Table of Contents

Kurt Mahlburg

Kurt Mahlburg is a writer and author, and an emerging Australian voice on culture and the Christian faith. Since 2018, Kurt has been the Research and Features Editor at the Canberra Declaration. He is also a freelance writer, and a regular contributor at the Spectator Australia, MercatorNet, Caldron Pool and The Good Sauce.

“This book was written many years ago, and so we regularly review the language to ensure that it can continue to be enjoyed by all today.”

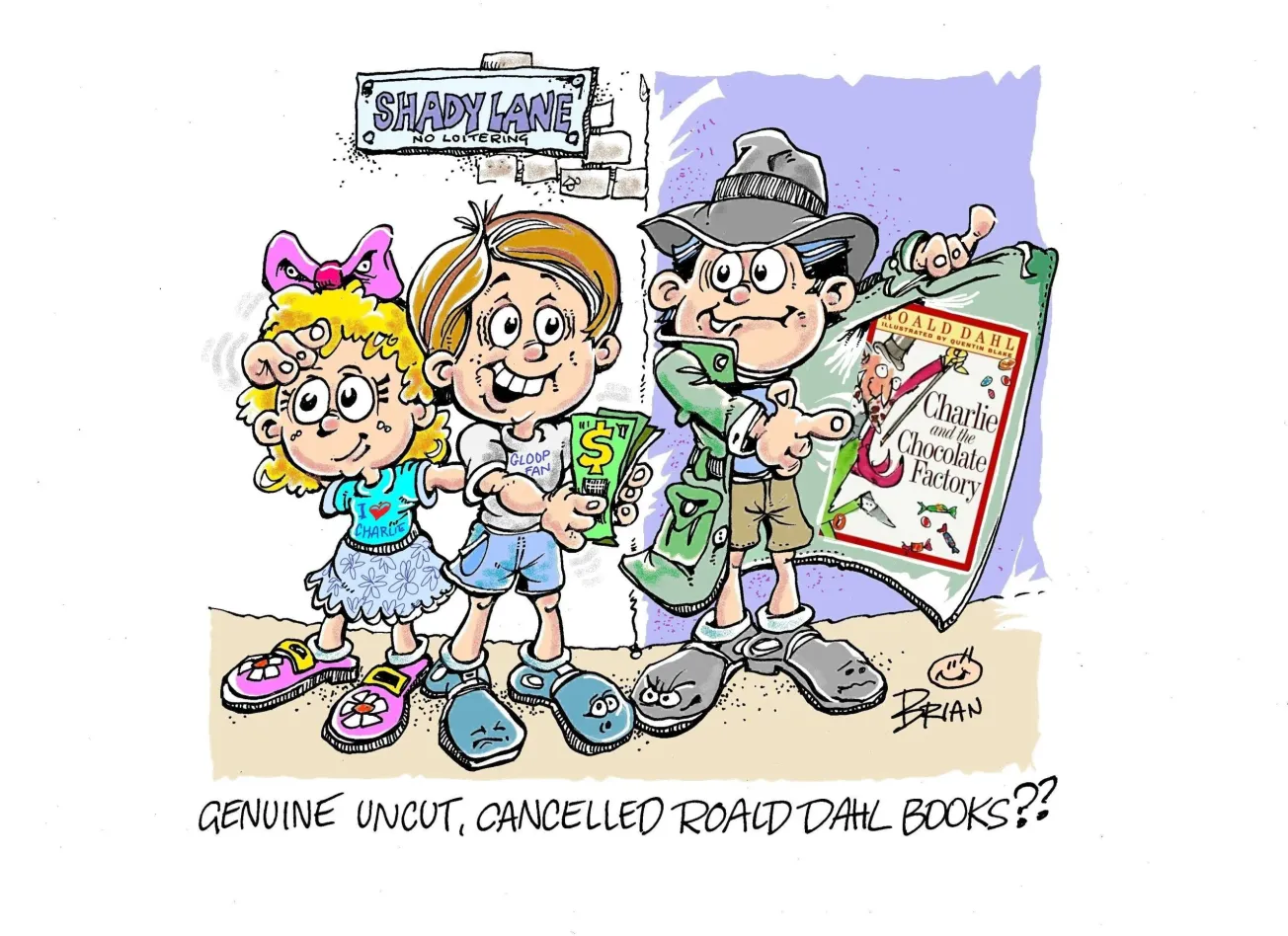

So read the ominous new words on the copyright page of the latest editions of Roald Dahl’s children’s books. Puffin, Dahl’s posthumous publisher and guardian of his legacy, has hired “sensitivity readers” to purge any language it deems offensive to new generations of readers.

Given the sensitivity of new generations — and the cheeky offensiveness in so much of Dahl’s corpus — it is an Orwellian recipe that would doubtless have Roald rolling in his grave.

Per The Guardian, Words like “fat” and “ugly” have been cut from every new edition of relevant books. We can only presume that fat and ugly people everywhere are cheering at their newfound social justice. Spare a thought for enormous people, however, who may feel miffed that Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’s insufferable Augustus Gloop is now among their number.

Yes, Puffin has not only made extensive culls of Dahl’s language but also inserted new words not penned by the author.

In a paragraph of The Witches explaining that witches are bald beneath their wigs is this novel addition: “There are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.” Is Puffin inferring that baldness is a shortcoming? It seems their sensitivity readers weren’t sensitive enough.

What good would Puffin’s Social Justice Warriors have been without taking the scalpel to all things gender? Behold, Dahl’s Oompa Loompas are no longer “small men” but “small people”. But wait: isn’t Puffin guilty of engaging in the erasure of small men?

And so is exposed the first (among many) fatal flaws when publishers hire sensitivity readers. How much sensitivity is enough? What is the limiting principle? Where does it end?

In a piece defending the practice, The Conversation explains that “a sensitivity read is a review of a book, script or game before it is published to help avoid portraying marginalised people and cultures inaccurately, including unintentionally using stereotypes or causing upset”.

