates and beneficiaries of the childcare industry, no doubt, would bristle at the suggestion that childcare could damage our young ones. We need only to see how the federal Department of Education portrays the industry, preferring the term early childhood education and care.

According to the blurb, “ECEC benefits children, families and the Australian economy. Quality ECEC lays the foundation for lifelong development and learning (and) leads to better health, education and employment outcomes later in life … Access to affordable ECEC means parents and carers can work, train, study and volunteer. This in turn boosts the Australian economy.”

Take it from me, all these sentences are mere assertions unrelated to any serious research findings.

Like so many public claims confidently asserted, such as ‘diversity is our strength’, the actual evidence for them is thin to non-existent.

In fact, most of the so-called research in this area is extremely poor quality, lacking proper control groups and failing to account for the many reasons some children thrive, and others don’t.

It often combines large age ranges – zero to five – where common sense tells us that the impact on babies and toddlers is likely to be very different from that on preschool children aged three and four. It’s simply advocacy to support the case for more government spending on subsidising childcare fees.

On the other hand, quality research, such as studies undertaken in Quebec that 25 years ago rolled out universal flat-fee childcare, tell a very different story. Quebec in effect became a gigantic laboratory rat, for comparison to the rest of Canada. The results were as predictable as they are depressing.

The social development of children in Quebec deteriorated. Comparing the children aged two to four who had been part of the program with their older siblings who had not revealed a greater prevalence of anxiety, hyperactivity and aggression in the former group.

The gold-standard study in this area was authored by Michael Baker, Jonathan Gruber and Kevin Milligan and appeared in the American Economic Journal in 2019. Their conclusion was “the Quebec policy had a lasting negative impact on non-cognitive skills. At older ages, program exposure is associated with worsened health and life satisfaction, and increased rates of criminal activity … In contrast, we find no consistent impact on their cognitive skills.”

Advocates of universal childcare try to wriggle around the results, predictably. For instance, they argue that the rapid rollout led to a deterioration in the quality of childcare. Well, duh. What did they expect? But it’s not the pace of the rollout, it’s the pervasiveness: Quebec did it in three years, Australia has done it over three decades. The result has not been any different: the proliferation of predators working in childcare is just the tip of the grim iceberg that is universal childcare in this country.

Centre-based childcare remains in the news for all the wrong reasons, with more instances emerging of children being mistreated by childcare workers. There have been various kneejerk reactions by the federal and state governments, including the completely predictable review in Victoria headed by former South Australian Labor premier Jay Weatherill.

Given his role at Minderoo Foundation’s early childhood development arm, Thrive by Five, arguably Weatherill is not an appropriate person to conduct the inquiry given the potential for a conflict of interest as well as strong preconceived views. But Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan no doubt sees the issue differently.

In the end, though, about the only honest thing anyone has ever said about universal childcare is what it’s really about. Spoiler alert: it’s not about what’s best for children at all.

Put simply, parents cannot work productively unless they can outsource this care for part of the day.

And that’s all it’s ever been about: turning parents into productive economic units. Who cares about the children?

Certainly not some stranger, usually a recent, third-world migrant, who’s just clocking in for a minimum wage and a stab at permanent residency in the West.