Table of Contents

“But that sunset! I’ve never seen anything like it in my wildest dreams … the two suns! It was like mountains of fire boiling into space.”

“I’ve seen it,” said Marvin. “It’s rubbish.”

– Douglas Adams, “The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy”

It’s one of the most iconic shots in modern cinema: the twin suns of Tatooine setting in Star Wars. Set to the stirring music of John Williams, it reminds us that this really is another world, totally unlike our own.

Except that, barring the vicissitudes of cosmic evolution, it could have been.

Recent cosmology suggests that most stars in fact form, at least initially, as binary (two-star) systems. Our own may well have been no different.

A new paper presents a model supporting the theory that the Sun may have started out as one member of a temporary binary system. There’s a certain elegance to the idea – if it’s true, this origin story could resolve some vexing solar-system puzzles, among them the genesis of the Oort Cloud, and the presence of massive captured objects like a Planet Nine.

First, a basic primer on what we now believe about the Solar System. Most of us grew up with the picture of the Sun surrounded by the nine (now eight) planets rotating around it on a more or less flat plane, like a series of concentric rings. It turns out, though, that it’s a bit more complicated than that.

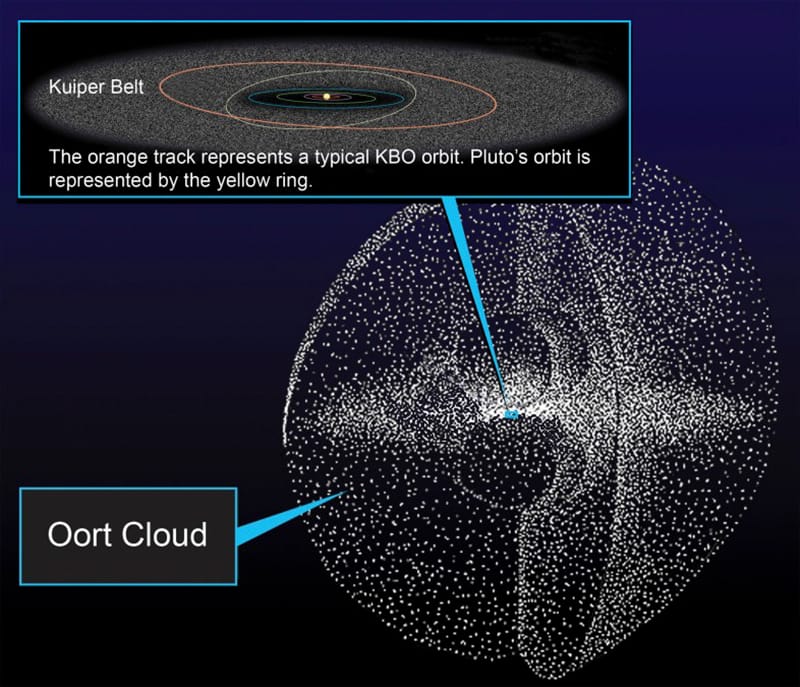

There’s the Kuiper Belt, another flat disc, kind of like an icy asteroid belt, surrounding the Sun from roughly the orbit of Neptune to way out past Pluto. This belt of ice-balls is believed to be the source of short-term comets (ones that take less than centuries to orbit the Sun).

But, out past that, it’s believed, is the Oort cloud. Unlike the Kuiper Belt, it’s not a belt at all but a spherical shell composed of over a trillion icy objects more than a mile wide and generally assumed to be comprised of debris from the formation of the solar system and neighboring systems – stuff from other systems that we somehow captured. The Oort cloud is surmised to be the origin of longer-term comets, which take 200 years or more to orbit the Sun.

And it’s big – really big: between 2,000 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun to about 100,000 AU (an AU is the distance from the Sun to the Earth). By tracing back the orbits of long-term comets, astronomers have been able to build up a picture of this icy ‘cloud’.

No object in the Oort cloud has been directly observed, though Voyager 1 and 2, New Horizons, and Pioneer 10 and 11 are all en route. (The cloud is so far away that all five of the craft will be dead by the time they get there.) To derive a clearer view of the Oort cloud absent actually imagery, scientists utilize computer models based on planetary orbits, solar-system formation simulations, and comet trajectories.

But the Oort cloud also throws a cosmic spanner in previously held ideas of the Sun as a cosmic only child.

However, says paper co-author Amir Siraj of Harvard, “previous models have had difficulty producing the expected ratio between scattered disk objects and outer Oort cloud objects.” As an answer to that, he says, “the binary capture model offers significant improvement and refinement, which is seemingly obvious in retrospect: most sun-like stars are born with binary companions.”

“Binary systems are far more efficient at capturing objects than are single stars,” co-author Ari Loeb, also of Harvard, explains. “If the Oort cloud formed as [indirectly] observed, it would imply that the sun did in fact have a companion of similar mass that was lost before the sun left its birth cluster” […]

The gravitational pull resulting from a binary companion to the Sun may also help explain another intriguing phenomenon: the warping of orbital paths either by something big beyond Pluto – a Planet 9, perhaps – or smaller trans-Neptunian objects closer in, at the outer edges of the Kuiper Belt.

So, where did Sun 2.0 go?

Says Loeb, “Passing stars in the birth cluster would have removed the companion from the sun through their gravitational influence. He adds that, “Before the loss of the binary, however, the solar system already would have captured its outer envelope of objects, namely the Oort cloud and the Planet Nine population.”

So, where’d it go? Siraj answers, “The sun’s long-lost companion could now be anywhere in the Milky Way.”

As for the Oort cloud and a putative ‘Planet 9’, we might be able to directly observe them, soon.

The authors are looking forward to the upcoming Vera C Rubin Observatory (VRO) , a Large Synoptic Survey Telescope expected to capture its first light from the cosmos in 2021. It’s expected that the VRO will definitively confirm or dismiss the existence of Planet 9. Siraj says, “If the VRO verifies the existence of Planet Nine, and a captured origin, and also finds a population of similarly captured dwarf planets, then the binary model will be favored over the lone stellar history that has been long-assumed.”

The long-lost solar sibling even has a name: Nemesis.

The reason for the ominous moniker is because it has been hypothesised that, on its way out the door to the depths of the galaxy, the wandering star may have kicked an asteroid into a fateful path with the Earth. A path which, 65 million years ago, collided and wiped out the dinosaurs.