Table of Contents

John Maunder

For further information on a range of weather and climate matters see my recent book Fifteen shades of climate… the fall of the weather dice and the butterfly effect. Available from Amazon.

The following is an update on the subject from pages 171 to 173 and 180 to 182 of the book.

The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) is a standardized index based on the observed sea level pressure differences between Tahiti and Darwin, Australia. The SOI is a leading measure of the large-scale fluctuations in air pressure occurring between the western and eastern tropical Pacific (i.e., the state of the Southern Oscillation) during El Niño and La Niña episodes. In general, smoothed time series of the SOI correspond very well with changes in ocean temperatures across the eastern tropical Pacific.

The negative phase of the SOI represents below-normal air pressure at Tahiti and above-normal air pressure at Darwin.

The positive phase of the SOI represents above-normal air pressure at Tahiti and below-normal air pressure at Darwin.

Prolonged periods of negative SOI values coincide with abnormally warm ocean waters across the eastern tropical Pacific typical of El Niño episodes.

In contrast, prolonged periods of positive SOI values coincide with abnormally cold ocean waters across the eastern tropical Pacific typical of La Niña episodes.

Sustained negative values of the SOI below ?8 often indicate El Niño episodes. These negative values are usually accompanied by sustained warming of the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, a decrease in the strength of the Pacific Trade Winds.

Sustained positive values of the SOI above +8 are typical of a La Niña episode. They are associated with stronger Pacific trade winds and warmer sea temperatures to the north of Australia. Waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean become cooler during this time.

The graph below ( from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, BOM) shows monthly values of the SOI from January 2020 to May 2022.

The 2021–22 La Niña continues in the tropical Pacific, with little change in strength in the past few weeks.

Several indicators of La Niña, including tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures, cloudiness near the Date Line, and the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), have maintained or slightly increased their strength over the past fortnight. However, beneath the surface of the tropical Pacific, waters have warmed closer to neutral El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) levels.

Most climate models surveyed by the Bureau indicate a return to neutral ENSO by the early southern hemisphere winter. Only one of seven models continues La Niña conditions through the southern winter. La Niña conditions increase the chances of above-average rainfall for much of eastern Australia, while neutral ENSO has little influence on rainfall patterns.

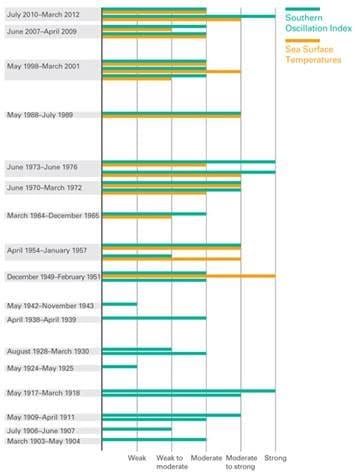

La Niña events over time

As La Niña events recur on a two to seven-year cycle, there have been many over the last century, varying in strength and impacts. The SOI and sea surface temperatures can be used to compare the intensity of La Niña events. (See graph below)

Atmospheric and oceanic intensity of La Niña events since 1900. Intensity is ranked by SOI values for atmosphere, while oceanic intensity is ranked by sea surface temperature indicators (only available reliably since mid-century). Some multi-year events have two or three La Niña peaks.

El Nino and La Nina weather affects over New Zealand (Source Niwa)

During El Niño, New Zealand tends to experience stronger or more frequent winds from the west in summer, typically leading to drought in east coast areas and more rain in the west.

In winter, the winds tend to be more from the south, bringing colder conditions to both the land and the surrounding ocean.

In spring and autumn southwesterly winds are more common.

La Niña events have different impacts on New Zealand’s climate. More northeasterly winds are characteristic, which tend to bring moist, rainy conditions to the northeast of the North Island, and reduced rainfall to the south and south-west of the South Island.

Therefore, some areas, such as central Otago and South Canterbury, can experience drought in both El Niño and La Niña.

Warmer than normal temperatures typically occur over much of the country during La Niña, although there are regional and seasonal exceptions.

Although ENSO events have an important influence on New Zealand’s climate, it accounts for less than 25 per cent of the year to year variance in seasonal rainfall and temperature at most New Zealand measurement sites.

BUY Your Own Copy of Dr John Maunders book Fifteen Shades of Climate Today.