Table of Contents

I have written in The BFD recently about the decline of western Anglosphere nations through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. And that how, through a collapse in confidence, and also in morality, we have meekly accepted the suspension in civil liberties deemed by governments to be ‘necessary’ under COVID-19 – which has actually primed us for tyranny. Our acceptance of the Police State and massive government interference in our lives could have repercussions for the foreseeable future.

Like Judas we were easily bought, in our case not for thirty pieces of silver, but by the Wage Subsidy and the promise of a lie-down at home in front of Netflix. We succumbed to a politically-induced mass hysteria which does not align in any way with the severity of the situation in which we find ourselves.

Myles Harris tells an old Soviet joke in The Salisbury Review:

The difference between communism and capitalism is that under capitalism you are paid to work; under communism you are paid not to.

Just look at us now.

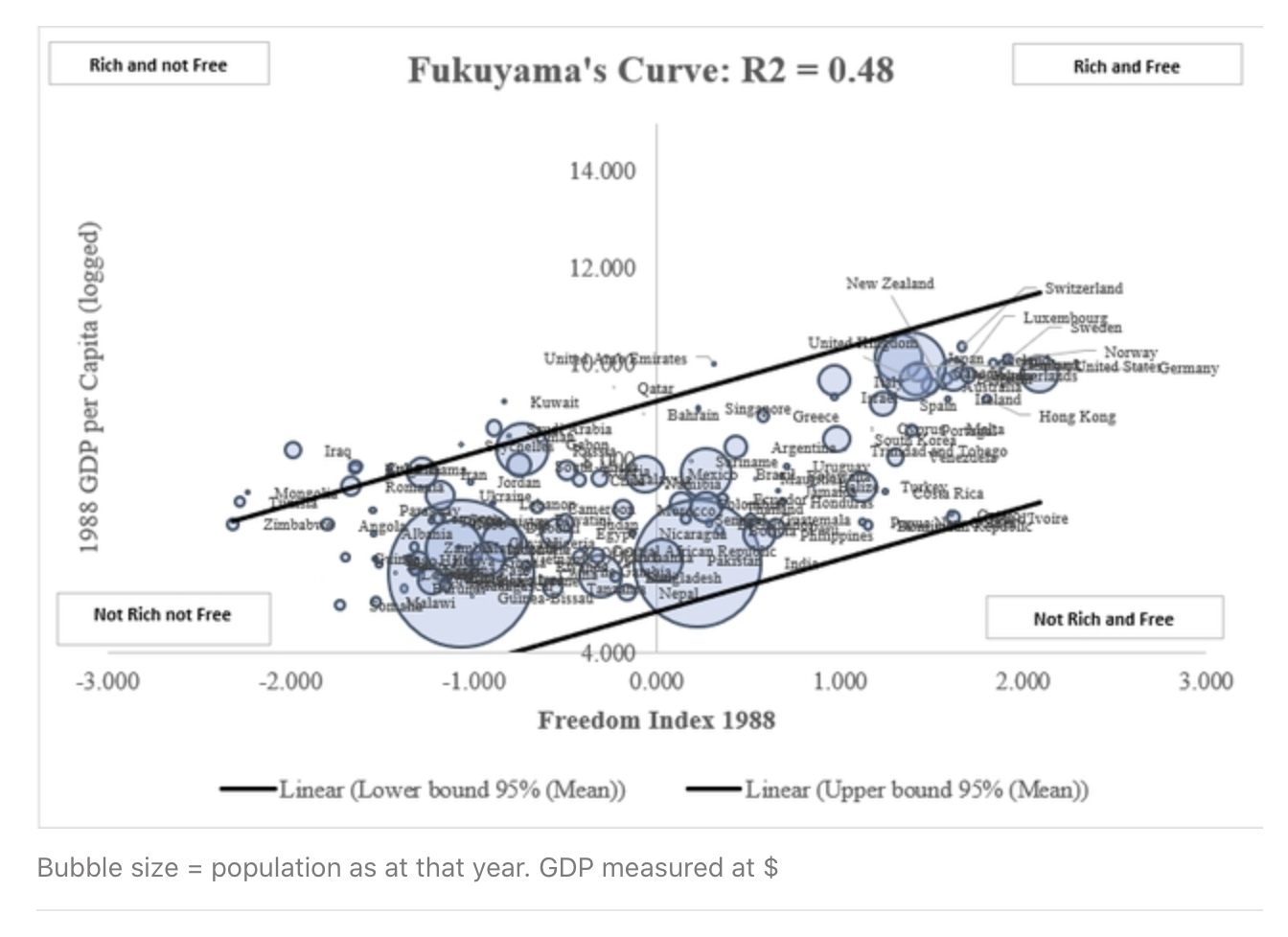

Writing from an economic perspective in The Spectator, James Kanagasooriam says that the West’s failure to reap benefit from its greater levels of personal and political freedom in recent years has broken both its confidence and the ‘Fukuyama Curve’. The Fukuyama Curve emerged from a graph of nations where freedom (via a ‘freedom index’) is measured on the x-axis against GDP per capita on the y-axis. At the time the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the graph produced a marked upwards curve with free western nations, having high levels of both freedom and GDP per capita, occupying the top right-hand end, and developing and Communist nations, having low levels of personal freedom and GDP per capita, finding themselves at the bottom left-hand end.

