Table of Contents

The human hope of finding someone else to talk to springs eternal. For over 40,000 years, homo sapiens has been in the almost unique position of being the sole species of its genus on the planet. We’re also the only fully sentient species that we know of in the entire universe.

All that’s left us feeling a bit lonely, it seems. Once we invented fairies and other mythological creatures to try and have someone else to talk to. Now, we look for fairies on other worlds.

Without any luck, so far.

Mars, the great hope of finding life on other worlds, is proving a total bust. Far from hosting naked, busty wenches or even sacks of slime with tentacles, Mars has turned out to be a barren wasteland with not even a microbe or two to get our hopes up. Venus is even worse. The outer planets, great, radioactive balls of gas that they are, are even more unlikely.

In more recent years, attention has turned to the moons of the gas giants. After all, some of these moons are big enough to be worlds in their own right and, weird as it may seem, they just might have the conditions to sustain life.

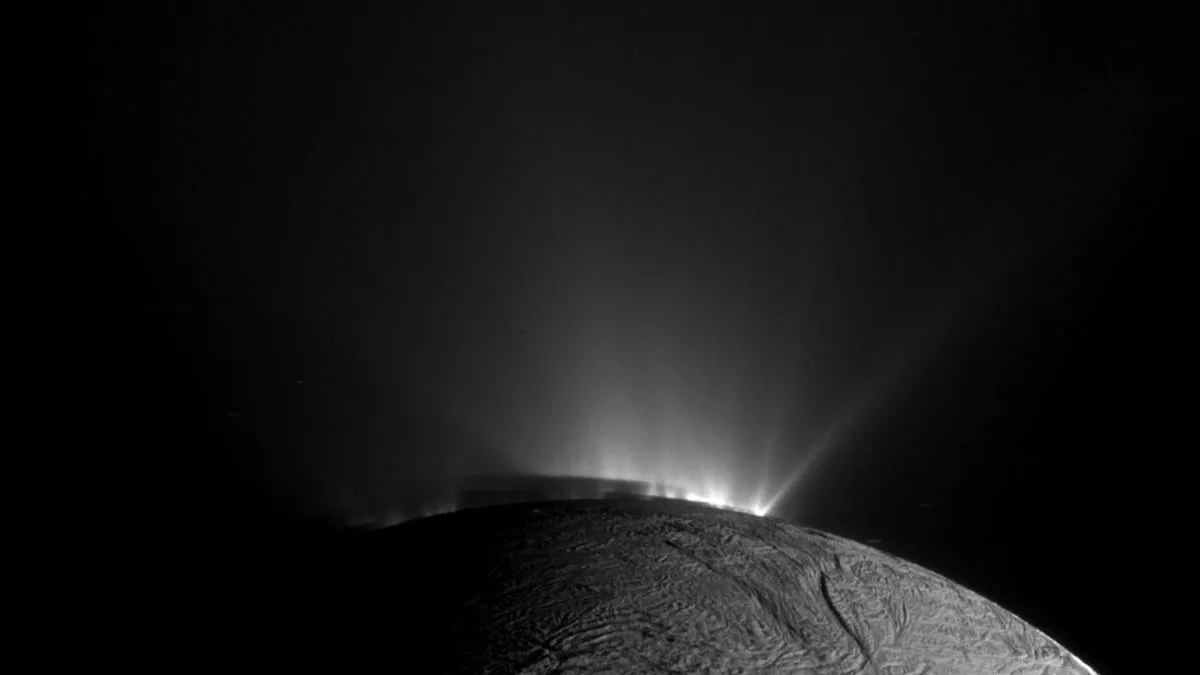

From space, Saturn’s moon Enceladus might not seem like a hospitable place for life. Its cold surface is caked thick with fresh ice, marked by craters and active cryovolcanoes that spew ice crystals. But scientists believe beneath that frozen exterior hides a salty liquid ocean. With energy from geothermal vents on the ocean floor, and a smattering of the right ingredients, it might just provide a place for life to evolve and take hold. A new analysis of data from NASA’s Cassini mission reveals that the moon has, in theory, all the chemicals it needs to support living things.

It’s been known since the first probes flew by in the ’80s that ice-balls like Enceladus might harbour liquid water, the holy grail for life-as-we-know-it, beneath their frozen surfaces. In 2010: Odyssey Two, Arthur C Clarke speculated that life might thrive under the icy crust of Jupiter’s moon, Europa.

But water is not the only essential for life. A slew of elemental chemicals also work to keep us life forms chugging along. As any crop farmer knows, phosphorus is one such essential element.

Plumes of water erupting from Enceladus contain phosphorus, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature by an international team of researchers. They found the phosphorus by examining data collected by the Cassini probe from its 13-year survey of the Saturnian system. It’s the first time this element – an essential component of being alive – has been found in an ocean not on Earth.

“Phosphorus in the form of phosphates is vital for all life on Earth,” says study author Frank Postberg, a planetary scientist at the Free University of Berlin. “Life as we know it would simply not exist without phosphates. And we have no reason to assume that potential life at Enceladus – if it is there – should be fundamentally different from Earth’s.”

Of course, fulfilling necessary conditions isn’t a guarantee.

The discovery does not provide any evidence for aliens on Enceladus. But the presence of phosphorus removes a major obstacle to any life that might evolve there. Previous studies had suggested Enceladus’s ocean might not contain any phosphorus, according to Postberg. This discovery changes how scientists must think about the moon’s potential habitability, and it may guide research on other icy moons with subsurface oceans, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa.

One such future research project may involve semi-autonomous underwater drones. Such machines are being tested right now. But the engineering challenges are a quantum leap up from current space probes. The greatest challenge is, of course, the sheer distance: a radio signal sent to a probe on one of Saturn’s moons would take nearly 10 hours to arrive. Two-way communication, at least 20 hours. Underwater being a much more dynamic environment than space, any such probe would necessarily have to be at least partially self-guiding.

Enceladus’s ocean is somewhat chemically different from Earth, according to Mikhail Zolotov, a planetary geochemist at Arizona State University and the author of a commentary on the study also published Wednesday in Nature. “In our ocean, it’s mostly table salt, like sodium chloride,” Zolotov says. On Enceladus, the salt is baking soda – the same stuff you’d find in a kitchen.

Plenty of marine Earth life could survive Enceladus’s waters just fine, according to [Morgan Cable, an astrobiologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory]. But if any life has evolved, or ever does evolve, on the icy moon, it’s likely to be microorganisms rather than the extraterrestrial equivalent of fish or whales.

That’s because there’s still one vital piece of the life puzzle that’s in short supply among the outer planets. And that’s directly related to the vast distances they are from the Sun.

That has less to do with the chemistry of the Enceladean ocean than the energy available there for life.

“On Earth the dominant energy source that all life uses, either directly or indirectly, is sunlight. You either photosynthesize directly, or you eat the plants that do it, or you eat the animals that eat the plants,” she says. Sunlight doesn’t reach the moon’s waters through its icy shell, so energy likely comes from geothermal sources – the structure of ice crystals caught by Cassini suggests the grains formed near geothermal vents on the ocean floor, where water meets a rocky interior.

“If you look at the net amount of energy that you get from that versus from sunlight, it’s orders of magnitude less,” Cable says. “That means you can either support a community of microbial cells, or you can have a handful of more energy-hungry organisms.” Enceladean whales are not entirely out of the question, but it would likely be “a lonely whale singing a sad, sad song all by itself”, she says with a laugh. “How terrible would that be?”

Popular Science

Ask we humans, who are so sad at being apparently alone in the universe that we’re willing to expend vast resources and efforts to try and prove that we’re not.