Table of Contents

In C S Lewis’ The Silver Chair, a gnome from the land of Bism, at the bottom of the world, scoffs at surface-dwellers’ mines. “I have heard of those little scratches in the crust that you Topdwellers call mines.”

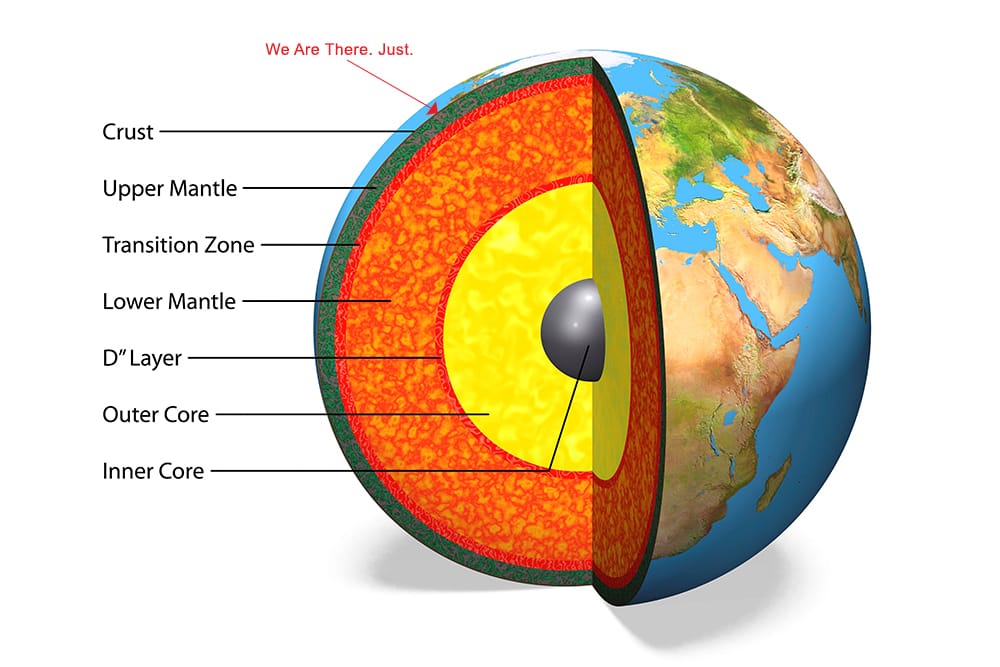

“Scratches in the crust” is putting it mildly. The deepest mine on Earth, the Mponeng gold mine, is four kilometres deep. That’s just a fifth of the average thickness of the Earth’s crust. Slightly more than a third of the depth of the deepest ocean trench.

As it happens, the bottom of the ocean is where the Earth’s crust is thinnest, thanks to plate tectonics. Which makes the mid-ocean the best place to drill to get to the mantle, the thickest layer of the Earth, which underlies the crust.

For more than 60 years, scientists have been trying to retrieve a rock from the upper mantle, but have failed to extract a large core sample. That, however, changed earlier this month when researchers onboard the JOIDES Resolution – the flagship vessel of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) that’s been scientifically scouring the ocean floor for decades – announced that they’d successfully retrieved a 1,000-kilometer-long* core of rock from the Earth’s upper mantle, consisting mainly of the rock peridotite.

“These are the types of rock we’ve been hoping to recover for a long time,” project co-lead Susan Lang, a biogeochemist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, told Science.

*This is a misprint. In fact, the sample is 1,000 metres. This is what happens when Americans can’t understand the metric system, I guess. Maybe they should have said that the sample was ‘80 school buses long’.

Still, such an astonishing sample has so far been unheard of. The previous record, set in 1993, was a mere 300 metres of serpentine peridotite. Peridotite is thought to be the dominant mineral in the upper mantle. Current samples are almost all ancient rocks that have been pushed up to the surface by the long processes of tectonics. Retrieving a sample from the mantle itself is another thing entirely.

Getting at mantle rock is an incredibly tricky process, seeing as the geologic layer is about 30 kilometers below the Earth’s surface on average. But the Atlantis Massif – just east of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge – bucks that average and brings the mantle much closer to the Earth’s surface through a process known as “ultra-slow seafloor spreading”, which occurs where two tectonic plates move away from each other.

“This enables the JOIDES Resolution the unique opportunity to drill and bring up this mantle rock which has not been altered by weathering on the surface, allowing scientists to provide us with new insights into the composition and structure of the mantle, as well as processes that take place within it,” the statement says.

Even so, some are not sure if this really is true mantle rock.

Although some scientists question if this 1,000-kilometer core is a true example of mantle rock (influences of seawater seen in the rock, for example, have caused some to be suspicious), the sample is clearly a never-before-seen glimpse into Earth’s geology. Scientists expect that this core sample could answer lingering questions about magma flows, earthquakes, mantle heat and a variety of other topics.

Popular Mechanics

To date, almost everything we’ve concluded about the deep interior of the Earth has been inferred by either rocks brought to the surface by weathering or vulcanism, or by measuring the changes in seismic waves sent through the Earth (kind of a rocky sonar). Making first-hand observations is another thing entirely.

Humans have been or sent probes orders of magnitude further into space than into our own Earth. We’ve just scratched a little deeper.