Table of Contents

A common theme that’s emerged in the artists I’ve profiled in this series is that they’ve either been hugely influential or created best-selling works without ever becoming household names. Murray Grindlay and George Young, for instance: you definitely know and love a great many of their songs, although you didn’t know their names. Others, like Dario Argento, are famous among fans of their particular genre, but barely known outside it.

This brings me to this week’s subject: Alan Dean Foster.

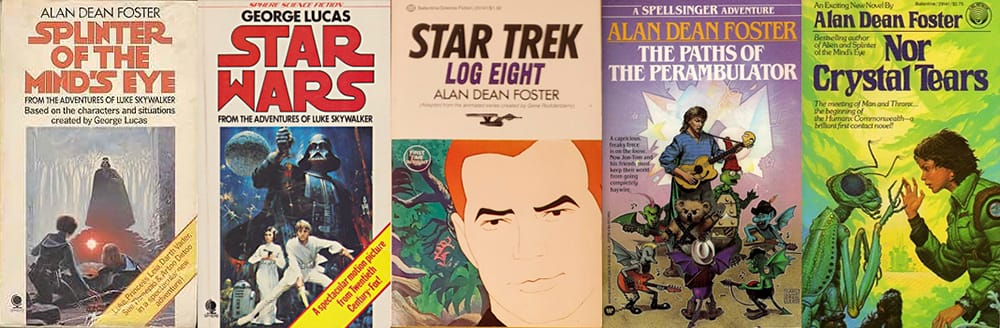

Foster is a science fiction and fantasy author who began writing bestsellers in the 1970s, but which were associated with other people’s work and franchises, which are household names, while Foster isn’t. That’s because his career first took off as a ghostwriter or official noveliser of some of the biggest science fiction franchises in cinema: Star Wars, Star Trek and Alien.

Such work is often badly under-rated, however well the authors translate cinematic narratives into rich prose and simultaneously expand the necessarily limited worlds of cinema into dense sub-creations. Orson Scott Card’s novelisation of The Abyss, for instance, expands the film enormously by expanding even minor characters’ backgrounds in ways that film-maker James Cameron never even indicated, but which he fully approved of.

That’s because good novelisers and ghost-writers like Card and Foster have, in fact, a rare talent: to be able to capture another person’s voice, extend existing fictional universes and meet tight studio deadlines.

Alan Dean Foster published his first story in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1968 and his first novel, The Tar-Aiym Krang, in 1972. But, from early on, he was also known in professional circles as a reliable and fast ghostwriter. Such projects provided Foster with the envy of any professional writer: steady work and economic stability. During the 1970s, studios looking to expand the reach of their properties frequently turned to him. While many specific ghost-writing assignments remain confidential, it is widely known that Foster worked on Star Trek projects, novelisations for television series and other behind-the-scenes writing.

What made Foster valuable was not merely speed, but an ability to treat adaptation as genuine storytelling, not transcription. His background, with degrees in both political science and film studies, no doubt made him ideally suited for such work. His prose added psychological nuance, descriptive richness, world-building detail, and thematic depth – all while respecting the tone of the source material. These strengths would soon find their fullest expression in a project that exploded his reputation beyond genre circles.

Throughout the 1970s, Foster authored multiple Star Trek works, most notably the 10-volume Star Trek Log series, from 1974–1978, adapting episodes of Star Trek: The Animated Series and expanding them far beyond their brief screen time. His adaptations often doubled or tripled the narrative scope of the originals, adding internal politics, alien cultures and character motivations.

In 1976, Alan Dean Foster was hired to ghost-write the novelisation of an obscure, as-yet-unreleased space fantasy film by a young director named George Lucas. The book, Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker, appeared months before the 1977 film premiere. I well remember kids at my school reading it, as we eagerly awaited this new movie we’d started seeing trailers for (I first saw a trailer for Star Wars on a first-run screening of Logan’s Run: few things sum up the epochal shift in popular culture, for better or worse, that Star Wars ushered in).

But Foster’s name appeared nowhere on the cover. Instead, “George Lucas” was credited as author, a standard practice at the time. Foster was given a screenplay and early production art, along with the freedom to add internal monologue, expanded backstory and richer descriptions. His work helped set up Star Wars as a literary as well as cinematic phenomenon and paved the way for the expanded universe that still dominates pop culture half a century later. Foster’s contributions included elaborating on the political situation surrounding the Empire and added texture to locations and technology that the film could only briefly show. More importantly for George Lucas, the early release of the novelisation was key to building up expectations for the forthcoming film.

