Table of Contents

As I recently wrote, the only constant in the Earth’s history has been change. Not just the evolution of living creatures, or the never-ending ups and downs of climate change, but the very face of the planet itself.

It’s strange to think that, little more than a century or two ago, the idea that the global map was fixed and immutable was unchallenged wisdom. But then the advance of geology began to point out that what are now mountains were once at the bottom of the ocean. What are now frozen wastes were once steaming jungles.

But how did it get like that? For a long time, the Biblical flood was the obvious answer. But that didn’t hold up to scientific scrutiny. In Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, Jules Verne explains the leading scientific theory of the day: that what are now continents grew from atolls; what are now atolls will one day be the epicentres of new continents.

Less that half a century after Verne’s classic, though, a German scientist debunked that theory. Noting that the modern continents could suspiciously fit together like a jigsaw puzzle, Alfred Wegener proposed the theory of continental drift. With a mechanism to explain it — that the continental crusts are floating on a mantle of liquid rock — continental drift, or plate tectonics, is the accepted explanation of how the Earth came to look like it does.

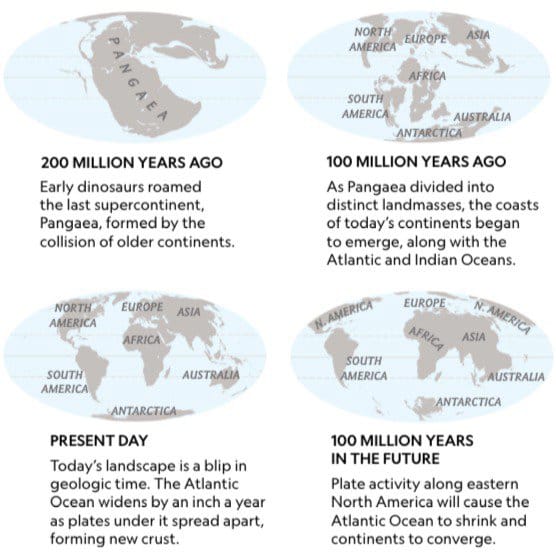

Using a combination of evidence, from “fossil” magnetic particles frozen in ancient rocks, to the distribution of fossil and modern plants and animals (for instance, the myrtle beech forests of New Zealand, Tasmania, India, South America and fossil remnants in Antarctica) to modern satellite measurements, scientists have “rewound” the geological clock.

The continents were once locked together in an ancient supercontinent dubbed Pangaea. Plate tectonics later broke Pangaea into Gondwana and Laurasia. Those, too, eventually broke apart into the shapes we recognise today.

But plate tectonics didn’t stop once the Earth assumed its current state. The Pacific Plate is still expanding, pushing continents apart. Australia, which over four billion years has bounced between the hemispheres, is once again drifting north.

