Table of Contents

Peter MacDonald

The latest, Bloody Sunday trial, in the UK, is just the most recent chapter in the drawn out saga of Bloody Sunday. More than 50 years after the shootings, a former parachute regiment soldier known in court only as Soldier F, has been found not guilty of murder and attempted murder relating to the deaths of James Wray and William McKinney, along with five counts of attempted murder. The verdict was reported by the BBC on 24 October 2025.

Judge Patrick Lynch told the court that members of the Parachute Regiment who entered Glenfada Park North had “totally lost all sense of military discipline”, shooting unarmed civilians fleeing across the streets of Derry. Despite the judge’s criticism, the legal threshold for conviction was not met. Soldier F’s acquittal underscores the enduring difficulty of delivering justice in a case stretching back over half a century, following decades of investigations, public inquiries and numerous trials of former soldiers implicated in the Bogside shootings. Families and the wider community continue to live with the pain and unanswered questions that began on 30 January 1972.

For decades, this latest inquiry, and every other previous inquiry and investigation, has delivered answers carefully calibrated to the ‘establishment approved chaos’, version, leaving unanswered questions in order to protect the institution from scrutiny.

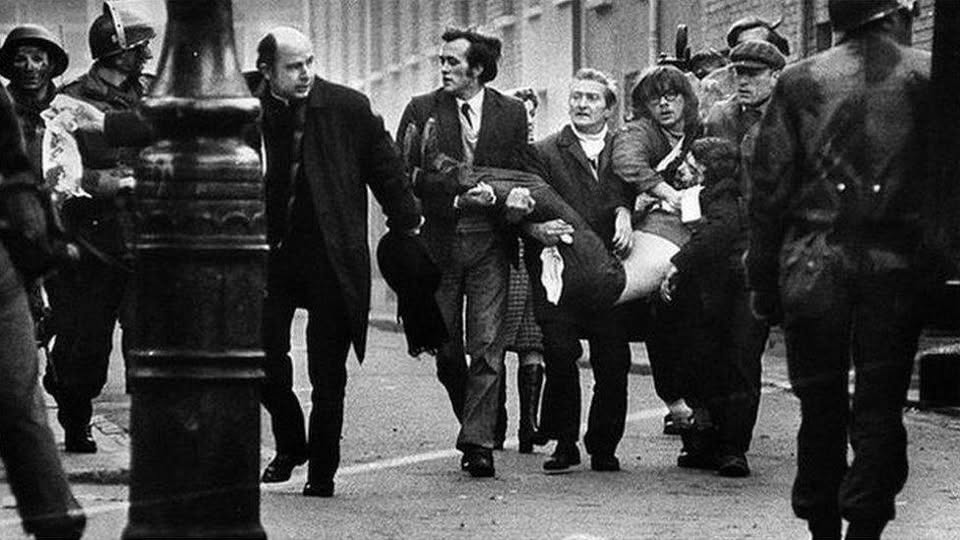

I have followed the events of Bloody Sunday since that day, when 14 unarmed civilians were shot in Derry’s Bogside during a peaceful civil rights march. Over the years, through documentaries, newspaper reports and interviews, the horror of that day has remained clear.

Among the soldiers present was Costas Georgiou, later known as Colonel Callan. Georgiou served as a private in the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, during his time in Northern Ireland: the title “Colonel Callan” was not a British Army rank but a nom de guerre he adopted while operating as a mercenary in Angola, where he led operations with ruthless and unrestrained violence. In Angola, fellow mercenaries described him as unhinged and a psychopath.

Fellow soldiers publicly stated in interviews in the 1970s, including archived television footage, that Georgiou was the main perpetrator in Derry, firing an entire SLR magazine into a crowd of civilians. At distances often less than 50 metres, those rounds could pass through multiple bodies and, fired from the hip or shoulder, a single burst could have killed most of the victims. Speaking from my own experience as an ex-soldier, I know the destructive power of a high-powered rifle at close range. On army shooting ranges, I’ve engaged close range targets and seen how rapidly a magazine emptied at 50 metres or less can devastate a target area in seconds.

Over the years, there have been claims that IRA men, hidden in buildings, fired first at the British paratroopers. These claims have been completely debunked by multiple inquiries, including the Saville Inquiry, which confirmed that all casualties were inflicted on fleeing civilians. The shootings were deliberate and uncontrolled, aimed at people running for their lives. The soldiers claims that they had come under fire from hidden IRA members have now been thoroughly discredited.