The fact that the book was credited to Lucas, with Foster’s own name never appearing anywhere, didn’t faze the author.

Not at all. It was George’s story idea. I was merely expanding upon it. Not having my name on the cover didn’t bother me in the least. It would be akin to a contractor demanding to have his name on a Frank Lloyd Wright house.

Foster’s novelisation for Star Trek: The Motion Picture in 1979 was similarly credited to Gene Roddenberry. Many fans consider the book superior to the film, as it clarifies the philosophical stakes and adds emotional clarity. No doubt Foster cried all they way to the bank.

Besides, the massive success of the film boosted Foster’s own career, even if he often still remained in the shadows. Even before Star Wars launched, for instance, Lucas was looking ahead to sequels and commissioned another novel, this time with Foster’s name alone on it. Still, Lucas was hedging his bets: if Star Wars performed only modestly, he needed to convince studios they weren’t throwing good money after bad. So Splinter of the Mind’s Eye was a much more low-key affair, for a prospective low-budget sequel, than the sprawling space opera of Star Wars: set on just one planet and featuring only Luke and Leia.

Somewhat awkwardly, in retrospect. With The Empire Strikes Back well in the future, Lucas had yet to hit on the idea of Luke and Leia as secret siblings. With which hindsight, several scenes in Splinter, especially when the pair share a sleeping-bag and some (mild) romance. Unsurprisingly, Lucas later declared Splinter non-canon, even if it did introduce some key concepts, such as a crazy old Force-mentor hiding on a swamp planet, and the all-important (to the Jedi) Kaiburr crystals.

As he did with Star Wars, Foster added notable psychological depth and atmospheric to Alien’s story, a year later. He enhanced the characters’ inner lives, especially Ripley and Dallas, lending emotional resonance to what is visually a stark, claustrophobic film. Foster also expands the biology of the xenomorph, a remarkable achievement given that he was given very little to go on – especially no detailed descriptions, let alone pictures, of the creature. Hence, his novelisation relies heavily on suggestiveness and a shadowy monstrosity.

Foster also expanded on the technology of the Nostromo and the tension between the crew and the faceless corporation Weyland-Yutani. Something he carried over to his Aliens novelisation, clarifying James Cameron’s world-building, such as interstellar travel, colonial administration, and corporate policy, that the film merely hints at. He also expanded on Colonial Marine culture, Ripley’s PTSD, Newt’s tragic backstory, and the social dynamics of the terraforming colony.

Foster would later return to the franchise with original novels, including Alien: Covenant – Origins in 2017, cementing his position as one of the major literary architects of the Alien universe.

More importantly, Foster’s work on Star Wars engendered the concept, now commonplace in pop culture, of an ‘extended universe’. The massive success of Star Wars prompted a commercial empire that went well beyond toys and collectibles. Star Wars novels and comics number well into the hundreds. Other science fiction franchises, from Alien (Foster wrote the novelisations of both Ridley Scott’s Alien and James Cameron’s Aliens), to the Halo videogames and the Warhammer 40K table top games.

But Foster is far more than a translator and expander of other peoples’ ideas. His original works in SF and fantasy, while less well-known outside the fandoms of their genres, constitute a remarkable opus of their own. The Humanx Commonwealth SF universe and the Spellsinger fantasy series are his most enduring original creations, representing strikingly different expressions of his imaginative range. Though both series feature cross-species cooperation, ecological sensitivity, and wide-ranging adventure, they diverge sharply in tone, purpose, and literary strategy. Together they demonstrate the breadth of Foster’s talent: one offering a mature, expansive vision of interstellar civilization, the other a playful, satirical re-imagining of portal fantasy.

The Humanx Commonwealth is Foster’s grand project – a long-running future history centred on the alliance between humans and the insectoid Thranx. Its defining qualities are scale, ecological realism and sociopolitical nuance. Foster builds a galaxy that feels genuinely lived-in, shaped by diplomacy, trade and scientific development rather than simple conquest. Even the more adventure-oriented Pip & Flinx novels sit within a broader, evolving sociocultural context. Foster approaches alien worlds with an almost zoological curiosity: ecosystems are not backdrops but driving forces, often determining plot, culture, and technology. Though the Commonwealth books contain high adventure, they are fundamentally serious-minded, blending optimistic space opera with anthropology and environmental speculation.

