Table of Contents

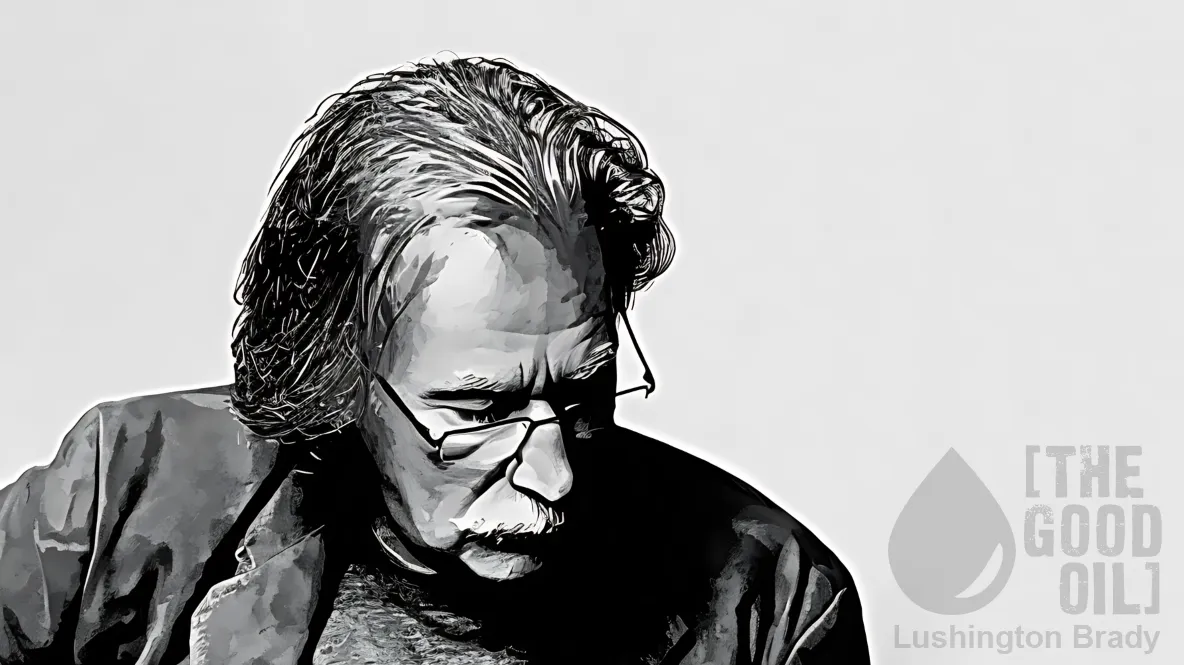

How is possible to have a number one hit and write music and songs that nearly everyone in the country will know by heart, yet your name draws a blank? Just ask Murray Grindlay.

One of New Zealand’s most adaptable and enduring figures in popular music, Grindlay’s work spans novelty hits, beloved movie soundtracks and the unsung art of the advertising jingle. For over 60 years, his career has left a mark on New Zealand popular culture that is as eclectic as it is unmistakable.

All without becoming a household name.

For those of you scratching your heads over who this ‘Murray Grindlay’ fellow is, let me just say: Shoop-shoop diddy-wop cumma-cumma wang-dang. Have a Crunchie. Bluebird, the great taste out of the blue.

Not mention: hot pools, rugby balls, McDonald’s, snapper schools, world peace, woolly fleece, Ronald and raising beasts, chilly bins, cricket wins, fast skis, golf tees, silver ferns, kauri trees, Kiwi Burger that’s our tucker!

Yep: that guy.

Murray Grindlay’s story is not one of steady chart success, but rather of continual reinvention and of understanding the many ways music can embed itself in a culture.

Like more household names across the ditch, like Bon Scott, the Young Brothers, Jimmy Barnes, Johnny Farnham, Olivia Newton-John and many more, Murray Grindlay was born in the UK (Scotland, to be precise), but arrived in the Antipodes in his teens as part of the Ten Pound Pom migration wave. These lads often arrived in Australia with suitcases packed with the latest singles by the likes of the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and more. They helped transform a downunder music scene previously dominated by country music and local bands releasing covers of overseas hits.

One such band formed from this cultural fusion was Auckland’s Underdogs Blues Band. I first learned of this group’s existence when I picked up a battered LP from a trestle table at a Tasmanian garage band. I had no idea who they were, but a scan of the back cover had me hooked: local NZ band, mid-’60s, psychedelic blues. No way I was going to pass that up for a dollar (literally).

The Underdogs weren’t Grindlay’s first band – that honour belonged to an outfit dubbed the Soul Agents – but it was the band that first brought him a taste of such fame as was available in mid-’60s Auckland. With a soul-weary voice beyond his years and a charismatic stage presence, the Underdogs became a fixture on the Auckland club scene and NZ’s own pop TV show, C’mon. The Underdogs performed a mix of blues covers and originals, showcasing Grindlay’s gravelly vocals, the lead-guitar lines of Lou Rawnsley and only minimal backing from the rhythm section, bassist Neil Edwards and drummer Tony Walton. Their most popular song, “Sittin’ in the Rain”, was a lighter, poppier affair.

