Table of Contents

Lindsay Mitchell

Lindsay Mitchell has been researching and commenting on welfare since 2001. Many of her articles have been published in mainstream media and she has appeared on radio, tv and before select committees discussing issues relating to welfare. Lindsay is also an artist who works under commission and exhibits at Wellington, New Zealand, galleries.

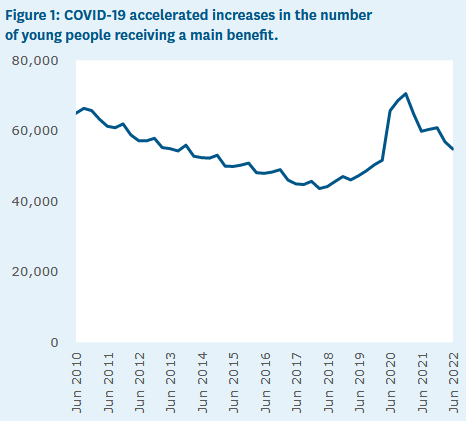

Yesterday MSD issued some insights into how young people (16-24 years-old) are faring in the benefit system. Searching for some good news, their first key finding described how young people “have recovered much faster from the economic effects of the pandemic compared to the Global Financial Crisis.”

The government response to covid drove a very steep increase in young people going on a benefit so naturally enough you would expect a fairly steep corresponding decrease. By contrast the GFC presented a gradual increase and decrease in numbers.

Note that by June 2022 54,900 young people on benefits is still well above their lowest level in late 2017 which coincides with the change in government and Ministers. Numbers on Sole Parent Support and Supported Living Payment are on an upward trend.

Next, the report waxes lyrical about supporting young people to engage in education and gaining skills. Shame about the polytechnic reforms fiasco described by Otago Polytech chief executive as a “national disgrace.”

But that’s where any ‘positivity’ ends.

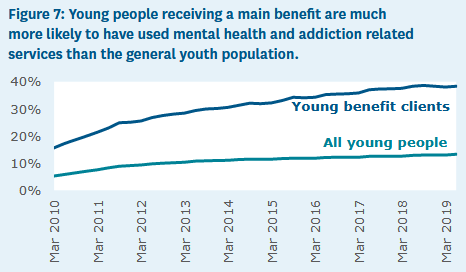

Apparently “longer-term trends” suggest young people will need more help with their mental health. This is where the truly eye-opening news begins.

“In the March 2010 quarter, 5.2 percent of young people had accessed mental health and addiction services, and this more than doubled to 13.3 percent by the June 2019 quarter.”

By 2019 almost 40 per cent of youth benefit clients had used these services. This immediately raises chicken and egg questions. While it is likely that the poor mental health precedes the benefit dependence, languishing on welfare is also not conducive to good mental wellbeing. Undoubtedly a two-way mechanism operates.

Notice too that this upward trend preceded any sign of the covid pandemic.

The next piece of information is even more appalling.

“When looking specifically at young people currently receiving a benefit, the 2019 Social Outcomes Model estimated that they would spend an average of 16.5 years receiving a main benefit over their future working lives; this increased to 19.1 years in 2021.”

An almost three-year increase in over just two years.

This growing propensity to fail to achieve independence is because of “complexity” apparently. The greater the number of risks – eg. police, justice or Oranga Tamariki involvement, NCEA failure, school suspension or inter-generational welfare dependence – the longer the duration of stay on welfare will be. It is easy to understand that with youth crime and educational failure in the ascendancy, these numbers can only spiral upwards.

The report culminates with a down-playing dose of self-deception which sadly seems all too familiar amongst today’s public service employees:

“While there have been rapid decreases in main benefit numbers for young people who receive a main benefit, some vulnerabilities remain.”

The only “rapid decreases” to occur were after the ‘end’ of the pandemic and among youngsters who would probably never have been in the benefit system if it hadn’t been for the government’s covid response.

Otherwise, the underlying trend is of growing reliance and greater dysfunction among young people living through crucial scene-setting years which may determine the rest of their lives.

What a sorry mess.