Table of Contents

For once, NASA has crashed a spaceship on purpose – and demonstrated a potentially humanity-saving technology.

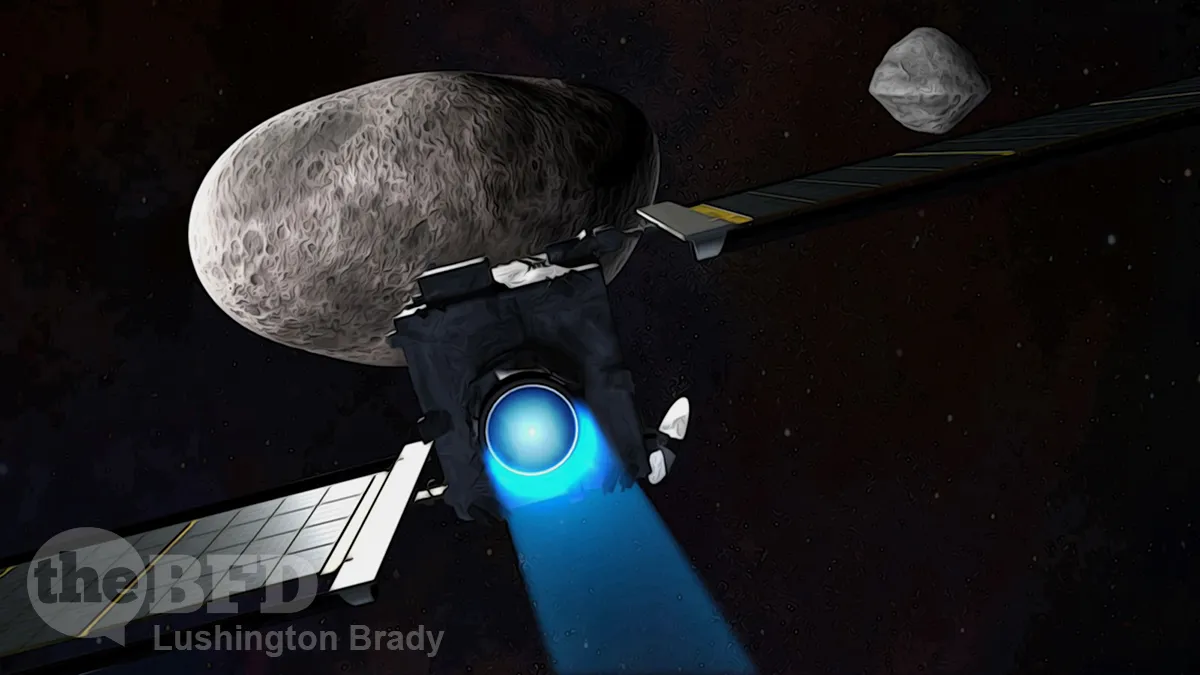

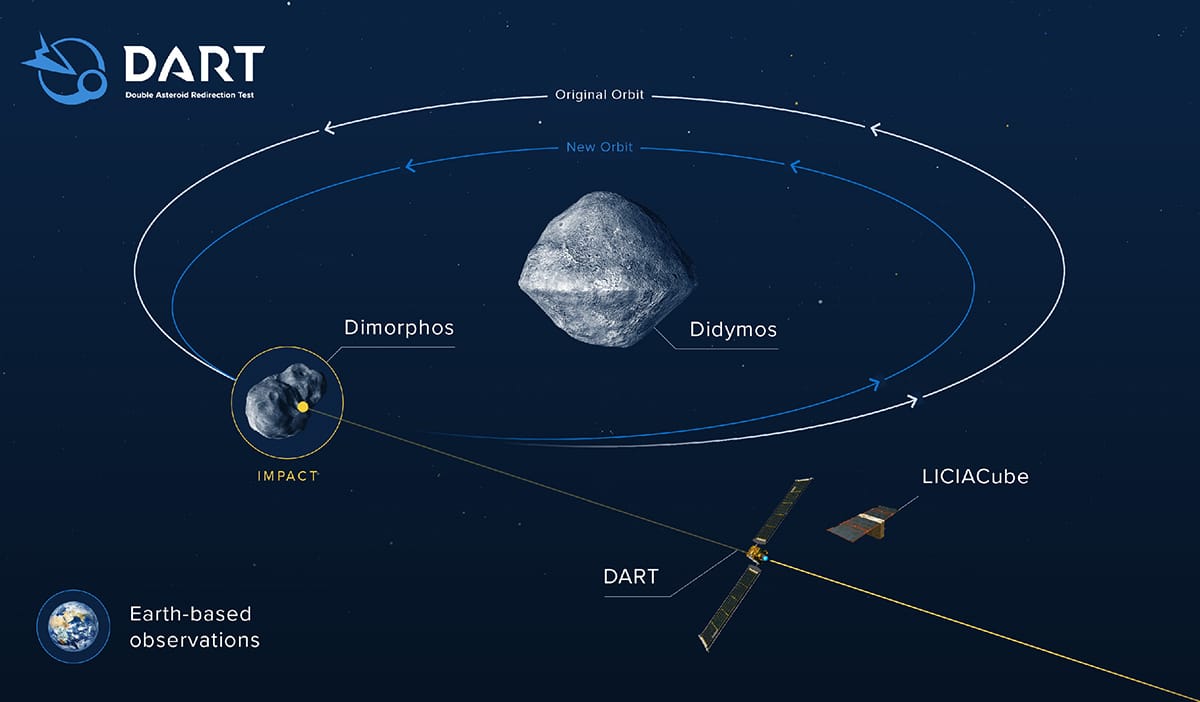

The spaceship in question was the DART mission: Double Asteroid Redirection Test. It’s the first practical test of what will form the basis of a planetary defence system against future asteroid impacts.

The test was successful beyond NASA’s wildest hopes.

NASA said the intentional collision between its uncrewed spacecraft and the 525-foot-wide asteroid, called Dimorphos, successfully shifted the asteroid’s orbit around a larger asteroid called Didymos.

Since the collision, DART team members have been working to quantify the shift in Dimorphos’ orbit. Before impact, it took Dimorphos 11 hours and 55 minutes to complete one orbit around Didymos. Now that time has been shortened to 11 hours and 23 minutes, [NASA Administrator Bill Nelson] said.

That 32-minute change is well above the 10-20 minute change mission scientists were hoping for. While it may not sound like much, it’s actually a pretty big deal.

The first thing that must be considered is sheer inertia of even a moderately massive celestial body. Dimorphos is around 150m in diameter, with a mass similar to the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Try to imagine shifting the Great Pyramid, and you’ll get an idea of what has been achieved.

The spacecraft was moving more than 14,000 miles an hour when it struck Dimorphos, which was about seven million miles from Earth at the time of impact and doesn’t pose a threat to our planet.

So, that’s 22,531 kph: 6,258 metres per second. At that velocity, the 570kg, vending-machine-sized spacecraft was packing quite a punch: 11,161 megajoules, or equivalent to nearly three tonnes of TNT.

The same conversions of mass and velocity to kinetic energy is what makes asteroid impacts so potentially deadly. Consider the difference between dropping a bullet on the floor at a couple of metres per second, and firing one at 1200 m/s from a rifle.