But by the mid-’70s, after returning to New Zealand from a stint in Australia, an on-stage run-in marked a change in Grindlay’s career and fortunes. During an Auckland gig, a couple of drunk gang members crashed the stage and smashed him in the face with a shot glass. After getting stitched up in Auckland Hospital’s ED, he decided to redirect his energy away from live gigs and towards composition and production. That decision opened the path to what would become his true métier: writing music for commercials, films and television.

Jingle writing is an often unfairly derided talent. As Australian underground rockers TISM wrote in their The TISM Guide to Little Aesthetics, “Give me a pop-song, mate. Give me a fucking pop-song. Not only is it more fun, it's pretty fuckin’ hard to write as well.” Brit music show The Old Grey Whistle Test took its name from a Tin Pan Alley rule-of-thumb: if they played a new song to London’s doormen in grey suits – the “old greys” – and the tune immediately lodged in their ears so that they could whistle it from memory, they had a hit.

So it goes with jingles. Just ask Alan Morris and Allan Johnston, collectively known as Australia’s Mojo jingle kings. There isn’t an Aussie of a certain age who can’t immediately reel off a chorus of C’mon Aussie, C’mon, Hit ’em with the Old Pea Beu, or I Can Feel a Four-X Comin’ On. Similarly, how many of you found yourselves singing along with the sample of Murray Grindlay’s jingles I listed at the start of this post? How many are still stuck in your heads?

It may not pack ’em out at the Albert Hall, but there’s a hell of a talent to writing tunes like that – and for 30 years, Grindlay was New Zealand’s ‘Jingles King’. His ability to work across genres – from country to swing, orchestral to rock – made him a natural fit for the advertising world and responsible for hundreds of tunes that filtered into the country’s collective memory. As well as “Have a Crunchie”, he penned “Welcome to Our World” for Toyota and the poignant “Dear John” song for BASF tapes. For many New Zealanders, Grindlay’s work became the soundtrack of daily life, encountered not on record players but between television programmes. He also worked with the uber-cool Stevie Ray Vaughan on the “Travellin’ On”, for the Europa oil company.

But he didn’t completely abandon the pop world. In 1977, he released a solo album, titled simply Murray Grindlay. The album is a gentle, laid-back collection of catchy country-rock ballads interspersed with rockier numbers and easy-going, island-influenced tunes.

Then in 1983, under the deliberately cheesy moniker and double-entendre-spinning spiv persona of Monte Video and the Cassettes, he released the infectious novelty pop hit “Shoop Shoop Diddy Wop Cumma Cumma (Wang Dang)”. The song reached number two in New Zealand and made the Australian charts, briefly granting Grindlay international recognition. A follow-up single, “Sheba (She Sha She Shoo)” and an accompanying Monte Video album followed, though they never matched the earlier success.

If nothing else, though, the venture showed Grindlay’s restless musical imagination, able to shift from blues shouter to pop satirist with apparent ease. Not to mention writing incredibly catchy pop songs.

His compositional talents also found a natural home in film and television. In 1977, he contributed songs to Roger Donaldson’s Sleeping Dogs, a landmark New Zealand political thriller that helped kickstart the country’s modern film industry. Nearly two decades later, he was co-composer with Murray McNabb of the soundtrack for Lee Tamahori’s Once Were Warriors. That score was notable not only for its emotional intensity but also for Grindlay’s use of Māori instruments such as the bullroarer, which added a haunting dimension to the film’s atmosphere. He would go on to contribute music to other productions, including Broken English and the television series Greenstone, proving his ability to adapt his craft to narrative storytelling as much as to commercial hooks.

Grindlay also became involved in production, producing the star-studded 1986 charity single “Sailing Away”. Promoting New Zealand’s America’s Cup challenge, the song became a national phenomenon and topped the charts. Later, he produced Goldenhorse’s second album Out of the Moon, helping to shape one of the most successful New Zealand pop acts of the early 2000s. His studio nous, combined with his deep understanding of audience appeal, made him a sought-after collaborator.

In the end, if Grindlay’s name is not always instantly recognisable to the general public, his music certainly is. His jingles in particular occupy a strange cultural space: brief, disposable by design, yet often remembered decades later. They testify to his gift for melody and his ability to distill ideas into instantly memorable hooks. In 2012, the advertising industry recognised this contribution with the Axis Lifetime Achievement Award, acknowledging that his work had not only sold products but also become part of New Zealand’s cultural fabric.

Perhaps most importantly, his work shows that music’s power is not confined to the charts or the stage: it can resonate just as powerfully when it slips, almost unnoticed, into the rhythms of everyday life.