Table of Contents

Valerie Check

Valerie Check is an energy and environmental policy intern at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy.

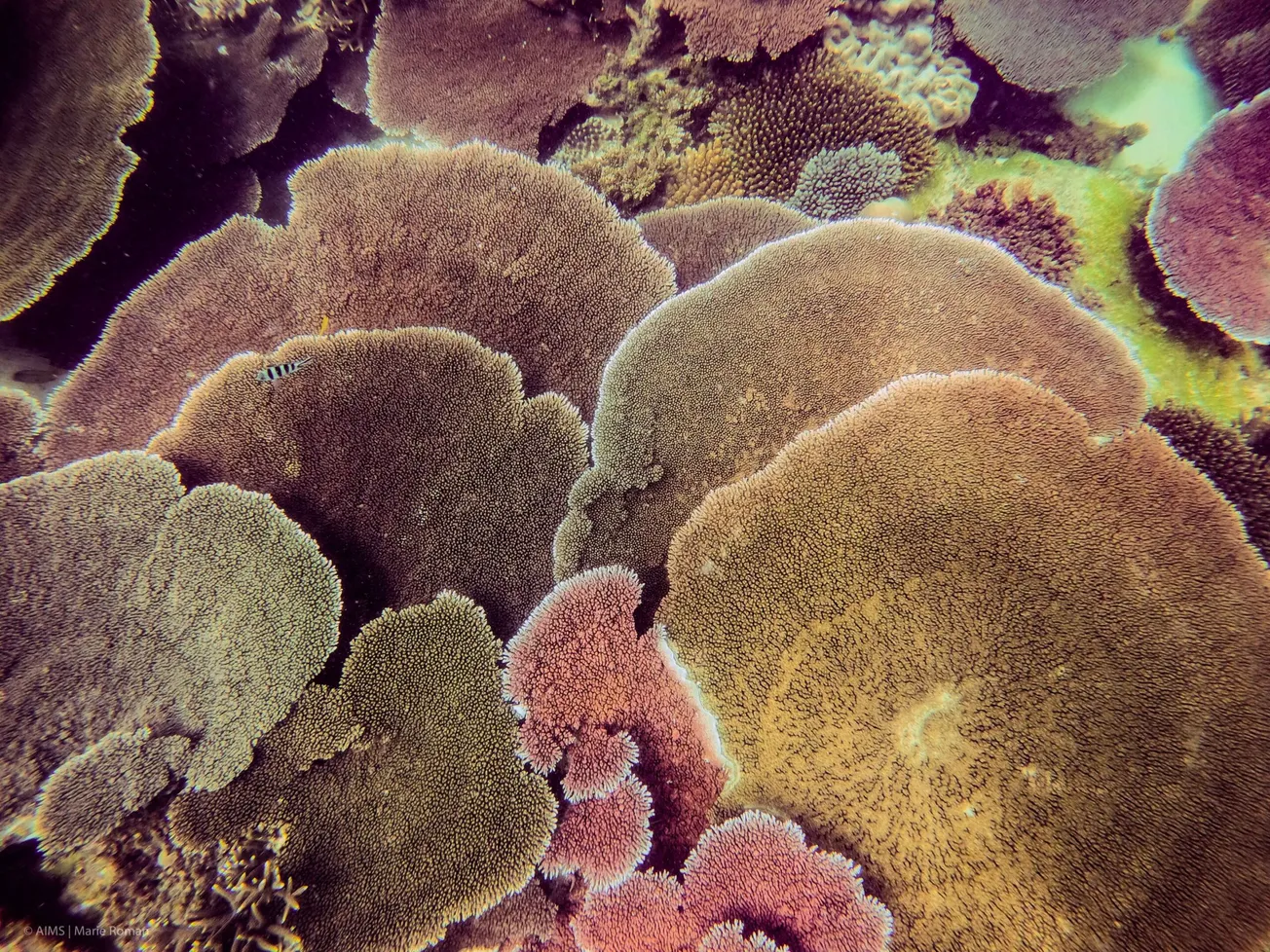

“More than half the world’s reefs have perished in the past 30 years,” Newsweek announced in an article claiming that ocean warming is driving bleaching events that have devastated reefs around the globe. Bleaching, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, occurs when coral tissue expels algae, causing the coral to turn white.