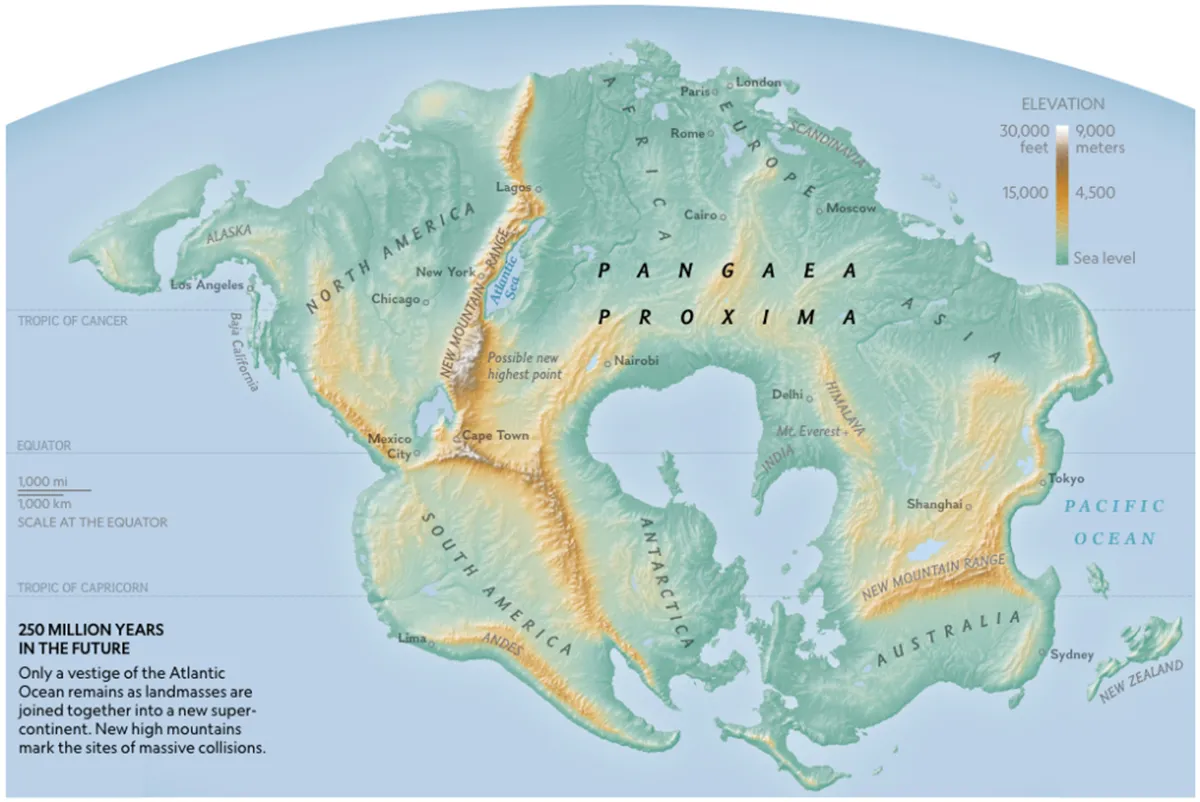

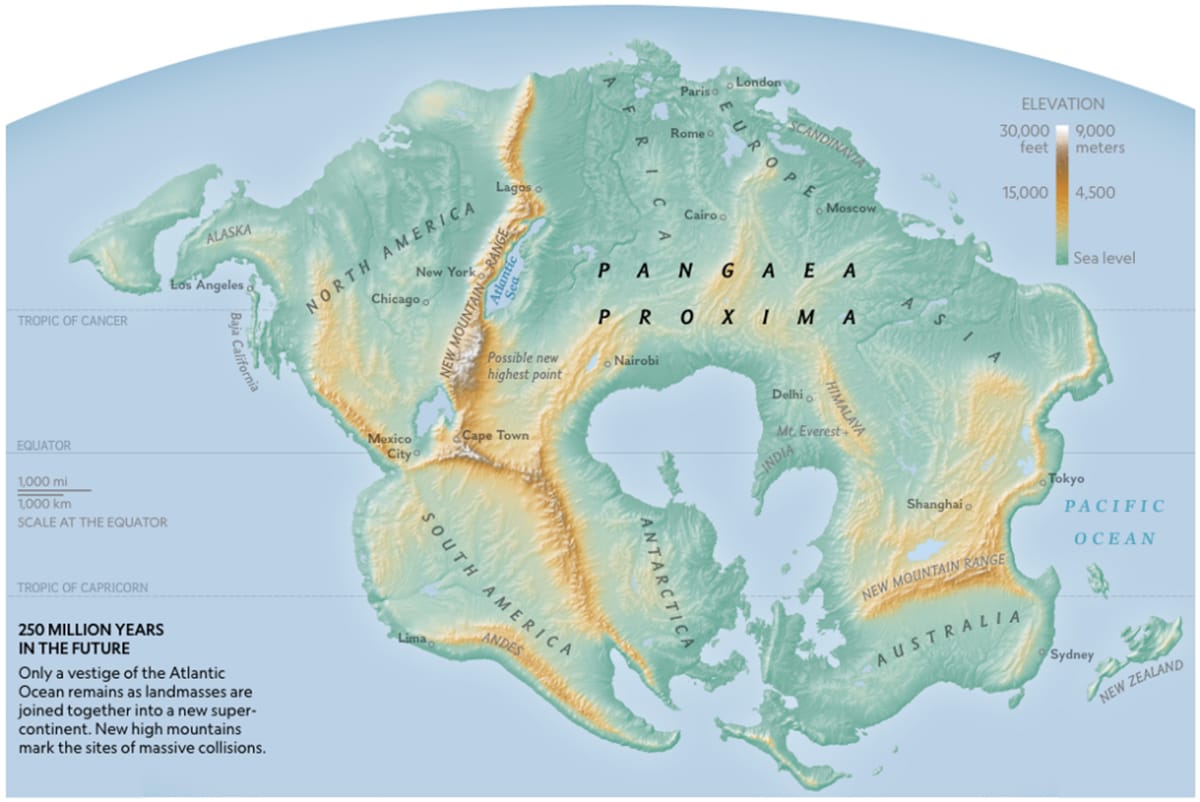

Putting together all the pieces, it’s therefore possible to make an educated guess and wind the clock forward and take a glimpse at the map of 250 million years hence.

Pangaea will return — as “Pangaea Proxima”.

The Americas along their current east coast will be fused to Africa in the north and Antarctica in the south. The Atlantic will be a rapidly diminishing lake — just as the once-mighty Tethys ocean remains only as the Caspian and Aral seas. The Indian ocean will still be a great stretch of sea, but rapidly meeting the same fate, as the pincers of Antarctica and Australia swing together in a reunion 250 million years in the making.

New mountain ranges will rise to humble the Himalayas. An as-yet-unnamed mountain range will arise where Florida and Georgia are folded up against South Africa and Namibia. Another towering range will fold up from what is now New Guinea, crushed up against south-east Asia. The Himalayas will still be a significant mountain range, though — it will take hundreds of millions years more to grind them down into low hills like the Central Australian hills which once towered as proudly as Everest.

If any humans remain, they will find that they can travel from Cape Town to Mexico city in a day. The Jetsons could take their flying car from Sydney to Shanghai without once crossing water.

Making Angela Merkel’s and George Soros’ jobs all the more easier, Europe will be fused to Africa. Fossilised Remainers will no doubt feel some justification that England will be merely the northernmost tip of a solid EurAfrican landmass.

One thing that won’t change though is that New Zealand will still be last, loneliest, loveliest, exquisite, apart.

Although north and south islands will be fused into an unrecognisable single body, still New Zealand will float in serene isolation in the South Pacific super-ocean, far from the cluster-connubiation of Pangaea Proxima.