Table of Contents

Michael Cook

Michael Cook is the editor of MercatorNet. He lives in Sydney, Australia.

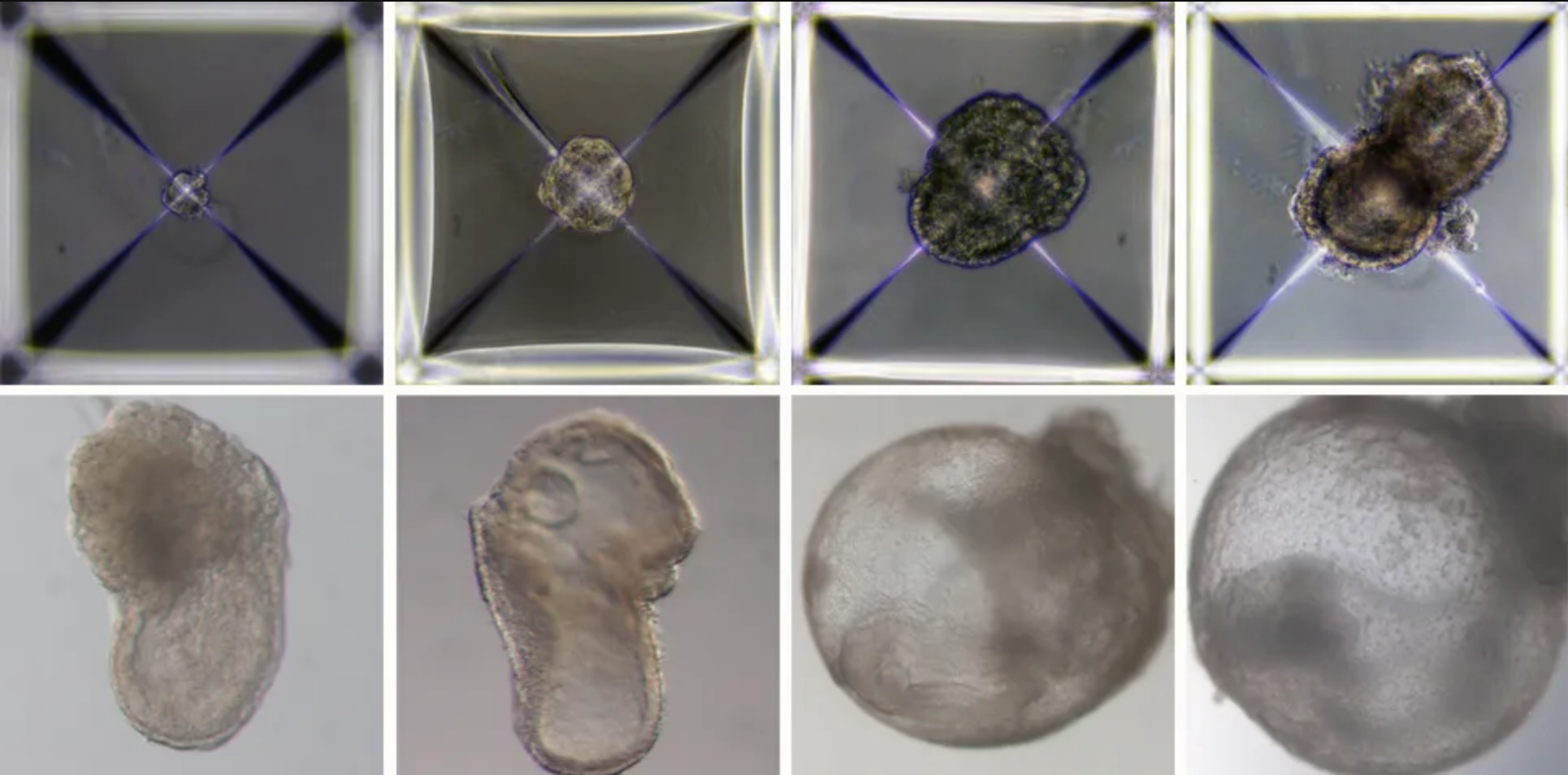

Israeli scientists have created the world’s first “synthetic embryos”. They used mouse stem cells to create embryos, nurtured them in an artificial womb and grew them for 8½ days – roughly the equivalent of three weeks of a human pregnancy.

Their research, which was published in the journal Cell last week, is being acclaimed by scientists as a ground-breaking development. Inside the tiny mouse embryos, the researchers can see organs developing. “We view the embryo as the best 3D bio printer,” Jacob Hanna, a biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science, told MIT Technology Review. “It’s the best entity to make organs and proper tissue.”

