Table of Contents

I don’t know why foreigners are so terrified of Australian wildlife. I mean, sure we’ve got three of the world’s nine most-deadliest snakes. Then there’s the deadly blue-ringed octopus, the also-deadly stonefish and the likewise potentially lethal cone snail.

And then there’s the dropbears and hoop snakes…

Oh, and now, possibly the deadliest spider in the world.

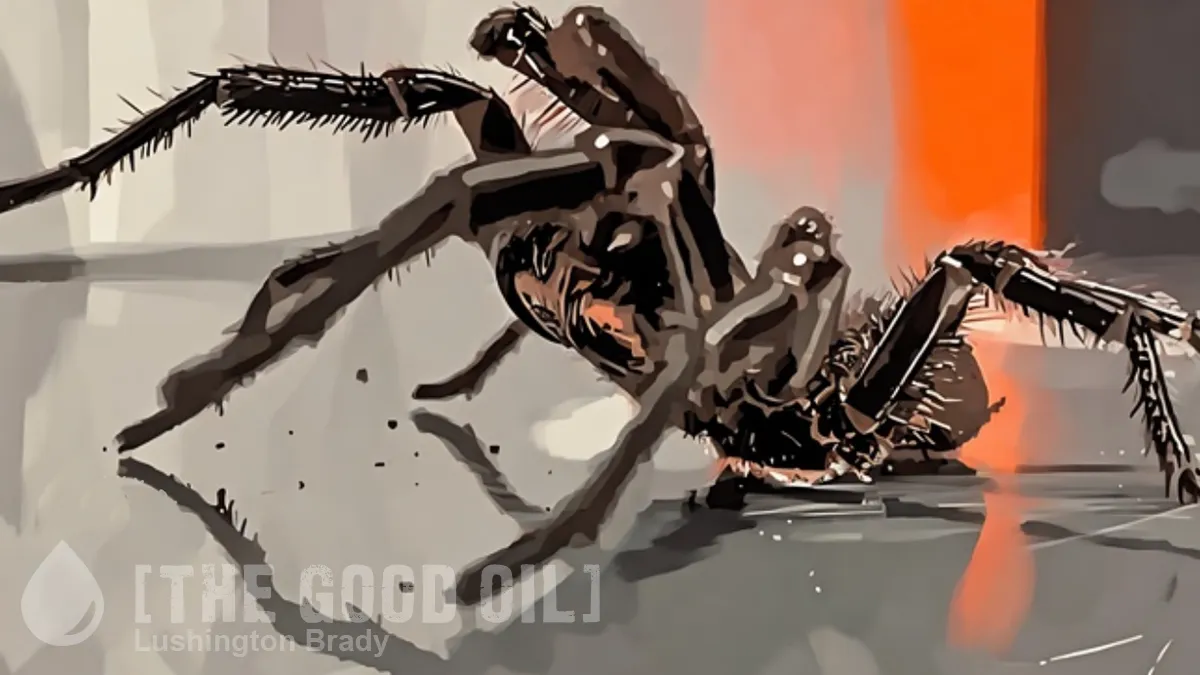

Scientists have declared the Sydney funnel web – hallowed and feared as the world’s most venomous spider – is in fact three separate species. And one of the spiders, new to science, is a certified monster.

Because, if there was one thing wrong with funnel webs, it’s that they weren’t big enough.

The new species, nicknamed “the big boy”, was given the scientific name Atrax christenseni after the Central Coast spider-wrangler who led scientists to its discovery.

‘Spider wrangler’. Now there’s one you don’t often hear of on Career Day.

That man, Kane Christensen, joined the Australian Reptile Park in 2003 as a volunteer venom milker. Each summer the park near Gosford asks the public to drop off captured funnel webs for the production of antivenom.

Almost immediately, Christensen began to notice a procession of abnormally huge funnel webs, big as men’s palms. They barely fit in the park’s holding jars. People mistook them for huntsmans. When one prowled across a benchtop, you could hear its footsteps.

Good Lord. Read that again: you could hear its footsteps.

It gets more terrifying.

In 2018, the park hailed the arrival of their biggest ever funnel web, dubbed Colossus, and grabbed international headlines. A normal male has a 2.5 centimetre body length. This spider was double that size.

Then came Megaspider, brawny enough to go toe-to-toe with a tarantula, in 2021. Next it was Hercules, a beast with an eight-centimetre leg span packing fangs long and strong enough to pierce a fingernail.

And even Hercules was usurped this season by a 9.2-centimetre arachnid dubbed Hemsworth after Australia’s hunky Hollywood brothers. It was the largest funnel web ever found, the park said.

With so many gigantic spiders cropping up, the question became whether these were just unusually big-boned lads, or a new species of funnel-web altogether. To figure it out, scientists spent a lot of time peering at the spiders’ va-jay-jays and pee-pees. Don’t believe me? Read on.

The scientists dissected the sperm receptacles of females and scrutinised differences in their structure under microscopes. They also found the male’s embolus, a sperm-transferring needle that grows from the leg-like appendages beside a spider’s fangs called the pedipalps, was much longer and twisted in the “big boy” spiders.

Paired with two years of DNA analysis in Germany, these morphological findings confirmed Gray’s long-held suspicion. The famous Sydney funnel web was split into three species.

Now, if you’re me, you’re wondering why they just didn’t do a DNA analysis. Scientists have to have their fun somehow, I guess.

And we get to have, not one, not two, but three! species of deadly funnel webs.

The “real” Sydney funnel web, Atrax robustus, calls the north shore and Central Coast home. “That’s the heartland,” Dr Helen Smith, an arachnologist at the museum and co-author of the BMC Ecology and Evolution study, said.

The second type, an almost identical but nonetheless different species dubbed the southern Sydney funnel web, was given a revived classification from the past: Atrax montanus […]

Then there’s the big boys.

“They’re actually a totally new species. They’re restricted to about 25 kilometres around Newcastle,” Smith said. “So we’re calling that the Newcastle funnel web.”

Odd as it may seem, the priority is protecting the spiders from humans, rather than vice versa.

The exact locations of the Newcastle funnel webs have been obscured from maps due to conservation fears.

“As soon as collectors get a whiff of a new species, there’s a huge trade in invertebrate specimens in Australia,” Smith said. “They could make quite a dent in the population.”

The good news is that funnel-web bites are rarely fatal any more, although recently an 11-month-old baby was put in a critical condition from a bite, before recovering. No one has died, though, since an antivenom was developed in 1981. The same antivenom will work for even these big bastards.