Table of Contents

Back in 2010 the Rockefeller Foundation produced a paper entitled Scenarios for the Future of Technology and International Development which postulated four scenarios for what the future might look like.

In the introduction, answering the question of “Why scenarios?” the report includes this:

Scenario planning is a methodology designed to help guide groups and individuals through exactly this creative process. The process begins by identifying forces of change in the world, then combining those forces in different ways to create a set of diverse stories—or scenarios—about how the future could evolve

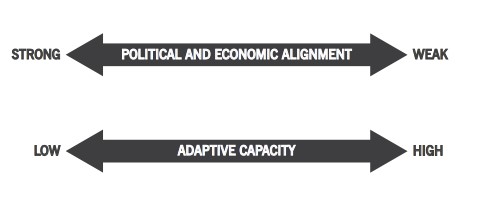

The scenarios looked at two uncertainties chosen from a long list.

The two chosen uncertainties, introduced below, together define a set of four scenarios for the future of technology and international development that are divergent, challenging, internally consistent, and plausible. Each of the two uncertainties is expressed as an axis that represents a continuum of possibilities ranging between two endpoints.

[…]

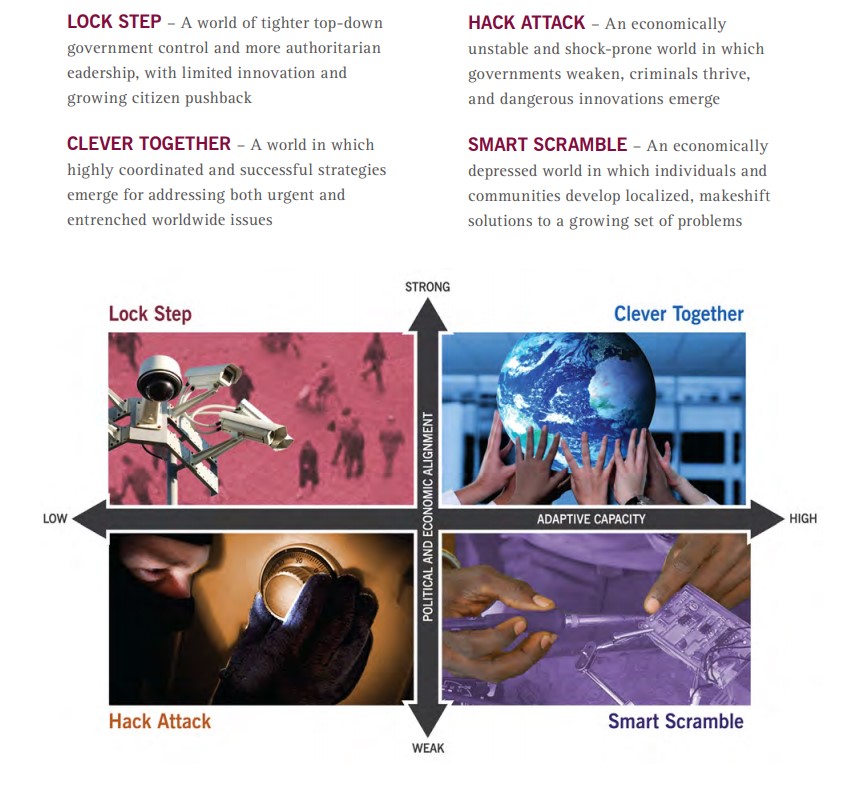

Once crossed, these axes create matrix of four very different futures:

All very interesting, academic and erudite I’m sure. Let’s have a peek at the Lock Step scenario which results in “A world of tighter top-down government control and more authoritarian leadership, with limited innovation and growing citizen pushback.”

This is beginning to sound familiar ….

So without further comment here are the first few paragraphs, untouched apart from a little added emphasis.

In 2012, the pandemic that the world had been anticipating for years finally hit. Unlike 2009’s H1N1, this new influenza strain—originating from wild geese—was extremely virulent and deadly. Even the most pandemic-prepared nations were quickly overwhelmed when the virus streaked around the world, infecting nearly 20 percent of the global population and killing 8 million in just seven months, the majority of them healthy young adults. The pandemic also had a deadly effect on economies: international mobility of both people and goods screeched to a halt, debilitating industries like tourism and breaking global supply chains. Even locally, normally bustling shops and office buildings sat empty for months, devoid of both employees and customers.

The pandemic blanketed the planet—though disproportionate numbers died in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central America, where the virus spread like wildfire in the absence of official containment protocols. But even in developed countries, containment was a challenge. The United States’s initial policy of “strongly discouraging” citizens from flying proved deadly in its leniency, accelerating the spread of the virus not just within the U.S. but across borders. However, a few countries did fare better—China in particular. The Chinese government’s quick imposition and enforcement of mandatory quarantine for all citizens, as well as its instant and near-hermetic sealing off of all borders, saved millions of lives, stopping the spread of the virus far earlier than in other countries and enabling a swifter postpandemic recovery.

China’s government was not the only one that took extreme measures to protect its citizens from risk and exposure. During the pandemic, national leaders around the world flexed their authority and imposed airtight rules and restrictions, from the mandatory wearing of face masks to body-temperature checks at the entries to communal spaces like train stations and supermarkets. Even after the pandemic faded, this more authoritarian control and oversight of citizens and their activities stuck and even intensified. In order to protect themselves from the spread of increasingly global problems—from pandemics and transnational terrorism to environmental crises and rising poverty—leaders around the world took a firmer grip on power.

At first, the notion of a more controlled world gained wide acceptance and approval. Citizens willingly gave up some of their sovereignty—and their privacy—to more paternalistic states in exchange for greater safety and stability. Citizens were more tolerant, and even eager, for top-down direction and oversight, and national leaders had more latitude to impose order in the ways they saw fit. In developed countries, this heightened oversight took many forms: biometric IDs for all citizens, for example, and tighter regulation of key industries whose stability was deemed vital to national interests. In many developed countries, enforced cooperation with a suite of new regulations and agreements slowly but steadily restored both order and, importantly, economic growth. […]

There was a little ray of hope at the conclusion.

By 2025, people seemed to be growing weary of so much top-down control and letting leaders and authorities make choices for them. Wherever national interests clashed with individual interests, there was conflict. Sporadic pushback became increasingly organized and coordinated, as disaffected youth and people who had seen their status and opportunities slip away—largely in developing countries—incited civil unrest. […] Even those who liked the greater stability and predictability of this world began to grow uncomfortable and constrained by so many tight rules and by the strictness of national boundaries. The feeling lingered that sooner or later, something would inevitably upset the neat order that the world’s governments had worked so hard to establish.

If you wish to read more, click on the link below.

Scenarios-for-the-Future-of-TechnologyDownload

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.