If an asteroid the size of Dimorphos were to strike a populated area, it could bring about a disaster “on the scale we’ve never seen before”, said NASA’s planetary defense officer Lindley Johnson.

There have been devastating asteroid strikes in Earth’s history, including the impact from a six-mile-wide [9.6km] space rock that played a role in the extinction of the dinosaurs more than 65 million years ago. In 2013, a roughly 60-foot-wide [18m] fireball exploded above the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, damaging thousands of buildings and injuring about 1,500 people.

Luckily, nothing the size of Dimorphos is known to be on a collision course with Earth within the next century. Known to be. Only an estimated 40 per cent of asteroids and comets whose orbits come close to Earth’s have been found and tracked.

It’s the unpleasant surprises that we have to watch out for.

Fortunately, the DART mission has demonstrated a potentially humanity-saving principle. Even a spacecraft the size of a vending machine can change the orbit of a decent-sized asteroid. Even if by a little bit.

But a little bit can add up to a lot, over cosmic distances. Enough, for instance, to divert a deadly asteroid onto a safe course.

All it takes is some basic physics and something handy to throw at it.

[NASA’s Planetary Defense Officer Lindley Johnson] said there are alternatives to the kinetic-impactor technique successfully demonstrated by the DART mission, including shooting asteroids with ion beams or changing their trajectories through the use of a so-called gravity tractor – a spacecraft that looms near an asteroid and exerts a gravitational pull on the space rock for an extended time.

The Australian

In the meantime, humanity has at least one ace up its sleeve.

Missions such as DART offer potentially massive returns at relatively small cost. Perhaps we’ll never need to use such a device in practice – but it’s better to have it and not need it, than to need it and not have it. The difference could be literally existential.