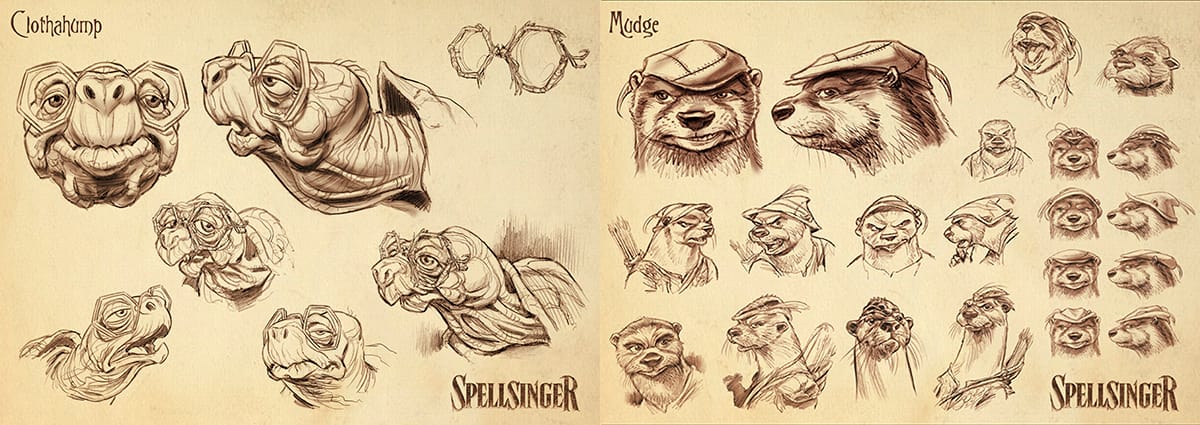

By contrast, Spellsinger is a deliberately lighter, more comedic undertaking. Its protagonist, college student and amateur guitarist Jon Meriweather, is transported to a world of talking animals where music constitutes magic. Here, Foster discards the realism and political structure of Humanx for irony, slapstick, and genre parody. Magic in Spellsinger is notoriously unpredictable, shaped by song lyrics that Foster gleefully twists into pun-laden consequences.

This central conceit – music as magic – is both strikingly original, and, at times, slightly endearingly dated. Singing Sloop John B to conjure a yacht for a sea journey is at once dangerously silly and cleverly subversive of the genre. Compared to Humanx, the world of Spellsinger’s social systems are simpler, character psychology more exaggerated, and the world itself a vehicle for humorous commentary on both fantasy tropes and 20th-century culture. Foster’s background in political science shows through, with dragons spouting Marxist gibberish, and Nazi eagles fancying themselves the master-race.

Yet beneath the humour lies recurring Foster concerns: environmental degradation, the corrupting influence of power, and the ethical responsibilities of leadership. Foster also at times introduces a level of brutal mediaeval realism not often seen in fantasy before the advent of the ‘grimdark’ genre: cute little squirrel children are bullies who mete out brutal beatings on other children, and bar fights degenerate into hacked limbs and death. Even so, the series is primarily an exercise in play, whereas Humanx is an exercise in vision.

Thematically, the two cycles reflect different facets of Foster’s worldview. Humanx presents cooperation between species as a realistic, challenging, but noble endeavour; its best moments arise from the cultural friction and mutual growth of human and Thranx societies. Spellsinger, however, frames cross-species interaction as comedy and allegory: stereotypes are exaggerated for satirical effect, yet the underlying message about empathy and communication remains intact. Where Humanx leans toward social idealism, Spellsinger leans toward cynical satire softened by friendship.

Stylistically, the prose of Humanx is cleaner, restrained, and often lyrical in descriptions of alien landscapes. Spellsinger adopts a looser, more conversational tone suited to its comedic ambitions. Foster’s versatility as a stylist is most evident when comparing the two: the same writer who meticulously constructs alien ecologies can also riff on rock lyrics to produce chaotic spell effects.

Sadly, a mooted animated cinema adaptation of Spellsinger, some years ago, doesn’t seem to have progressed beyond some tantalising character sketches.

As the two very different series, and the massive corpus of adaptations show, few American writers have had a literary career as varied, prolific, or quietly influential as Alan Dean Foster. His work as an uncredited ghost-writer and official novelizer of major science-fiction films helped shape how audiences experienced some of the most important pop-culture properties of the modern era. His original fiction demonstrates his mastery of world-building, ecological imagination, and character-driven adventure.

Together, these two halves of Foster’s career reveal a writer who is both craftsman and creator, bridging the gap between Hollywood spectacle and literary invention.