“There is at least a reasonable expectation that if current carbon dioxide emission trends continue, corals will not survive this century,” Ken Caldeira, a senior scientist with the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology, told USA Oceana.

Climate change advocates like Caldeira say that CO2-induced warming has driven an increase in the frequency and magnitude of bleaching events since the 1800s. This claimed rapid change suggests coral reefs are reaching a tipping point, “after which runaway climate change intensifies beyond humanity’s ability to arrest it,” according to Seaver Wang of the Breakthrough Institute.

Are these dire pronouncements accurate? Could a two-degree change in water temperature knock out a species that has survived for more than 40 million years?

Research evaluated by CO2-science.org, an organization that publishes weekly reviews of peer-reviewed scientific journal articles, shows “little evidence for climate change affecting reefs in a linear fashion.” The climate has warmed before, but reports linking reef expansion and decline to climate change fail to explain why previous temperature changes have not caused reef transformations similar to those happening now.

“Previous analyses failed to find any significant cross-correlation between changes in [the partial pressures of] CO2 and changes in reef attributes,” said Wolfgang Kiessling, a German researcher, and professor at Friedrich-Alexander-University of Erlangen-Nürnberg. Kiessling’s research shows that increases in atmospheric CO2 and water temperature fail to explain reef changes throughout history.

Corals have survived warming and also recovered from widespread bleaching events over the past 400 years. A 2015 study conducted by UCLA researcher Ruth D. Gates and California State University researcher Peter J. Edmunds called bleaching an adaptive mechanism. The diversity of corals provides them the opportunity to shuffle symbiont genotypes or to replace one species of cooperative algae with another species that resists either cold or heat, as needed. A 2001 study found that “coral bleaching can promote rapid response to environmental change” by making development in coral communities work better. The study concluded that coral bleaching may “help reef corals to survive” the potential stress of temperature changes.

In 1996, 1998, and 2002, the Arabian Gulf suffered from high-frequency temperature-related bleaching events. Acropora, a small polyp genus of stony coral, experienced the fastest bleaching and the highest mortality of all coral varieties reviewed in 1996 and 1998. But in 2002, Acropora bleached less than all other corals. This improved survivability suggests that the coral found a way to adapt to warmer conditions.

A model made in 2018 by a team of American and Australian researchers corroborates this research. They combined genomics with biophysical and evolutionary modelling and found that coral populations are able to “successfully adapt to changing temperatures” along the Great Barrier Reef. This, researchers say, should allow coral reefs to survive comfortably for at least another century.

Corals have also demonstrated an ability to shift and expand their range, helping them remain in ideal water temperatures. Reachers who used 80 years of national records from the temperate areas of Japan concluded that four out of nine studied coral species showed poleward expansion at up to 14 kilometres, or about nine miles per year, since the 1930s; this is significantly faster than is the case with other species. The other five species researchers looked at remained stable without shrinkage or extinction. Mature coral colonies in the expanded areas also exhibited spawning, which indicates their potential to widen their range even further. If corals in tropical areas suffer declines due to rising water temperature, they may simply shift to more temperate areas.

Though corals have several tactics to tolerate a warmer climate, temperature change is not their only threat. One significant challenge is eutrophication, or nutrient pollution, caused by fertilizers from agricultural runoff. But as previous Mackinac Center research concluded, “Addressing agricultural runoff is complicated, and there is no simple fix.”

Coral health is a legitimate concern. Coral reefs are home to over 25% of all marine life, containing one million aquatic species, which include over 4,000 species of fish alone. Reefs are reported to contribute $29.8 billion to the global economy each year, and an estimated one billion people depend on coral reefs for food, income, and flood protection.

When considering solutions to eutrophication, it is important to remember the benefits synthetic fertilizers have on crop growth and food security. Stopping fertilizer use entirely to promote healthy coral reefs would increase food prices drastically, leaving consumers paying roughly $2.9 billion more each year. It is possible to reduce fertilizer runoff while still increasing food production, thus helping the environment without harming humanity.

Though Caldeira and other researchers say coral reefs are in grave danger from fossil fuel-induced warming, research shows that reefs are durable. Their ability to adapt to changing conditions gives us confidence in their continued future health.

This article originally appeared at Mackinac