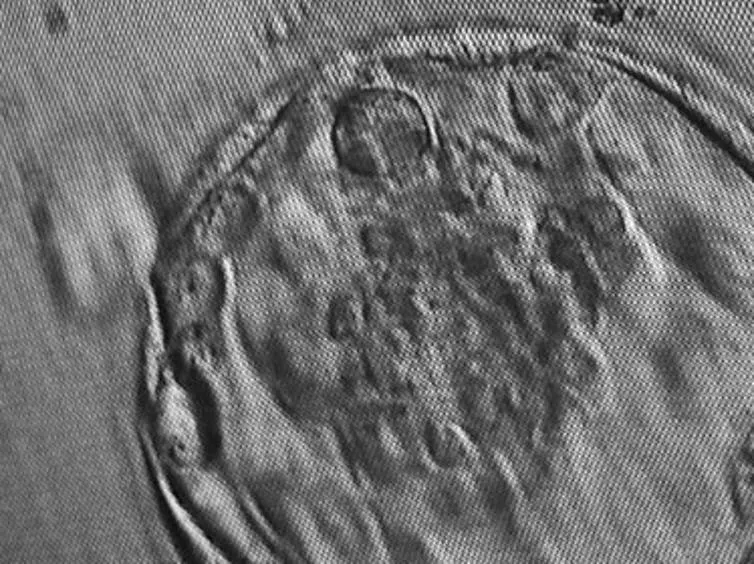

The mouse embryos developed beating hearts, flowing blood, intestinal tracts and cranial folds in the brain – even though they were created from scratch in a Petri dish.

“This experiment has huge implications,” says Bernard Siegel, of the World Stem Cell Summit, a group which lobbies for regenerative medicine. “One wonders what mammal could be next in line.”

All going well, the next mammal is going to be homo sapiens.

Dr Hanna’s ambitions are immense. The ultimate goal of his start-up company, Renewal Bio, is “to make humanity younger and healthier by leveraging the power of the new stem-cell technology” to solve ailments such as “infertility, genetic diseases and longevity”.

He believes that there will be a huge market for products derived from synthetic human embryos.

Since the turn of the century, developed nations have seen a clear trend: declining birth rates and fast aging populations. With significant socioeconomic implications, this trend threatens to upend health systems, retirement programs, and workforces across the globe. At the beginning of life, this is shown by a 5-10 per cent increase in infertility treatments by US couples each year. Towards the end of life, these issues are manifesting in fast-aging populations that balloon healthcare costs. In the US, the aging population is driving national health expenditures to increase at a rate of 5.5 per cent per year, and are expected to reach more than $6 trillion annually by 2027.

The vision of the company is ‘Can we use these organized embryo entities that have early organs to get cells that can be used for transplantation?’ We view it as perhaps a universal starting point.

What he has in mind is projects like rebooting the immune system for the elderly by creating blood from an embryo. Or growing a female embryo until the gonads form and the eggs can be harvested. In other words, Dr Hanna and his colleagues want to strip-mine human embryos which have been custom-made for their clients.

They also claim that their method of producing “synthetic embryos” creates the placenta and yolk sac surrounding the embryo. This suggests that perhaps a baby could reach full term in an artificial womb with no need for a mother at all.

But would these “synthetic embryos” really be human? Hanna dismisses the idea. “We are not trying to make human beings. That is not what we are trying to do,” he told MIT Technology Review. “To call a day-40 embryo a mini-me is just not true.”

However, Dr Hanna is not a philosopher. He is just a talented technician tinkering with biological structures. Whether or not it is human is not his to decide. Even though the embryo has not been conceived naturally, it might grow into a human being if it were transferred into a womb.

At the moment scientists quoted in the media are insisting that “synthetic embryos” are definitely not embryos. As Australian stem-cell scientist Megan Munsie wrote in The Conversation: “They replicate only some aspects of development, but not fully reproduce the cellular architecture and developmental potential of embryos derived after fertilisation of eggs by sperm – so-called natural embryos.”

But even if this is true, Dr Hanna’s ultimate goal seems to be to create “synthetic embryos” which are as close as possible to “natural embryos”. If they are not human initially, might they become human later on, as the field advances?

With so many unknowns, the need for regulation of this new technology is urgent. And the ones writing the law should not be the same entrepreneurs who stand to become billionaires if their dreams come true. If the brief history of stem-cell science has taught us anything, it is that scientists’ lust for power always outruns their interest in ethics.