Table of Contents

Good governance involves a clear unbiased investigation and consideration of all the aspects of a situation. This involves open debate, a willingness to listen and to be able to consider aspects that one may not have thought about beforehand. When every side of the issue has been fully canvassed and discussed, opposing views heard and the various factors weighted accordingly, a consensus decision can be reached.

That is good governance. A knee-jerk reaction is quite a different beast and is always bad governance. As they say: decide in haste, repent at leisure. The completely ridiculous performance by the government over the rushed gun law legislation is a great example of bad governance.

Lawyer and ex ACT MP, Stephen Franks, raises some interesting points in a recent blog post.

Quote.When the Treaty was signed, pu and tupara (muskets and double barreled [sic] shotguns) were among the most valuable of all taonga under Article 2 (if it really does go beyond the real property interests listed as the New Zealand courts say). Article 2 assured the chiefs and all the ordinary people of New Zealand that they would have undisturbed exclusive use and possession of their taonga.

So if relations between Police and (rural) Maori break down, it is inevitable that some Maori will assert a Treaty right to be free from confiscation and possibly even licensing for firearms.

Urban judges from leafy suburbs will look for some sophistry to reject that claim both in law, and morally. But they should not underestimate the power of a strong view that authority is wrong allied to a wide belief in historical right. We have seen that repeatedly. Myth becomes political reality when enough people believe the myth.End quote.

The Arms Act 1860 exempted Maori. * I have not researched the history, but I suspect that reflected both practical common sense on enforcement, and recognition of a Treaty assurance of Maori rights to retain pu and tupara. Under the so-called right of development in Treaty jurisprudence, that would now extend to whatever is the modern equivalents (in relative effectiveness to other weapons?)

I raised this possibility in my last minute submission to the Select Committee. I imagine there will have been many, judging from the latency on the Parliamentary website template for submissions.

Irrespective of the strength of the possible treaty argument, a heavy handed law change that rural people see as unreasonable could have a high price.

I have been a hunter for 50 years. I have a large rural property. I know hundreds of fire-arms users. I was unconcerned by a move against genuine MSSAs and large capacity magazines. But the Bill goes much further.

Parliament will be largely unaware of the level of informal borrowing and use of firearms in rural communities, particularly among Maori, that occurs with indifference to current law let alone what is in the Bill.

I can attest from personal knowledge to the degree of non-compliance with law on registration of vehicles, and driver licencing. There is similar non-compliance with gun owner licence requirements.

I believe that the Police wisely avoid interfering where they feel there is likely to be no harm done. And with positive relationships, unless forced to act, they get cooperation and information from families that would be at risk if there was vigorous inspection or enforcement.

But Police will have little alternative but to enforce the new law, though thousands of gun owners could decide to ignore it, or worse, to hide their guns, or to offer them to relatives or others who will be willing to ignore the law change. Those firearms will become invisible, whereas at present, the Police can expect reasonable frankness about them.

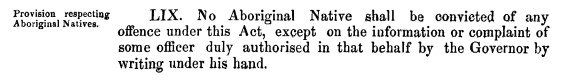

* Mr Franks is a lawyer, I am not, but the Act does not appear to exempt Maori (or ‘Aboriginal Natives’ as they were referred to.)

If the right person laid the complaint then they could be convicted. This is the only clause that mentions Aboriginal Natives, apart from the definition of same at the start of the Act.