Table of Contents

The National Government has announced just two targets for the Ministry of Social Development. They are:

– to reduce the number of people receiving Jobseeker Support by 50,000 to 140,000 by June 2029, and

– (alongside HUD) to reduce the number of households in emergency housing by 75 percent, by June 2029 – this is fewer than 800 households in emergency housing.

The first of these targets is incredibly timid and disappointing.

A reduction of Jobseekers down to 140,000 by June 2029 is still more than there were in June 2019 (136,233).

To put the target in context, in the year to January 2024, NZ added 133,800 net migrants. If just a third of these found work (assuming the balance are students or dependents of the primary migrant) that represents 44,600 extra jobs. In one year. How hard can it be to find a job if you really want and need one?

Interviewed by Mike Hosking earlier this week, former WINZ boss Christine Rankin said that the target reduction “can be done in way under the time frame they’ve put on it”. She should know.

To achieve the target the government says there will be, “a stronger focus on helping 18–24-year-olds on Jobseeker Support into jobs.” Announcing where a stronger focus will be risks the pressure going off other beneficiaries in the minds of both case managers and clients. Numbers on the Sole Parent Support (ex DPB) have been increasing steadily. Given sole-parent households contribute substantially to inter-generational dependency, they merit no less focus than Jobseekers.

Reaching the reduced goal will happen by, “making it easier for people with work obligations to understand and meet expectations.” How hard can it be to understand an obligation to find work? Isn’t this simply an acknowledgement that over the past six years, obligations became fuzzy and weak? So why is a reversal of Labour’s soft approach couched in such … soft language?

And what about those who don’t have work obligations?

In 2012, during Paula Bennett’s time as minister, obligations were placed on single parents to return to work earlier if they had an additional child while receiving a benefit. Carmel Sepuloni removed that requirement effectively allowing the birth of more babies to be used to avoid working.

As it is sole parents have no work obligations until their youngest turns three (and then it is only to seek part-time work.) Three years is inconsistent with the time most working mothers take out of the workforce.

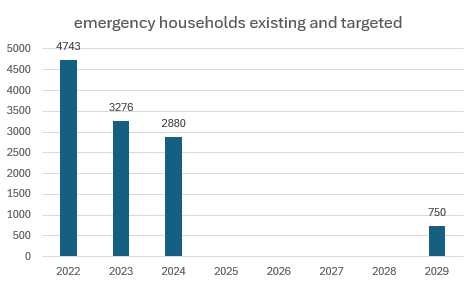

The government’s second target appears no less lacking in ambition. Emergency housing numbers have already been tracking down. Depicting them next to the 2029 target looks like this:

A continuation of whatever policy operated between 2022 and 2024, which saw a 39 per cent reduction in emergency housing, would see the target of 750 met much sooner than 2029.

Come on National.

You were elected to be bold. Kids in emergency housing don’t have the luxury of time.

Neither does the rest of country. Our deep-seated, long-standing dependency problem, which is an economic handbrake and social disaster, needs urgent reform – not timid targets.