Table of Contents

As Nick Cave has written, today’s coronation of King Charles III “will more than likely be the most important historical event in the UK of our age. Not just the most important, but the strangest, the weirdest”.

Cave meant the latter entirely as high praise. The “strangeness” of rituals like the coronation, he said, is that they bring us “the uncanny, the stupefyingly spectacular, the awe-inspiring”. Cave wrote that the late Queen “actually glowed” when he met her.

For her part, the Queen, aged eleven, wrote that her own father’s coronation had filled Westminster Abbey with a “haze of wonder”.

Whining, grouching, sneering republicans are incapable of feeling any of that. Their shallow instinct is to jeer at “outmoded rituals”. That, from the same mob who come over all solemn at the “Welcome to Country”, conjured from thin air in 1976.

The coronation ritual “harks back to a bygone age”, scoffs The Australian’s Troy Bramston.

Of course it does, you lackwit dolt. It’s meant to.

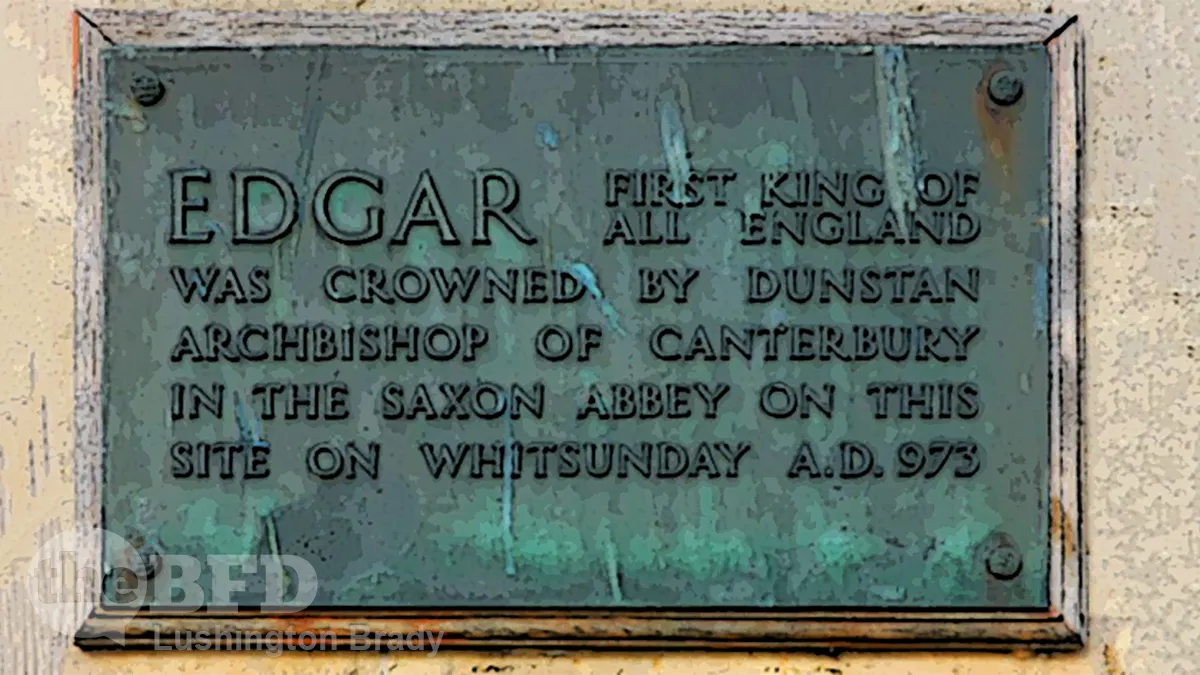

The coronation, at its core, rests on three elements that were defined in the tenth century, when Edgar was crowned King of All England, welding the warring little Anglo-Saxon kingdoms into a united realm that would, over the next millennium, come to rule a quarter of the world’s people.

First of the three elements are the “oath of justice” and the liturgy of annointment.

