Table of Contents

It was Longfellow’s Psalm of Life that coined the phrase “footsteps on the sands of time”:

Lives of great men all remind us

we can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time.

But it needn’t be only “great men”, generals, kings, and prophets, who leave footsteps on the sands of time. Even the humblest, not even quite men, could leave behind literal footprints. Such as sets of fossilised hominin footprints along South Africa’s coastline.

The study of these fossil tracks and traces is called ichnology.

I am an ichnologist. In 2008 my colleagues and I launched the Cape South Coast Ichnology Project to study a 350km stretch of South Africa’s coastline. We’ve since identified more than 350 vertebrate tracksites, most of them in cemented dunes called aeolianites that date back to the Pleistocene Epoch (also known as the Ice Age), which began about 2.6 million years ago and ended 11,700 years ago.

It’s often not grasped just how rare fossils really are. As one paleontologist puts it, winning the lottery on odds of one in seven million is a sure thing next to the chance of an organism becoming a fossil. Fossilised footprints are orders of magnitude rarer.

At a global level it is rare to find fossilised hominin tracks. There is something very special about them: a fossil trackway looks as if it could have been created yesterday, and the fact that our own ancestors would have created such tracks fills them with extra meaning. It’s always a thrill for researchers to find them.

South Africa is astonishingly lucky in its beaches being a global hotspot for fossilised hominin footprints.

We knew from the region’s extensive archaeological record that ancestral humans inhabited the region during the Pleistocene. And Homo sapiens tracks had been identified elsewhere in South Africa, on the Cape east coast in the 1960s and the Cape west coast in the 1990s. But, given their rarity, we weren’t banking on hominin tracks being among our finds.

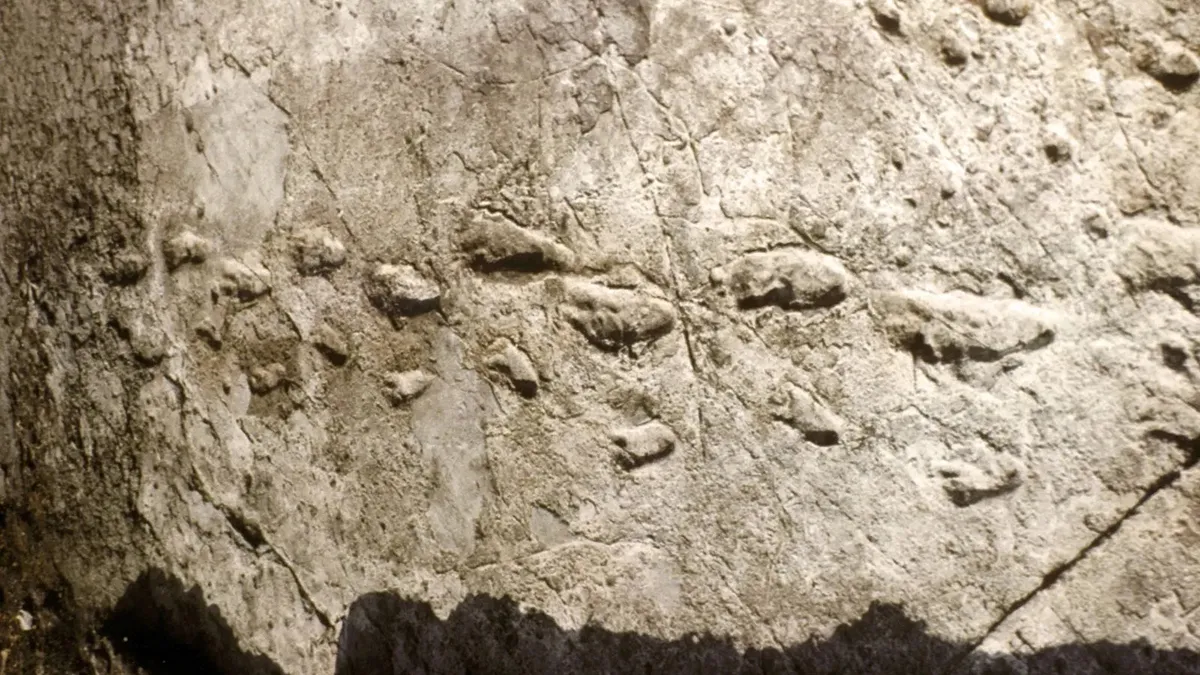

We were fortunate. In 2016 we found 40 hominin tracks on the ceiling and side walls of a cave at Brenton-on-Sea, near the town of Knysna on the Cape south coast. In subsequent years we have been privileged to find more hominin tracksites, all on aeolianite surfaces on the Cape coast. One discovery, in the Garden Route National Park, even included the oldest Homo sapiens footprint identified anywhere in the world – it dates back about 153,000 years.

Now we’ve documented a cluster of nine hominin trace fossil sites at Brenton-on-Sea: seven tracksites, and two open-air archaeological sites containing tools, shells and bone (which help us understand the diet of our ancestors).

What can fossilised footprints tell us? Among other things, the likely height and weight of those who made them. One set of tracks in Australia suggest a runner whose burst of speed on the hunt would be the envy of modern Olympians.

Three of the Brenton-on-Sea sites also contain some of the oldest known evidence of humans using sticks. The organic matter from which such sticks were composed would long since have decayed, and the ichnology (trace fossil) record therefore provides what is probably the only viable means of identifying such stick use.

Sticks could potentially have been used as walking or running aids, to cope with ambulating with an injury, in foraging techniques, for messaging, or for what might be aesthetic purposes, such as inscribing patterns in the sand.

It’s a charming image: an ancient adult and child, walking along the beach, with one of them using a cool stick they’d found to doodle patterns in the sand.

Some things about human nature never change, it seems.