“Thanks to increasing awareness of cultural representation,” the article continues, “sensitivity readers are now routinely employed before a book is published, if the author is writing about cultures outside their lived experience”.

Granted: giants, witches and Oompa Loompas did indeed fall outside of Roald Dahl’s lived experience.

On a more serious note, here we observe another fatal flaw in the use of sensitivity readers. By seeking to avoid stereotyping subgroups, publishers who hire sensitivity readers do precisely that when they presume all members of a “marginalised” group think, feel, and get offended in identical ways.

Since when does having a certain skin tone, genital configuration or sexual orientation automatically convey unrivalled expertise in how all people of that sex, ethnicity or orientation experience the world?

Kat Rosenfield is an American author who has worked with sensitivity readers and has provided extensive commentary on the subject. Writing for Reason, she muses:

The irony is that sensitivity reading is, in itself, an exercise in exactly the kind of offensive generalising it purports to help authors avoid — not just in the way it traffics in crude stereotypes about how people of a given race, gender, or sexual orientation move through the world, but in whose interests it ultimately serves.

Whose interests does it serve? Writes Rosenfield, “this is a practice driven primarily by the fears of privileged editors, agents, and publishers” eager to protect themselves from reputational damage and appear to care about the latest moral fad.

And that at a discount. According to Rosenfield:

They’re cheap. The average cost of a sensitivity read is a few hundred dollars per manuscript, and it’s a freelance job. This made it a godsend to publishers who wanted to merely look like they were giving people of colour a seat at the table but didn’t want to go to the trouble of buying all those additional chairs. Retaining a freelance stable of racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities created the appearance of diversity for a fraction of the cost.

Never has righteousness been so affordable. All hail, Puffin, for its valiant efforts!

On the same publishing page referenced earlier, Puffin asserts that “the wonderful words of Roald Dahl can transport you to different worlds and introduce you to the most marvellous characters”.

Only now a little less wonderful, a little less different, a little less marvellous.