Table of Contents

“The book is better than the movie” is an old truism: but is it always true?

Mostly, yes. The added bonus of books is the freedom of the reader to interpret, and the freedom of the author to add layers of complexity and nuance that cinema simply can’t encompass. Mostly because cinema is a medium that is necessarily compressed, in time and in space.

Consider the Peter Jackson The Lord of the Rings films, adaptations of fiercely-loved books that are almost universally approved by fans. But the films excised a great deal of material simply because of the demands of cinema. For instance, the hobbits’ journey from the Shire to Rivendell, instead of an almost leisurely journey that slowly builds in menace and pace, is an action-packed set-piece from start to finish. The former wouldn’t work at all in cinema, the latter does, perfectly. Even if that means excluding entire chapters, such as the Old Forest and the Barrow-Downs.

But the films are still a poor second-cousin to the book. Indeed, there are many aspects of the films that I thoroughly detest (the character-assassinations of Gimli, Faramir and Denethor, for a start).

The book is better than the movie.

Very rarely, though, the reverse is true. Here are a couple that spring to my mind.

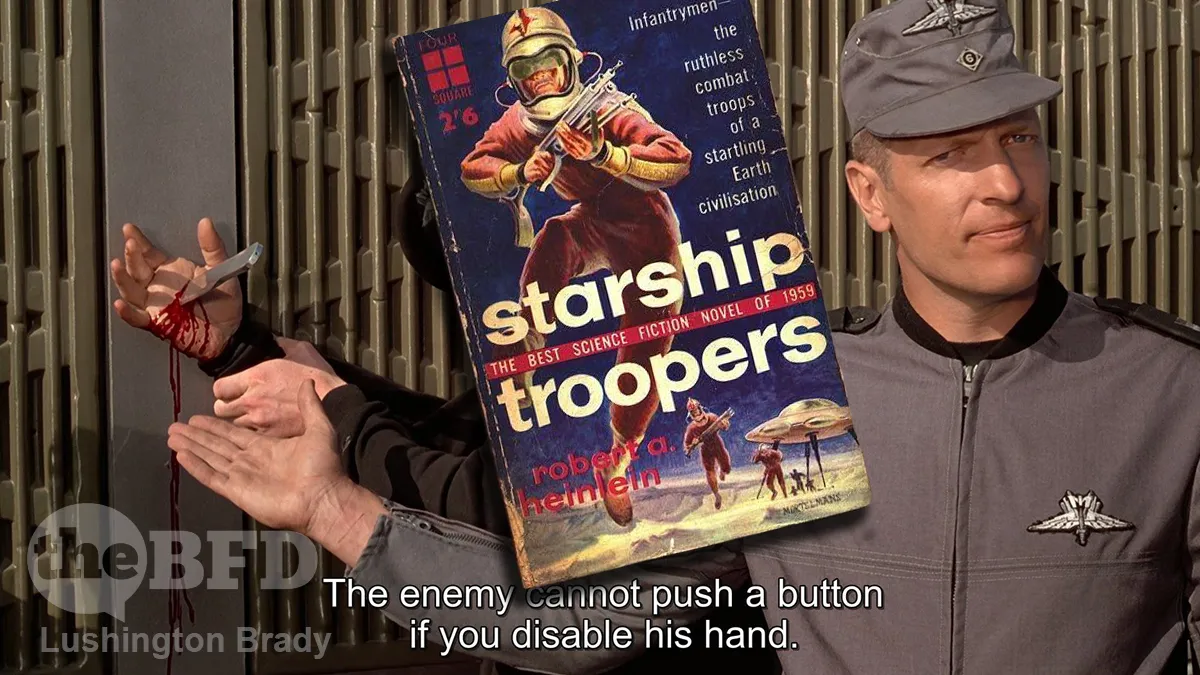

Starship Troopers

(Robert A. Heinlein 1959/Paul Verhoeven 1997)

Okay, this is getting pretty close to heresy for me, as a thoroughgoing Heinlein fan. But the key difference between the book and film is how seriously they take themselves. Heinlein’s novel isn’t a bad book: it just takes itself too seriously.

Contrary to the common screeching that Heinlein’s book is “fascist” and “racist”, it’s actually extraordinarily progressive in many ways. For a start, its hero, Juan “Johnny” Rico, is a native of Argentina. Many of its other lead characters are also Hispanic. All pilots in the Federal Service are women. Remember: this was a book written in 1959.

Where it falls down, though, is its po-faced didactism. Heinlein subjects the reader to endless, didactic lectures on “History and Moral Philosophy” that are almost as tedious as anything by Ayn Rand.

By contrast, director Paul Verhoeven turns Heinlein’s didactism into high comedy, playing Lt. Rasczak’s (Michael Ironside) lectures into self-parodies. And who can keep a straight face when Sgt. Zim (Clancy Brown) skewers a recruit’s hand to demonstrate the usefulness of a knife in a nuke fight? “Medic!”

The Haunting of Hill House/The Haunting

(Shirley Jackson 1959/Robert Wise 1963)

I only recently read Jackson’s novel, while the movie has been a favourite from a young age. The novel was one of the most disappointing books I’ve ever read. Robert Wise’s film scared the pants off me — and still does. Jackson’s novel, though, is just faintly irritating.

Most of the novel is written in a flippant style with endless light-hearted banter between the characters, so it comes off as more of a second-rate attempt to imitate Oscar Wilde than Henry James. Almost nothing happens for at least half the novel: it’s all witty conversation and drinks by the fire. Granted, inexplicable events start to happen, but even the blood writing on the walls is about as scary as the bleeding painting in The Ghost and Mr. Chicken. Perhaps it’s intended to be a “psychological thriller”, but, frustrated, I ended up asking, like Seth Goldblum in Jurassic Park, “Ah, now eventually you do plan to have ghosts in your ghost story, right?”

Hell House/The Legend of Hell House

(Richard Matheson 1971/John Hough 1973)

Both the title and plot of both film and book are almost identical to Shirley Jackson’s novel: a scientist of the paranormal gathers a group to test the truth of a legendarily haunted house. Where both depart, though, is that what was barely hinted at in the one, is shouted with an incessant din in the other: perversion and repressed sexuality bursting into very much not suppressed sexuality.

Matheson’s book would undoubtedly have been shocking in 1971: sadism, lesbianism, crucifixes with enormous wooden erections, and so on. But the overall effect is frankly tedious, like a small child shouting “bum!” over and over to try and get a reaction from the grown-ups.

Necessarily for 1973, the movie tones down the sex stuff, without getting rid of it altogether. The result is that the film is genuinely unsettling rather than mind-numbingly crass.

The Princess Bride

(William Golding 1973/Rob Reiner 1987)

William Golding adapted his own novel for the screen — and in doing so pared down the self-indulgence to bearable levels.

The result is that the film is a beloved classic, and (much as it galls me to admit of the flatulent Reiner) one of the few perfect movies to grace the screen. While the film retains the novel’s knowing, parodic comedy, it ditches the endless nudging-and-winking of the novel. One can imagine a New Yorker type reading the novel and chortling, “Oh, how droll…” as they swirl their snifter of brandy.

Everybody loves the movie.

Besides, the novel doesn’t have Peter Cook’s brilliant scene-stealing monologue as the Solemn Clergyman.

So, there are just a few movies that exceed the books they’re based on. List any of your own in the comments.