Table of Contents

Michael Cook

Michael Cook is the editor of MercatorNet. He lives in Sydney, Australia.

The Economist, an oracle for politicians, journalists and economists everywhere, has turned bearish on the future of humanity. The theme of its latest cover story is that world is running out of people.

Exhibit A in its sombre look at the future of the world economy is a seven-minute mockumentary produced by the Italian baby food manufacturer Plasmon. It’s called “Adamo 2050 | A true story from the future”. “Adam is a special child,” says the narrator. “He’s the last child born in Italy.” The camera pans across empty maternity wards and empty classrooms.

The film exaggerates – there will still be bambini in Italy’s playgrounds in 2050 – but the problem is real. One of the country’s leading demographers, Alessandro Rosina, says in the film that Italy, with a birth rate of 1.24 (2.1 is necessary to maintain the existing level of population), is the first country in the world where there are more grandparents than children.

The Economist’s leader (editorial) declares: “in much of the world the patter of tiny feet is being drowned out by the clatter of walking sticks. The prime examples of ageing countries are no longer just Japan and Italy, but also include Brazil, Mexico and Thailand.”

The focus of the Economist’s concerns is, of course, the economy. Prosperity depends on productivity. If there are fewer people, those remaining will have to be more productive and creative. But old folks tend not to be creative.

Older countries – and, it turns out, their young people – are less enterprising and less comfortable taking risks. Elderly electorates ossify politics, too. Because the old benefit less than the young when economies grow, they have proved less keen on pro-growth policies, especially housebuilding. Creative destruction is likely to be rarer in ageing societies, suppressing productivity growth in ways that compound into an enormous missed opportunity.

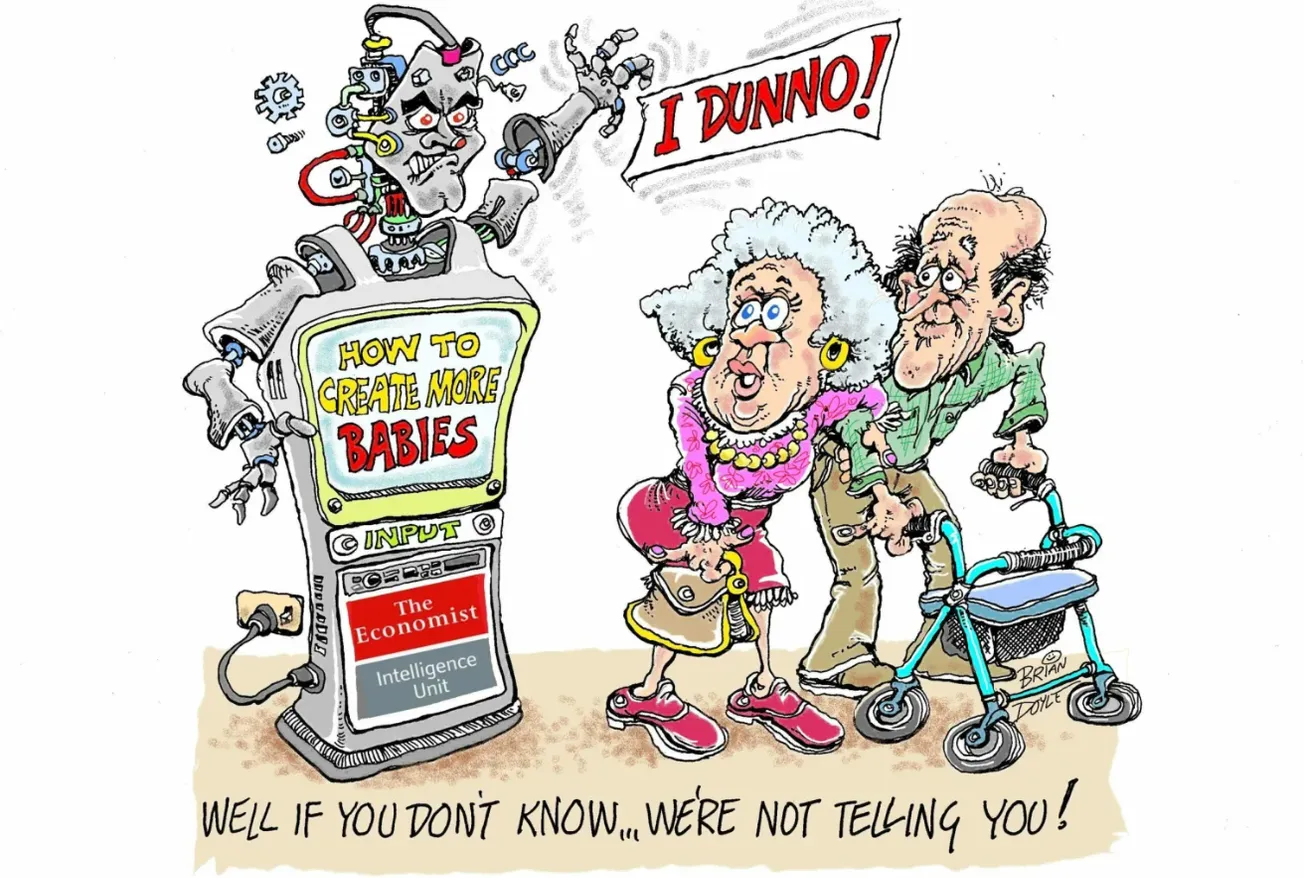

So what is to be done? Dunno, says the Economist. Like nearly everyone else, its brainiacs are stumped. One by one, the leader ticks off solutions which are being proposed around the world:

Immigration? Nope. “The global nature of the fertility slump means that, by the middle of the century, the world is likely to face a dearth of young, educated workers unless something changes.”

Pro-family subsidies? Nope. “Singapore offers lavish grants, tax rebates and child-care subsidies – but has a fertility rate of 1.0.”

More and better education? Nope. There are short terms gains to be made by educating people in Africa, China and India. But “encouraging development is hard – and the sooner places get rich, the sooner they get old”.

ChatGPT? Aha! There’s an idea! The Economist wheels the latest fad, AI, out as its most promising nominee for a productivity revolution.

“An über-productive AI-infused economy might find it easy to support a greater number of retired people. Eventually AI may be able to generate ideas by itself, reducing the need for human intelligence. Combined with robotics, AI may also make caring for the elderly less labour-intensive. Such innovations will certainly be in high demand.”

Even to the brainiacs at the Economist, this must sound deluded. The leader limps along to its facile conclusion: “Fewer babies means less human genius. But that might be a problem human genius can fix.”

No, AI is not going to save Italy and the rest of the human race from extinction. Human genius will fail to motivate women to have babies. The only solution is a spiritual revival. Men and women need to rediscover the joy of bringing new life into the world and the confidence that they can work through the challenges of raising children. Short of that, nothing is going to work.