Table of Contents

Lindsay Mitchell

Lindsay Mitchell has been researching and commenting on welfare since 2001. Many of her articles have been published in mainstream media and she has appeared on radio, tv and before select committees discussing issues relating to welfare. Lindsay is also an artist who works under commission and exhibits at Wellington, New Zealand, galleries.

The Salvation Army’s latest State of the Nation 2023 report draws on data from Oranga Tamariki (formerly CYF) and tells us, “The number of children under 2 years of age entering care is down from 440 in 2018 to 133 in 2022…”

Finally, some good news from a public service agency.

More than two thirds of children in state care are Maori but the number dropped from 15 in 1,000 in 2017 to 10 in 1,000 in 2022. According to the report this is “a result of sustained advocacy from Maori for changes in the child protection system.”

A prime example of this is Dames Naida Glavish and Tariana Turia campaigning to stop the practice of uplifting a newborn from a mother whose older children had already been removed from her care.

Back to the report. For children of all ages, notifications of abuse and neglect have fallen significantly, as have substantiations. The reports states, “…total entries into care for all age groups are less than half the level of 2018.”

These really are quite staggering reductions. One might conclude children are safer than previously.

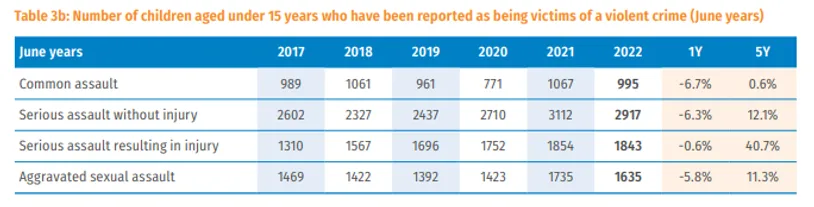

However, police statistics (contained in the same report) show child victims of violence trending in the opposite direction including a 41% increase in serious assaults resulting in injury between 2017 and 2022:

Oranga Tamariki (OT) and the Police appear to be operating in different environments.

What could explain these divergent trends?

It is possible that high level violence has increased while intermediate or low-level violence has decreased. That seems implausible though. Serious assault would surely be associated to some degree with entries into care.

Another spanner in the works arises from the Police being duty-bound to make a notification to OT when a child(ren) is at the scene of a family violence incident (even if the child is only a witness). According to Police’s latest annual report, “In 2021/22 there were 175,573 family harm investigations recorded – a 47% increase from 2017.” This makes OT’s numbers even odder.

Consider too the large increase in gang numbers. Parliamentary documents record, “…the NGL [National Gang List] increased from 4,361 in February 2016 to 7,722 in April 2022 with the majority Maori.” Unsurprisingly children growing up in gang environments have risks of abuse and neglect many times greater than other children. More children are in benefit-dependent households which also carries higher risks.

Another possibility for the diverging trends could be that OT’s thresholds for undertaking action have shifted. It is almost certain that the organisation will be struggling with staff shortages. As recently as December 2022 the Chief Executive of OT said, “…we are working with the Social Workers Registration Board to tackle nationwide social worker shortages.”

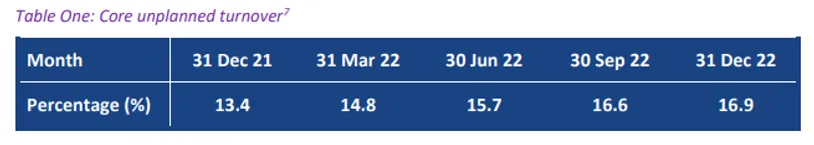

Staff turnover is relatively high and increasing:

According to Newsroom, a “long time Oranga Tamariki employee” left at the end of last year because “despite being well-funded, the money is not being used where it’s needed most”:

“Most of the difficulty for me came from the absolute lack of resources available to keep tamariki and rangatahi safe and free from ongoing harm, where we had no option but to try and cobble together a safe place for them made up of rotating caregivers and motel units.”

Are decisions being made to not admit children into care simply because there are no practical options for doing so?

The other question the ex-employee’s comment raises is, where’s the money going? Like every other arm of the public service OT has invested heavily in their commitment to the treaty; what that looks like and how it gets measured. Their Maori Cultural Framework lays this out. Schooling all employees in these principles and processes must take time and money. Whenever systems become over-bureaucratised the practitioners cannot get on with their core duties.

A further possibility, given recent high-profile data errors at Te Whatu Ora (NZ Health), is mis-recorded or mis-reported statistics.

The report itself suggests that notifications to OT, which often hail from schools and pre-schools, had reduced due to Auckland covid lockdowns. It did not mention high absenteeism.

To their credit, about the OT numbers the authors write, “…we do not believe the lower figures can be seen as suggesting that children were safer.”

In fact, they do not hide their scepticism:

“The report by the Independent Children’s Monitor in early 2022 and the reports on the way the system failed the child and family in the Malachi Subecz case are two examples of multiple reports and research highlighting the ways that the state care system is continuing to fail too many children, and particularly tamariki Maori.”

Oranga Tamariki’s data sits in stark contrast to that of the Police.

What is going on – or not going on – at Oranga Tamariki is of grave concern. All families and their intimate circles have the right to make provision for their own children if safely able to – Maori and non-Maori. OT’s stated goal that ‘no tamaiti Maori will need state care’ is indisputable. My fear though is that reducing numbers of entries into care has the same etiology as reducing numbers of surgeries performed in hospitals. Fewer operations do not mean the population is getting healthier.

On the balance of evidence, the answer to ‘Are children safer or not?’ is most likely negative. In which case, regrettably, there is no good news after all.