The march had been blocked by army barricades on William Street, funnelling civilians south toward Rossville Street and the Rossville Flats. Soldiers took positions along Rossville Street and the flats’ forecourt, while civilians fled across Glenfada Park North and toward Free Derry Corner, often less than 30 to 80 metres from the firing positions. Nearly all victims were hit while fleeing or aiding the wounded, consistent with elevated northern firing positions. One soldier with a full magazine at that distance could cause the majority of casualties in seconds. Callan fits that pattern.

His career in the British Army was brief but disturbing. Born in Cyprus in 1951 and raised in London, he joined the 1st Battalion, parachute regiment. He was a crack marksman, known as the best shot in his regiment, but also a dangerous man with a volatile temperament. While serving in Belfast during the Troubles, he gained a reputation as a ‘hardman’, provoking confrontations with Catholic youths and taking pleasure in violence. Within a month after Bloody Sunday, in February 1972, he and three fellow paratroopers committed an armed robbery at a post office, stealing £93. Georgiou and one of the others were court martialed, cashiered from the army and sentenced to five years in prison. They were released in 1975 and immediately went to Angola as mercenaries.

In Angola, Georgiou’s [Callan’s], violent tendencies escalated dramatically. Fellow mercenaries described him as psychopathic, unhinged and sadistic. He personally executed deserters and mutineers, shot allies who questioned him and killed African recruits for minor mistakes. One contingent of new mercenaries, mostly inexperienced working class men, believed they had come to Angola as non-combatants and decided to leave. After Callan insisted they were there as combatants, he rounded them up at gunpoint and had them summarily executed, creating terror among his men. The situation became so extreme that Angolan President Agostinho Neto approached British mercenary Colonel Peter McAleese to intervene and bring an end to Callan’s rampage. Callan briefly evaded capture by fleeing into the jungle.

Georgiou evaded capture for months, continuing to fight until he was eventually caught by MPLA forces and tried by the Angolan government in 1976 for war crimes. Alongside 12 other Western mercenaries, he was charged with illegal combat, war crimes and waging an unlawful war of aggression. The charges were based on attempts to extinguish Angola’s independence, oppress its people and pillage its resources for foreign interests.

This extreme violence demonstrates the kind of lethality he brought to the Bogside in Derry. Soldiers who watched him unload his SLR that day were witnessing the same unrestrained aggression that later manifested in Angola: precise, fast and deadly. His paratrooper training deliberately designed to instil aggression, desensitise recruits to violence and push men beyond normal moral restraints had fused with a violent mind – producing a soldier capable of killing without conscience.

Yet in Northern Ireland, the UKGovernment and the British Army swept this under the carpet, aware that acknowledging Callan’s actions would expose the extreme aggression deliberately induced in their training methods a method that could, and did, push soldiers with unstable minds like his off the rails. For 50 years, reporting of this tragedy has been used as a cultural distraction, a source of revenue for tabloid media, and a profit engine for lawyers involved in the endless trials and inquiries.

Had Callan been publicly identified in 1972 by his fellow soldiers and the British media, the families of the victims could have had closure decades ago. Instead, institutional self-preservation, media manipulation and legal spectacle left the truth obscured.

Conclusion

Bloody Sunday is a cautionary tale of unrestrained violence, reckless military conditioning and deliberate obfuscation. Families were left in limbo, history partially hidden and a soldier who knew no restraint – unhinged, sadistic, and lethal – became a symbol of institutional failure. For decades, the answers delivered by inquiries have perpetuated what can only be called ‘establishment approved chaos’, leaving truth and accountability subordinated to protecting the institution. That is the shadow that still hangs over Derry and over the memory of those who were killed and wounded.

Sources:

Saville Inquiry Report (2010), Volumes I & II – Report of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, UK Government.

BBC News, “Bloody Sunday: Key events in Derry in 1972,” 24 October 2025.

Chris Dempster and Dave Tomkins, Fire Power, Corgi, 1978 – for accounts of Georgiou in Northern Ireland.

Peter McAleese, No Mean Soldier, 2006 – for firsthand accounts of mercenary operations in Angola and Georgiou/Callan’s actions.

YouTube, “McAleese on mercenaries’ killings,” recorded 18 February 1976, published 23 July 2015 – interview detailing Callan’s rampage and McAleese’s intervention.