Table of Contents

A couple of years ago, I wrote about Zealandia for the BFD. Zealandia is the name given to what was the world’s eighth continent, until it sunk beneath the Pacific, like the fabled Lemuria. Today, all that remains above the waves are its once-highlands, now islands, such as New Zealand and New Caledonia.

The first hints that there even was a real lost continent began to emerge in the early 2000s, thanks to satellite gravity measurements of the Earth’s crust. Its outlines were mapped in 2002, and Zealandia was officially recognised as a continent in 2017.

Recent research has mapped it in greater detail than ever.

This month, an international team of researchers released the most detailed maps of Zealandia to date – incorporating all five million square kilometres (two million sq miles) of this underwater region and its geology. In the process, they have uncovered hints as to how this mysterious continent formed – and why it has been obscured beneath the waves for the last 25 million years.

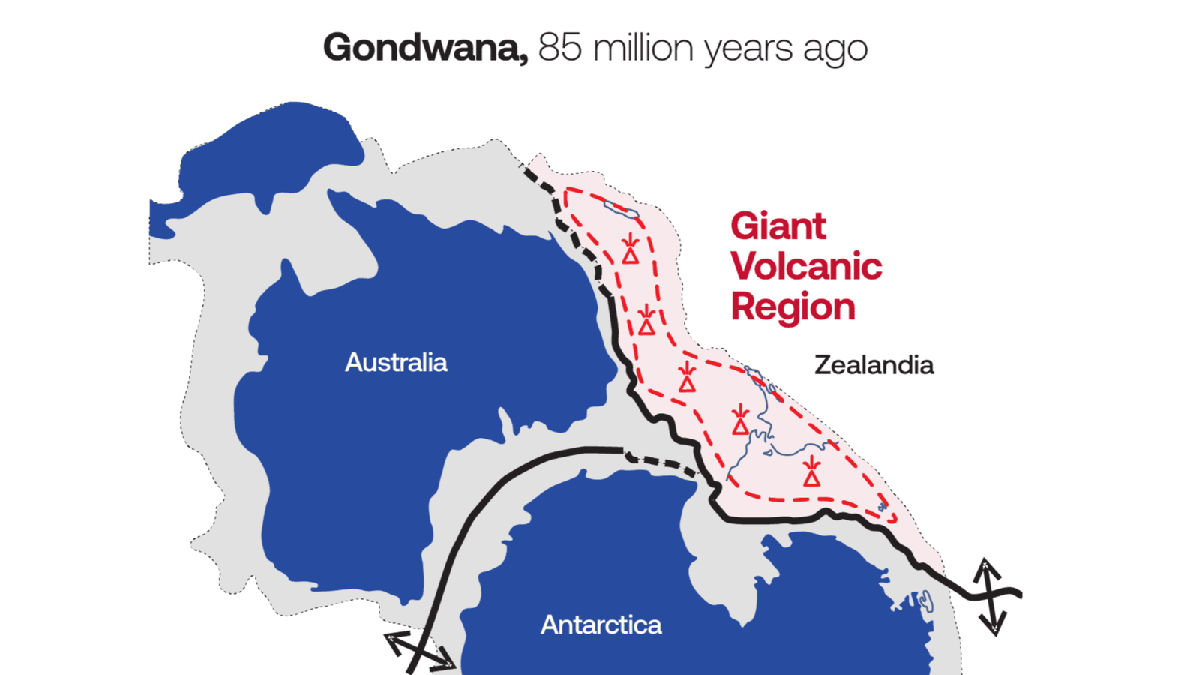

Like Australia, Antarctica, India, Africa and South America, Zealandia formed when the supercontinent of Gondwana began to break apart. As the new continents drifted apart, Zealandia struck out on its own into the Pacific, existing for tens of millions of years as an island-continent. But, by 25 million years ago, most of it was underwater.

This is partly because of a strange event that occurred when it split from Gondwana.

In 2019, an international team of scientists mapped the geology of South Zealandia […] For the latest study, another research group – involving many of the same geologists as before – charted North Zealandia.

This time, they analysed rocks that had been dredged up from the Fairway Ridge, a region of the South Pacific off the coast of Australia, which forms the northernmost tip of Zealandia. These ancient remnants, which have not had a dry day for 25 million years, included a mixture of igneous rocks – those formed by volcanic processes – and sedimentary ones made in shallow basins just off the coast of Zealandia.

Using a variety of techniques, including radioactive dating, scientists were able to estimate the rocks’ age and origins.

The oldest were pebbles dating to the Early Cretaceous (around 130-110 million years old), followed by sandstone from the Late Cretaceous (around 95 million years old) and relatively young basalts from the Eocene (around 40 million years old).

The resulting maps of Zealandia transform it from a featureless mass into a place with many bands of distinctive geology running along its length from northwest to southeast. These fit together with the geology of West Antarctica like a jigsaw puzzle, confirming that this region and Zealandia once slotted together.

The next stage of the investigation looked at measurements of magnetic anomalies in the ocean floor around Zealandia. These variations in the strength of Earth’s magnetic field form an invisible record of how tectonic plates have moved around over time. They have revealed more about the continent’s ancient stretching, which continued for millions of years and even changed direction – leading to an ultra-thin continent that eventually sank.

BBC

So, what did it look like?

Behold, Zealandia.