When the Soviet Union broke up, many of its smaller constituent parts were won over to the West by the ‘Fukuyama Curve’ – which showed a clear correlation between freedom and both personal and national wealth. Francis Fukuyama’s thesis that western liberal democracy would eventually become the model for governance worldwide appeared to be correct. The 1990s was an era of free-market oriented governments in Britain, Germany, the USA, Australasia and even France.

Kanagasooriam says that from the late twentieth century onwards things began to change, and there were three groups of countries which broke the trend of personal freedom equating to wealth. The first was the OPEC countries which, by virtue of geology, were able to amass petrochemical fortunes whilst doing little else. Second were Communist countries like The People’s Republic of China and its satellites. The Reds re-geared their economies towards inward knowledge transfer and then, focussing on exports, began to do much better than expected given their lack of freedom. The third were the ‘outlier’ countries such as Singapore which became rich while not ‘free’. It should be noted that, ‘back in the day’, Singapore had a GDP per capita the same as Sri Lanka’s.

In the first two decades of this century China proceeded to shatter the trend, disproving any correlation between wealth and freedom. Over the next 50 years China will give a ‘centrifugal pull’ to the economically growing and un-free world. Its pull, made even more attractive by politically-motivated financial aid and debt-servicing, will result in a widespread rejection of liberal democracy amongst those nations under Chinese influence. 15 percent of debt in the developing world is now believed to be owned by China.

Faced with low economic growth, low productivity, and wages which have not increased in real terms for years, western leaders have, according to Kangasooriam, focused only on the top layer of Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – self-expression and self-identity – without understanding the inherent socio-economic structures which lie beneath them. This is why we have spent the first two decades of the twenty-first century obsessing about LGBTQ issues, Treaty of Waitangi reparations, vegetarianism, minority rights, the place of Islam and ’social justice’, at the expense of almost everything else which supports them. We have not properly understood that, in the Hierarchy, it is economic security which comes first. It is the economy which provides the levels of safety and social security required to achieve these ‘less essential’ outcomes.

We in fact hived off most of our assets and outsourced nearly all of our economic production to China while we were kept busy fretting about personal pronouns.

The national discussion in New Zealand at the moment, monopolised as it is by the left, is currently about ‘realigning’ our priorities after COVID-19 and ‘reconnecting’ with nature and other things of apparent social importance – to the extent that we might not even really need ‘the economy’, we are told. This is Malthusian economics at its worst. To say that the confidence of Western nations, and the happiness of their populations, can flourish in a post-growth world is plainly wrong and needs to be strongly rebutted.

Most importantly, we need our freedoms back, and we need to use these freedoms to generate economic growth in order to make, in turn, the global case for greater freedoms.

What needs to happen to achieve this? Although it sounds obvious, the first thing we must do is to turf out the socialists at this year’s election. While potentially difficult (a ‘crisis’ suits the incumbent government) the solution does rest – at this point in time anyway – in the electorate’s hands.

Second, given the nature of MMP, we require more right-of-centre parties to be in parliament besides ACT. Parliament has no conservative voice at present, and this must change by bringing in the New Conservative party. A large number of New Zealanders are inherently conservative. It is frankly shocking that while recent parliaments have represented every shade of socialist and socio-environmentalist thought right through to proto-fascism, we have not had a properly Conservative party elected in decades. It is within the National party’s power – and very much in its interests – to make accommodations where necessary reflecting the MMP environment which we seem stuck with.

Thirdly, the National party needs to purge its ‘wet’ left wing if it is to properly become a party of the centre-right. It is not a party of the centre-right at present. The British Conservative party had its ‘road to Damascus’ moment during its existential struggle over Brexit. Previously blind to what was going on within the party and in government, the general public were made suddenly aware of how many Conservative MPs were not in fact conservative, nor even liberal. Defectors to the Liberal Democrats subsequently proved that ‘centrist’ party to in fact be both illiberal and undemocratic. If the Nats were to follow public opinion and ramp up some proper Trump-ist messaging, those who didn’t like it could de-select themselves or face de-selection.

One of the left’s most persistently successful messages, which has allowed the Labour party to effectively govern whilst not even in office, is that New Zealanders are, at heart, ‘progressive’. This is untrue. Rather, the electorate has been bullied into believing that it must seem to be progressive, lest it be called bigoted. We need to start electing strong and principled politicians who will stand up and say that our traditional values are the right ones.

Finally – and most importantly – we need to put in place a government which understands the primacy of the economy as the social driver. This needs to be a government which will seriously tackle the ‘welfare state’ and put our people back to work by not paying them to stay out of work. It needs to re-establish the family as the building block of society. It needs to seriously tackle crime, and drugs. It needs to stop our reliance on immigration to fuel an artificial ‘growth’ model.

We need to dis-establish the second tier universities, abolish their social-Marxist curriculums, and reinstate them as polytechnics to train tradesmen, engineers, technicians and craftsmen. We need to re-focus on manufacturing and exports, including value-add to primary industries. We need to domestically manufacture more products for our own use, such as building products.

We need to roll back legislation which interferes in people’s private lives, and which inhibits the things which people can say or think or do. This, we should insist, is an act more noble than protecting ‘hurt feelings’ or representing special interest groups.

We must prove that, as in times past, we can be both a free and an industrious nation. And that, through freedom, both industry and the economy may flourish.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.