The oath warns the new monarch to judge righteously, protect the weak and follow “wise and sober counsellors”. Should he or she fail to do so, “the end is destruction”.

The liturgy reminds the monarch that they are no longer who they were before they took the crown.

Central to the anointment liturgy is the casting away of the old life, initially by rending the monarch’s shirt, as in the Hebrew Bible’s rite of mourning, and later in the Middle Ages by shrouding the monarch’s robes with a simple white tunic shorn of luxury, the colobium sindonis.

And central too in the anointment is the presence of four swords – the sword of state and the three swords of justice – which reflect the virtues of strength, honour, fidelity and mercy the crown requires to defend the realm and impartially administer justice.

All of which is to remind the monarch that, in words that would light the dull eyes of a millennial like Bramston: with great power comes great responsibility.

Third and last are the reminders of human mortality in a universe that has survived those who came before and will survive those who come after.

The Coronation Chair, left empty for decades at a time between coronations, reminds the monarch that he or she is indeed merely mortal. Many have come before them; in time to come, new monarchs will take the chair to replace them. The Stone of Scone, beneath the Chair, is a reminder of the mutual pact, the covenant between God and his creation. The pavement beneath their feet, commissioned by Henry III in 1272, denote the spot as the “primum mobile”: the turning-point.

It is those three elements – the promise of justice, the gift of grace and the fusing of the here and now into the boundlessness of time and space – which underpin the coronation’s solemnity. But their implications over the millennia stretch far beyond the ceremony itself.

The Oath of Justice is as consequential for democracy as the Magna Carta, signed (albeit unwillingly) by another English king three hundred years later. It is cited as “‘the starting point’ of modern liberal constitutionalism”: “an explicit binding of the government to the law which is its superior”.

The anointment is no empty religious ritual, either: it had huge consequence in mediaeval law.

The anointment was viewed as making the English monarch a “gemina persona” – a twinned person with divine and temporal natures – was instrumental in ensuring the supremacy of the courts, for it meant that a wrong committed in the monarch’s name could not possibly have been genuinely willed by the monarch, as it would have contradicted his divine nature.

Any breach of the Magna Carta could therefore be overturned by the ordinary courts of common law, as Edward Coke, the Elizabethan era’s towering jurist, held in 1616.

It was to defend that principle and entrench its own sovereignty that parliament updated and extended the oath, and made it obligatory, in the Coronation Oath Act (1688), the Bill of Rights Act (1689) and the Act of Settlement (1701), which are rightly viewed as pillars of British freedom.

Those whining about the coronation ceremony, and its supposedly “outmoded” ceremonies are missing the point. With typically blinkered modern vision, they fail to see past the glitter of the pomp to its essential meaning. As William Gladstone wrote, the trappings of the coronation are “far less imposing than the profound truth of its idea”.

It is also why Gladstone insisted the “noble and august ceremonial” needed to endure not merely as a way of enthroning the sovereign – whose power was certain to wane in the decades ahead – but also of ritually rededicating the nation to the “profound truth” that links faith and freedom, duty and fidelity, the rule of law and liberty under God.

The quibbling mini-minds of squalling republicanism would do well to reflect that the meaning of the coronation ritual has resounded through more than a thousand years of liberal democracy. Those foot-stamping must be reminded that, far from antithetical to democracy, our constitutional monarchy is essential to it.

Dunstan’s coronation oath is the rock on which Australian democracy was built – and to celebrate the fact that alone in Europe, the oath survived for century upon century, spawning free countries and free peoples around the globe.

The Australian

God Save the King. My younger self would be astonished at saying such a thing, with perfect sincerity. But then, your younger self was, as Terry Pratchett wrote, “a twerp”. Nick Cave concurs: young Nick Cave was, in all due respect to the young Nick Cave, young, and like many young people, mostly demented, so I’m a little cautious around using him as a benchmark for what I should or should not do.

So, I say to my younger self, without a blush of embarrassment: God Save the King.