Table of Contents

The Cold War American military presence in Europe has a surprising nexus with rock’n’roll. Elvis famously did his military service in Germany, while ’70s soft-rock band America met when their fathers were stationed in London with the USAF.

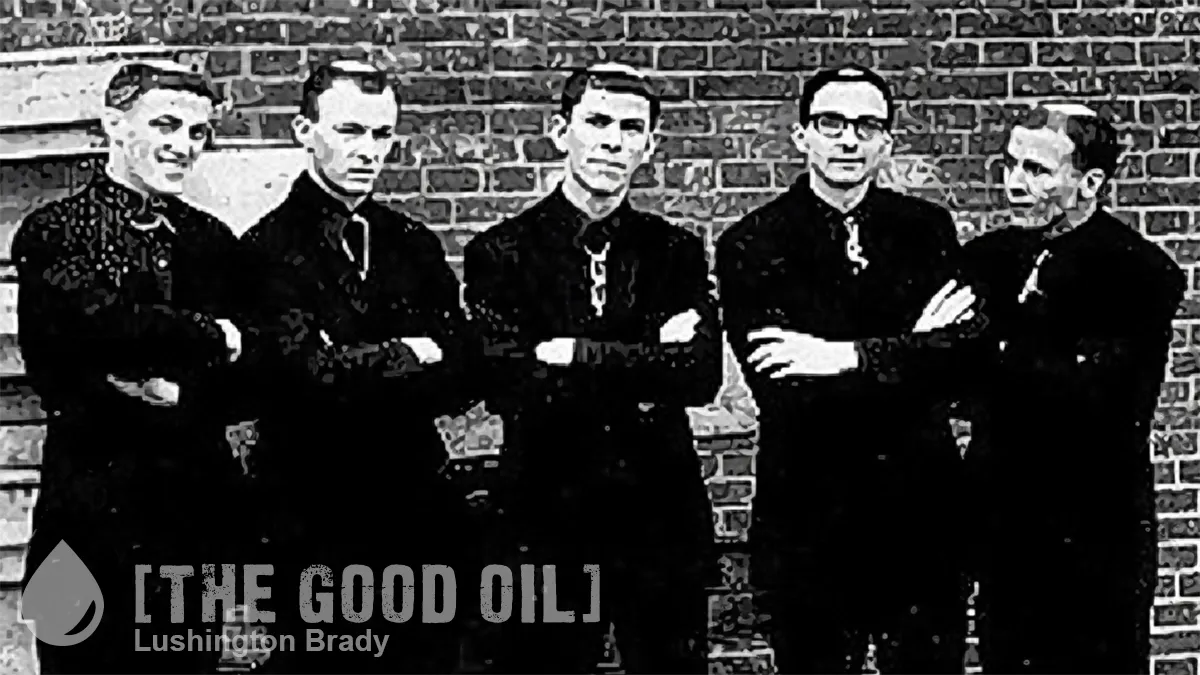

And in 1964, five American GIs stationed in Germany formed a band, initially called the Torquays then the Monks. For the next three years they pumped out a then-innovative style of rock’n’roll with heavy emphasis on percussion and rhythm over melody, distortion, banjo, shrill vocals and snarling lyrics (“Hey, well I hate you with a passion, baby. Yeah, I do. But call me.” Even their look was guaranteed to baffle mid-’60s audiences: black habits with cinctures tied around their necks, and their crowns shaved into Roman tonsures.

People stared at us, thinking we were monks, but then we talked and acted so rough. Young people would not look us in the eye. They would look away when we talked to them. Old women loved us, until they realized that – wait a minute, these guys are not nice monks!” Some people hated us – Thomas Shaw, the Monks.

As Marty McFly would say, guess the world just wasn’t ready for that yet – but a small group of the cognoscenti among their kids were gonna love it. Beginning with early ’70s krautrock through to punk, an influential mini-circle of musicians came to regard the Monks as unsung, pioneering geniuses. Kind of even-more obscure The Velvet Underground & Nico.

The origins of the Monks go back to late 1963, when four GIs stationed in Gelnhausen, Germany, form a band then called the Torquays (inspired by the Fireballs’ instrumental track of the same name). The lineup was Gary Burger (lead guitar, vocals), Larry Clark (organ), Thomas “Eddie” Shaw (bass guitar) and Dave Day (rhythm guitar). Initially, a West German known only as Hans filled in on drums, before the band recruited Roger Johnston, whose frenetic jungle drums would become the bedrock of the band’s sound.

