Table of Contents

Peter MacDonald

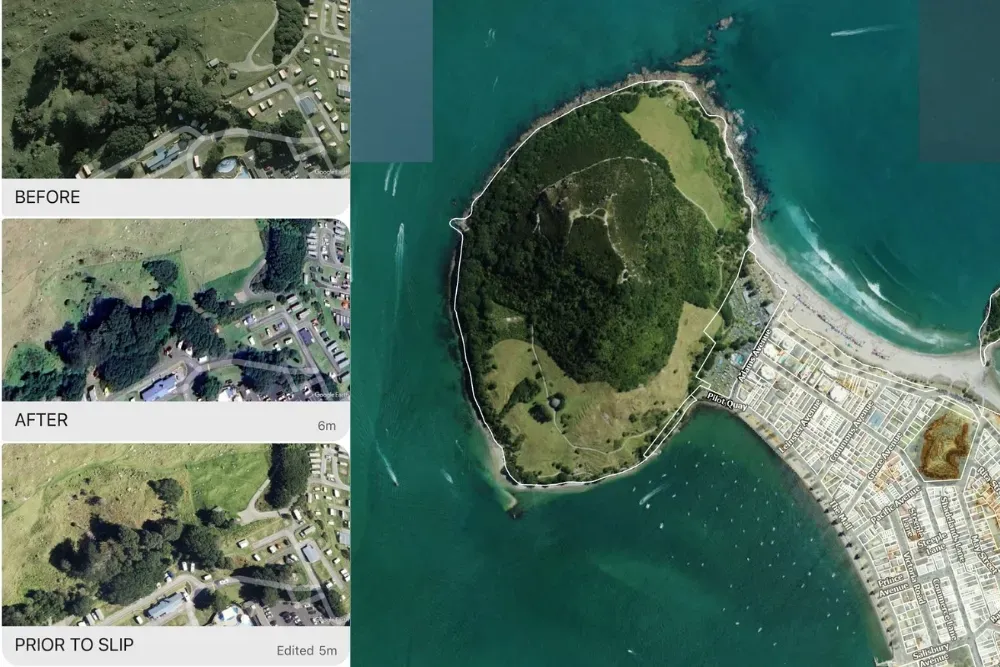

The Mount Maunganui landslide is being framed, almost from first principles, as an unavoidable act of nature unprecedented rain, climate change and bad luck. That framing is convenient – it is also incomplete. What happened at the Mount was not merely the product of weather: it was the end result of a series of authorised human decisions, taken years earlier, and then defended by ideology when the consequences arrived. To understand the disaster, we need to begin before the rain, not after it.

Step One, the Slope Was Altered By Policy, Not Accident

Mauao is not an unmanaged natural hillside. It is a formally governed historic reserve, subject to a detailed management regime adopted by Tauranga City Council. In 2018, the council approved the Mauao Historic Reserve Management Plan, which explicitly set out a programme for the progressive removal of “exotic” trees, including macrocarpa, pine, oak and other long-established species, in order to prioritise cultural, archaeological and ecological objectives.

That plan remains publicly available on the council’s website: Mauao Historic Reserve Management Plan (2018): https://www.tauranga.govt.nz/.../Parks-and.../Parks/Mauao

This was not a theoretical document. The policy was actively implemented.

In 2022 and 2023, Tauranga City Council closed sections of Mauao to carry out helicopter assisted exotic tree removal. Council notices at the time made clear that the work was being undertaken under the authority of the 2018 management plan and was intended to remove non-native trees from sensitive areas of the maunga.

Council confirmation of those works can be found here: Temporary Mauao closure for exotic tree removal (June–July 2023): https://www.tauranga.govt.nz/.../Temporary-Mauao-closure...

Mauao works complete, maunga reopened after tree removal (July 2023): https://www.tauranga.govt.nz/.../Mauao-works-complete...

These removals were justified publicly on cultural and restoration grounds. What was not publicly debated and appears not to have been integrated in a meaningful way was the engineering role those mature trees played in stabilising steep slopes, particularly in areas with a documented history of landslides.

Once those trees were removed, the slope’s margin for error was fundamentally reduced. From that point on, failure was inevitable. The only unknown variable was when.

Step Two, the Hazard Was Known and Compartmentalised Away

Mauao’s instability is not a new discovery. Landslides on the mountain have been mapped back decades. Tauranga City Council itself commissioned landslide risk studies in recent years. Yet hazard boundaries were drawn in ways that conspicuously excluded non-permanent accommodation areas, including the Beachside Holiday Park at the base of the slope. Risk, in other words, did not disappear – it was administratively bounded.

This is how bureaucratic systems neutralise danger: one department signs off vegetation removal, another maps hazards, another manages parks, another oversees emergency response. Each operates ‘within scope’. No one owns the whole risk. When the slope finally fails, responsibility dissolves into process.

Step Three, the Rain Came, as It Always Eventually Would

When the record rainfall arrived, it did not create a new risk. It merely activated an existing one. Rainfall does not cause landslides in isolation: landslides occur when water overwhelms slopes that have already been structurally weakened.

Calling the event “unprecedented” obscures the truth that the physical conditions for failure had already been authorised.

Step Four, Rescue Was Ideologically Deferred

When the slip came down, a final layer of ideology asserted itself, this time in the response. Eyewitnesses report that civilians attempting immediate rescue were ordered to stop. Mark Tangney, a Whakatāne man who works in the area, rushed to help campers trapped in a toilet block.

“I was one of the first there,” Tangney told the Bay of Plenty Times. “There were six or eight other guys there on the roof of the toilet block with tools just trying to take the roof off because we could hear people screaming, ‘Help us, help us, get us out of here.’”

Tangney said they worked frantically for about 30 minutes. “After about 15 minutes, the people that were trapped… we couldn’t hear them anymore.”

Then, police arrived and ordered the civilians to stand down. The rescue was called off because the site was deemed ‘too dangerous’. Tangney described the scene: the mud had pushed about six caravans and twisted the toilet block roughly 20 metres from its original position.

This is the moment where ideology becomes lethal. People were alive. They were heard. Civilians were acting. And then they were ordered to stand down. That is the operationalisation of risk-averse bureaucracy, an abstract doctrine determining life or death, while survivors are left on their own.

This pattern is now embedded across New Zealand’s emergency services: no action until safety can be guaranteed. Waiting until a scene is ‘safe’ guarantees that anyone who cannot self-rescue will die. The same pattern was visible at Pike River, White Island and now again at Mount Maunganui.

Step Five, Climate Change as the Shield

Only after all of this do we arrive at the climate narrative. Climate change did not order the removal of stabilising trees. Climate change did not draw hazard maps that stopped at the edge of tourist accommodation. Climate change did not instruct rescuers to stand down while civilians were digging.

But, in this case, it is also being used as cover, a way to dissolve responsibility into atmosphere and abstraction, rather than naming the specific decisions, approvals and ideologies that placed people directly in harm’s way.

This Was Not Fate

The Mount Maunganui disaster was not simply ‘one of those things’ or an act of God. It was the foreseeable outcome of authorised slope modification, compartmentalised risk management and an emergency doctrine that has redefined rescue as optional.

The dead were not unlucky. They were failed long before the rain fell. If we continue to describe events like this as apolitical acts of nature, we guarantee their repetition. The politics are already there in the plans we approve, the trees we remove, the risks we redraw and the rescues we decide are too dangerous to attempt.