Table of Contents

As you should be well aware by now, I’m pretty chary of “social science” research. Especially when they just conveniently agree with our preconceptions. But when studies upend commonly-held, “Well, everyone knows that” stereotypes, then they’re already potentially more interesting.

One recent such study looked at how well cats and cat-owners understand one another.

This is already standing out from the field, because studies of cat behaviour are relatively rare — for the simple reason that cats are, as the stereotype goes, so cussedly unco-operative. Dogs, on the other hand, seem to exist to please.

Compared to the owner-dog dynamic, owner-cat relationships are often characterised by different owner qualities, attitudes towards, and perceptions of their pets, in addition to different animal-owner and owner-animal attachments.

Or, as urban lore would have it, “Crazy Cat Ladies” are weird and neurotic, and their cats are only using them for food.

However, across these studies, details of the specific cat-handling styles exhibited by humans during HCI, and their associations with human-individual differences and cat comfort were not included.

Nature

In other words, do “cat people” really understand their feline friends as well as they think they do? And does Mr Tiddlekins really like being carried around and dressed up in cute little outfits for Facebook photos?

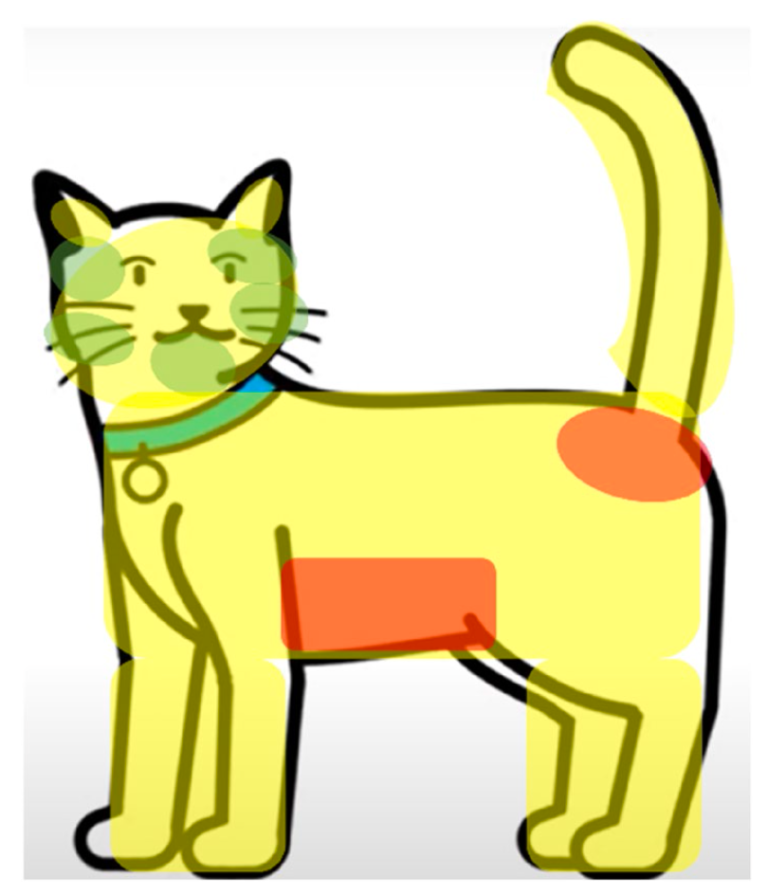

In research published last year, Dr. Lauren Finka, a feline welfare and behavior scientist at Cats Protection and a Visiting Fellow at Nottingham Trent University, characterized how to interact with our feline friends in ways that they actually enjoy. Allowing cats to decide when to be pet, refraining from picking them up, generally touching them less, and — if they show interest in being touched – focusing on the base of their ears, cheeks, and under the chin while avoiding the belly and root of the tail, are a few best practices.

Finka, along with nine other UK-based colleagues, have now followed up that study with another, trying to ascertain whether people actually follow this advice.

This, in fact, goes to the heart of the “aloof” cat stereotype. For many years, animal behaviourists have pointed out that humans trying to make acquaintance with cats tend to behave in ways that cats find deeply unsettling. Staring at them, for example, and making high-pitched, “Ooooh, who’s a widdle cuddly-wuddly kitty then” sounds are both quite aggressive behaviours in the cat world. Cats are generally not so keen on being picked up by strangers, either.

Paradoxically, they discovered that people who rate themselves as more knowledgeable of and experienced with cats are more likely than others professing less experience to disregard the best practices. “Cat people” don’t follow cat rules.

So, how does this play out in a laboratory setting?

Finka and her colleagues recruited 119 participants to complete a personality assessment and answer questions about their experiences with cats. Subjects were then invited into a laboratory setting and filmed as they interacted with three different adult cats previously screened for friendliness. Each session lasted five minutes.

“Participants were instructed to quietly enter the cats’ pen and to sit in the corner nearest to the entrance…” Finka and her colleagues described. “Participants were encouraged to interact with the cat as they normally would, with the exception of picking them up. Participants were also asked to remain in their seated position for the duration of the test, which effectively enabled cats to avoid human-interactions if they desired.”

On the one hand, people who’d spent the most time living with cats tended to score well. On the other, self-proclaimed “cat people”, “who rated themselves as more experienced and knowledgeable”, didn’t do as well as they might hope.

[They] were no more likely to follow best practices than others. In fact, they were more likely to be overly touchy, petting cats a lot more in both their favored (green) areas but also slightly more often in their disliked (red) areas.

And the “crazy old cat lady” stereotype?

Finka and her colleagues also found that people aged 56 to 75 and those who scored higher in neuroticism were more likely to hold and restrain felines in the sessions, something that most cats absolutely do not enjoy.

Big Think

Still, the researchers acknowledge that personality differences and selection could skew results differently. As Russian researchers conducting a decades-long breeding experiment with foxes found, selecting for individuals who showed the most inclination to interact with humans over a few generations resulted in foxes who were positively dog-like in their love for human company. They also evolved physical characteristics that were more dog than fox-like.

So, maybe crazy cat ladies and indulgent cats who get off on all the extra attention just find each other.