The Monks began playing to the same kind of rowdy crowds who had nurtured the Hamburg-era toughness of the early Beatles. “We called it the Saturday night fights,” recalls drummer Eddie Shaw. “Because after the GIs would drink too much, there would be fights over the few girls who came there. Larry always brought his gas mask because the military police would come in and throw tear gas grenades to break up the fights. It was quite an experience.”

The Monks responded with an increasingly louder, dissonant, “steamroller of sound”. They also experimented wildly, but not always with success. “A lot of the experiments were total failures and some of the songs we worked on were terrible,” recalled lead guitarist Burger. “But the ones we kept felt like they had something special to them. And they became more defined over time… It probably took us a year to get the sound right.”

Two elements became key to the Monks’ sound: rhythm and feedback.

“We got rid of melody…. Everything was rhythmically oriented. Bam, bam, bam. We concentrated on over-beat,” says bassist Eddie Shaw. “The only time cymbals would be used would be for accent.” Drummer Roger Johnston was initially heavily influenced by jazz, but gradually dropped complex fills in favour of that pulsing ‘bam-bam-bam’ beat. Using bigger sticks and substituting heavy thumping on the tom-toms for cymbal flourishes. “I dogged it. I wanted it to sound as raw and thumping as possible,” Johnston said.

Bassist Eddie Shaw was also initially a jazzophile, with a strong musical heritage. “My great-uncles were well known gospel musicians in the 1930s and early 1940s (The Stamps Quartet). They wrote religious songs that are still played and sung in some churches today. Elvis Presley talked about them being a great influence on his music… When I was a boy the famous Bob Wills Western swing band, the Texas Playboys, used to come to my house when they were finished playing.”

Shaw began playing drums at 10 and by 15 landed his first professional gig, playing trumpet in a Dixieland band. Wayne “Mr Las Vegas” Newton, then all of 12 years old, was playing the same club on a different stage. On meeting the rest of the Monks, Shaw put away his trumpets and drums and took up the bass.

The other key Monks element, feedback, came about via a serendipitous bathroom break. “We were practicing and I had to take a leak,” Burger said. “I laid the guitar against the amp and walked off the stage. I forgot to turn it off and the thing began to make this god-awful racket. It started off humming and then it increased in volume. Roger started hitting his drums and it sounded so right together.” Shaw describes it as, “Just imagine the sound of the Titanic scraping along an iceberg. It was like discovering fire.”

The Monks may have discovered fire, but they might as well have discovered atomic fission in the Stone Age: they were just too far ahead of their time. Even Hamburg, epicentre of Western decadence in the mid-’60s Cold War, was perplexed by these strange, black-clad, shaven-headed Americans pumping out a raw, primal sound.

“Some of them loved us,” recalled Burger. “But others... Well, they didn’t have a clue what was going on. I think the image confused them as much as the music. We were a freak show to them.”

“Some people told us we didn’t look real,” says Shaw. “Walking through a crowded nightclub, I could feel people touching my head to see if everything was indeed real.”

The band’s first and only album, Black Monk Time, was released in 1966 by Polydor records. But Polydor refused to release it in the US, believing it “too radical and non-commercial”. Lyrics criticising the Vietnam War (“Monk Time”) didn’t help. A punishing six-month tour of Germany and Sweden, and limited chart success in Germany only, strained relationships in the band, as did heavy drinking, love triangles and resorting to speed to keep up the schedule. A planned tour of Vietnam was aborted when Johnston became convinced the band would be set on fire by the Viet Cong, in similar fashion to self-immolation protests by Buddist Monks.

The band disbanded in September 1967.

But, despite Polydor’s refusal to release Black Monk Time in the US, cassette bootlegs began to filter into the States by the 1980s. Successive generations of musicians began to listen. Acts such as the Dead Kennedys, the Beastie Boys, the Fall and the White Stripes all cited the Monks as influences. That influence filtered to such wildly disparate genres as punk, hip-hop and alternative rock.

Black Monk Time has become a heavily sought-after collectible. Copies of the original issue fetch up to $5000, and never less than $1000. CD reissues brought the band’s sound to new audiences. “I Hate You” was featured on the soundtrack of The Big Lebowski and a tribute album, Silver Monk Time, was released in 2006.

The band reunited periodically from 1999 to 2007. Roger Johnston died of lung cancer in 2004. Reunions of the surviving members took place in 2006 and 2007, before they officially disbanded in 2008. Dave Day died of a massive heart attack in 2008, while Gary Burger succumbed to pancreatic cancer in 2014.