Table of Contents

Tiger

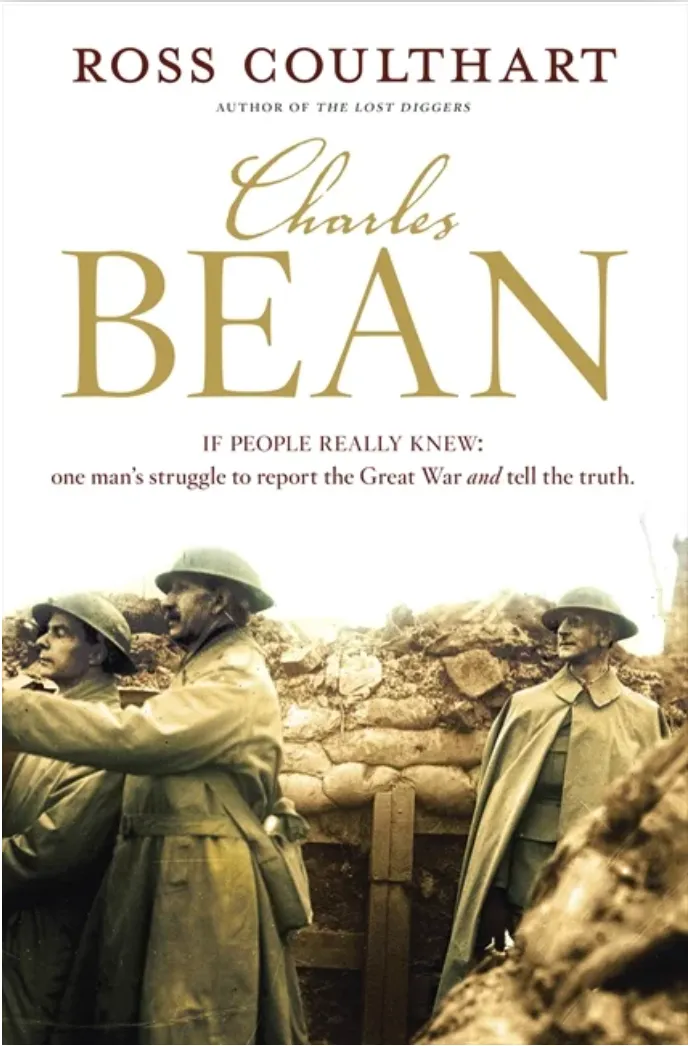

Charles Bean – If people really knew – one man’s struggle to report the Great War and tell the truth by Ross Coulthart, Harper Collins.

Censorship is nothing new. Censorship by whom we might call the “good guys” is nothing new either. By censoring the message, the truth can be bent to favour the narrative of the day. It was no different in the Great War (1914-1918).

This book offers insight into two themes. One was the creation of the ANZAC identity, the other was the story of how difficult it was to tell the truth about the Great War as it unfolded. These themes are set amongst some of the grittiest reporting from what would be termed a “war correspondent”, on account of Charles Bean’s ability to get to the front lines to find the truth. The dangers Bean faced were phenomenal but no different from those of the front-line soldiers. Arguably Bean’s weapon was potentially more powerful than any of the ordnance found on the Western Front: his pen. But the British army was not that keen to have the truth told.

Charles Bean was an educated man from Australia. Initially trained as a lawyer, he gravitated to writing for newspapers. News back in the early 1900s was a growth industry and newspapers were the medium. As the war started in Europe, the fledgeling Australian government wanted their own reporters on the scene, attached to their military. Of course, the colonial forces were not good enough to be run by colonial generals, so from the outset, they were commanded by British generals.

Charles Bean had a unique style of reporting, actually living amongst the troops and surveying the front lines in person. Post-battles he would walk amongst the dead and dying, piecing together the events. He kept copious diaries, from which he wrote dispatches, only to have them watered down for public consumption. The differences were stark.

In one of many incidents, Bean was brought before the general of the 6th Battalion of the British Manchester Regiment and dressed down for writing of the catastrophic failures in leadership, supply and the impossibility of doing what was commanded in battle. General Haig, by the way, was sitting comfortably in a Louis XVI gilt chair 100 miles behind the line in Amiens at the start of the battle of Passchendaele. Censors were “terrified of making a mistake, so their instinct was to ban almost every detail”.

The real gift Charles Bean gave us is in the description of the Australian and New Zealand soldiers, from their shambolic discipline in Cairo, their initiative and heroism at Gallipoli, to their sheer doggedness on the Western front. But the truth was only allowed out when Charles Bean was able to write freely from his vast library of diaries and first-hand accounts after the war. From his writings was born the legend of the “ANZAC spirit”.

This book gives a weighty account of Charles Bean’s upbringing in rural New South Wales, his move to Britain, his studies and his move back to Australia. This upbringing gave Charles insight into the differences between the young men from both countries. We owe much to Charles Bean for informing our predecessors of the truth of how the ANZACs acquitted themselves in a war, largely run by out-of-touch and incompetent leaders. But we also owe Charles Bean and the author of this book for highlighting the struggle to tell the truth from what we would be led to believe were the “good guys”.