Table of Contents

Joanne Nova

A prize-winning science graduate in molecular biology. She has given keynotes about the medical revolution, gene technology and aging at conferences. She hosted a children’s TV series on Channel Nine, and has done over 200 radio interviews, many on the Australian ABC. She was formerly an associate lecturer in Science Communication at the ANU. She’s author of The Skeptics Handbook which has been translated into 15 languages.

During the hottest part of the Holocene, for thousands of years, there were deep lakes filled with water in the middle of the Sahara Desert. From 9,500 years ago to 6,000 years ago the monsoons rained on the Sahara, freshwater plankton frolicked in the lakes, and greenery grew far and wide. The wetter conditions made it possible for “widespread human occupation and the development of agriculture across North Africa”. Amazingly, that last quote comes from Kuper and Kropelin fully 17 years ago. Strangely the UN experts don’t mention very often that in the warmer world not that long ago, the hyperarid Sahara desert was rich, green and filled with water. We wouldn’t want people to start wondering if climate change might mean Chad and Libya could be nicer places for Africans to live? Instead we’re told that global warming will turn into our whole world into the Saharan desert, only to find out that in a warmer world even the Sahara didn’t turn into the Saharan Desert.

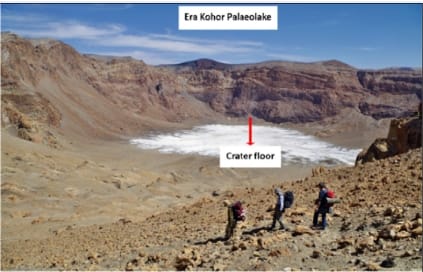

There once was a lake here…

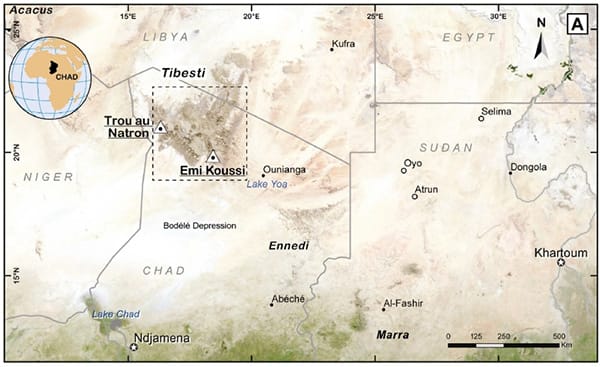

The new study by Yacoub et al shows how the water came and went in more detail, in the Tibesti Volcanic Massif (TVM) of northern Chad, but they cite 20 years of other studies that show a lost rich Saharan wilderness. The period is quietly known in academic circles as the African Humid Period (AHP).

So yet again we find that the climate on Earth has always changed, that lakes, forests, and rainfall came and went without any input from coal-fired plants or SUVs and that solar panels probably would not have saved the once great green Sahara from turning into a hyperarid desert. We claim to have expert climate models, but we don’t really know why these big shifts happen, or how fast they occurred or what caused them – they are vaguely ‘linked’ to the changes in sunshine that happen due to our orbit.

But if we are still debating whether it ended quickly or gradually, then obviously we haven’t got a good grip on the driving forces.

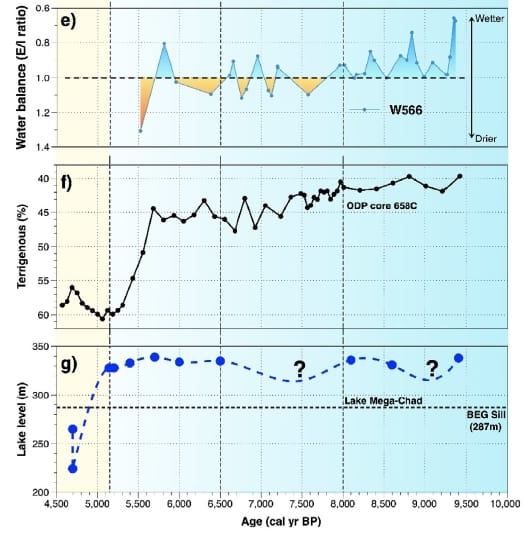

7,020 years ago freshwater plankton lived and died leaving behind their silica skeletons.

Things started to dry out about 5,500 years ago.

The introduction to Yacoub et al is eye-opening. It is a literature review of scores of papers showing just how wet and green the Sahara was, and then wasn’t – in the blink of a geologic eye. There is still debate about how fast the green era disappeared.

An extensive array of palaeoclimatic records (Shanahan et al., 2015; Holmes and Hoelzmann, 2017) and archaeological investigations (Cremaschi et al., 2014; Manning and Timpson, 2014) have shown that during this humid period, large parts of the present-day hyperarid Sahara and the semi-arid Sahel regions were much wetter and ‘greener’ than today, and thus characterized by grasslands with tropical trees (Hély and Lézine, 2014), hosting numerous lakes (Hoelzmann et al., 2004; Drake et al., 2011) and incised by vast fluvial networks (Skonieczny et al., 2015). This early-to-mid Holocene period of greening of the Sahara, named the Green Sahara period (Claussen et al., 2017), was linked to the low precession in Earth’s orbit associated with high boreal summer insolation that induced the northward extension of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and the intensification of the associated African monsoonal rainfall belt (Kutzbach and Liu, 1997; deMenocal, 2015; Dallmeyer et al., 2020). These wetter conditions enabled widespread human occupation and the development of agriculture across North Africa (Kuper and Kröpelin, 2006; Manning and Timpson, 2014). After the mid-Holocene, the southward retreat of the monsoonal rainfall belt led to drier conditions that provoked the desiccation of most lakes (Gasse, 2000) and critical demographic shifts (Manning and Timpson, 2014), sealing the end of the AHHP. Throughout the African continent, the timing and magnitude of the termination of the AHHP were probably variable in space and time (Shanahan et al., 2015) and there is a long-standing and on-going debate about whether the end of the AHHP and the subsequent drying of the Sahara was abrupt or gradual (deMenocal et al., 2000; Holmes, 2008; Kröpelin et al., 2008; Bard, 2013; Collins et al., 2017; Ménot et al., 2020; Chase et al., 2022).

REFERENCES

Yacoub et al., (2023), The African Holocene Humid Period in the Tibesti mountains (central Sahara, Chad): Climate reconstruction inferred from fossil diatoms and their oxygen isotope composition

Kuper and Kropelin, (2006): Climate-controlled holocene occupation in the Sahara: motor of africa’s evolution. Science 313, 803e807. https://doi.org/10.1126/ science.1130989

This article originally appeared at JoNova.