Table of Contents

Amanda Reilly

Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

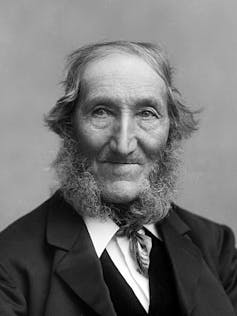

When Wellington carpenter Samuel Parnell began the struggle for an eight-hour working day back in 1840, he could have never foreseen how modern work culture would evolve. But he would no doubt empathise with the challenges faced by today’s workers.

History tells us that Parnell, recently arrived from London, agreed to take a job building a store on the proviso he only work eight hours a day. He reportedly told his would-be employer:

There are twenty-four hours per day given us; eight of these should be for work, eight for sleep, and the remaining eight for recreation and in which for men to do what little things they want for themselves.

Given the scarcity of carpenters at the time, there wasn’t a lot of bargaining and Parnell was granted his wish. The idea gained momentum, with a meeting of Wellington workmen later that year resolving to work from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.

They also agreed that anyone offending against this principle would be ducked in the harbour – one way of ensuring solidarity perhaps. The principle of an eight-hour day was picked up by various union campaigns, and over time achieved some recognition in law.

More than 180 years after Parnell made his stand, New Zealanders largely take the celebration of Labour Day for granted. But those able to enjoy the coming long weekend might also pause to reflect on what has happened to the eight-hour day in an era of constant digital connection and being “always on”.

Constant connectivity

When Samuel Parnell left work each day, neither his employer nor or his co-workers could contact him. Before any real rapid communications technology, let alone cell phones or email, he had no reason to contemplate the need for a “right to disconnect”.

But our modern, digital work lives raise serious questions about how we reconcile the demands of work with the need for rest, recreation and family life. How do we limit after-hours contact to maintain a boundary between work and non-work time?

As expectations of constant connectivity and accessibility have increased, that boundary has blurred for many workers. Research has shown how significant after-hours work communication creates high stress levels, and long working hours are a health hazard that can even lead to premature death.

New Zealanders generally work more hours than their OECD counterparts. And there is research that suggests the pressure to always be online is driving burnout around the country.

A growing movement

For all that, the regulation of working time in New Zealand is relatively rudimentary and non-prescriptive compared to other jurisdictions. It is covered by section 11B of the Minimum Wage Act, which says employment agreements should be fixed at no more 40 hours a week unless both parties agree to more.

Occupational health and safety law requires both employers and workers to take all practicable steps to ensure health and safety in the workplace, including a responsibility to manage fatigue.

But there is no statutory right to disconnect, even though the concept has been gaining traction overseas.

It was first proposed in France in 2013, with a national agreement encouraging businesses to specify periods when work communications devices should be switched off. This became law in 2017, regulated by a “Droit à la Déconnexion” (right to disconnect) article in the Labour Code, which refers to the need for “respect for rest, personal life and family”.

Several European nations followed France’s lead, and other countries (including Kenya, India, Argentina, and the Philippines) have either implemented, or are considering establishing, such a right.

Early forms of regulation have been relatively light, simply requiring employers of a certain size to have a policy, or to consult with worker representatives about developing one.

But more prescriptive law is emerging. In Portugal, for example, employers must not contact employees outside working hours, except in emergencies. There are sanctions available if employers transgress.

New Zealand lagging

It isn’t only governments looking into a right to disconnect. Following the example of the Victorian Police, some of Australia’s biggest trade unions are now bargaining to have the right included in enterprise agreements.

In the private sector, some progressive companies (including in New Zealand) are beginning to get on board, voluntarily implementing their own policies.

But despite New Zealand workers being among the first in the world to fight for and claim the eight-hour working day, the right to disconnect has not appeared anywhere on the local policy horizon. It’s a conversation the country should have.

In the meantime, there are small steps we can take as individuals – starting with making work emails outside of working hours the exception, rather than the rule.

It might not change the world overnight. But if enough people join the movement, it could lead to a healthier work-life balance for everyone. Samuel Parnell would surely approve.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.