Table of Contents

Robin Koerner

Robin Koerner is a British-born citizen of the USA, who currently serves as academic dean of the John Locke Institute. He holds graduate degrees in both physics and the philosophy of science from the University of Cambridge (U.K.).

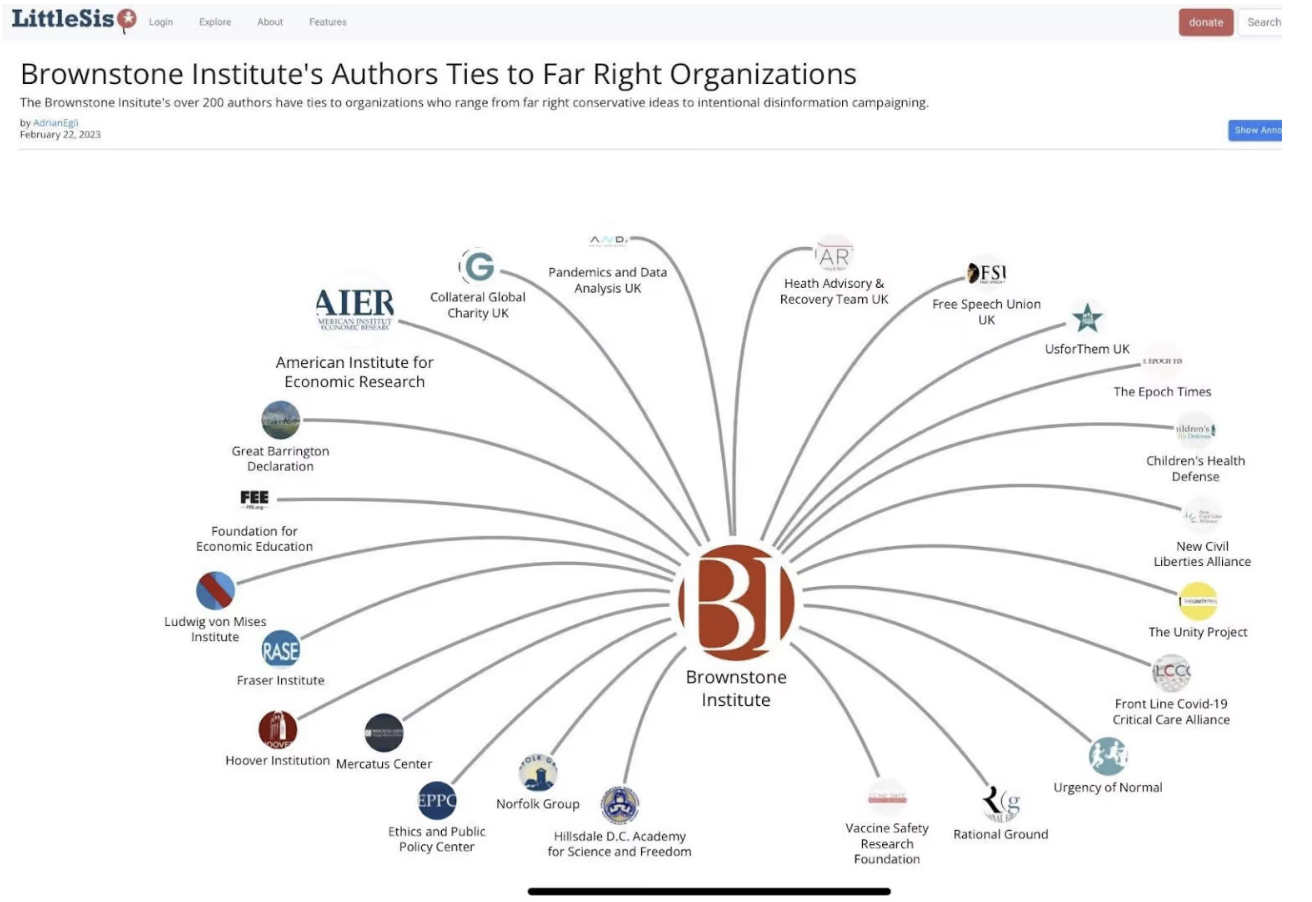

Brownstone Institute recently found itself at the middle of yet another one of those silly spider diagrams of organizations, under the supposed-to-scare-you title of “Brownstone Institute’s Authors Ties to Far-Right Organizations.”

Here it is.

I suspect this means we are doing something right (no pun intended) because it is almost certainly a signal that we are beginning to have an impact.

I don’t know every one of the organizations in this diagram – but none of those that I do know (a good few) can be described as ‘far-right’ with both a straight face and a grade-school understanding of basic political terminology or history.

Rather, the diagram is a perfect example of a perennial political phenomenon and the operation of a rule of thumb that I came up with a few years ago.

I need a better name for it, but for now, let’s call it the “When They Call You ‘Far-Right’, You’re Probably Right” Rule.

It goes as follows.

Any principle-based movement that opposes a long-standing government policy that has mainstream support but in fact involves a huge abrogation of rights or representation will be labeled “far-right” once the movement begins to attract mainstream attention.

Examples of the Rule

Although I have been a rights activist continuously since I became interested in politics around 2010, my three most publicly visible political contributions have been 1) in support of Ron Paul’s presidential candidacy in the USA in 2012, 2) in support of honouring the result of the Brexit referendum in the UK in 2016 and 3) against lockdowns and coerced “vaccinations” during the COVID pandemic.

Regarding the first of those, I was responsible for creating the largest coalition of voters for the would-be Presidential nominee Ron Paul. They were called Blue Republicans and the term, which I coined, referred to Democrats and Independents who responded positively to the progressive case I made for Paul’s candidacy in a viral article in the Huffington Post.

In that article, I pointed out that Dr Paul was the one potential nominee who had a track record that was anti-war, pro civil-rights and anti corporate cronyism. I suggested that my readers who supported those things and had voted for Obama in 2008 (of which the Huffington Post had many because it is a left-wing news and opinion site) should, having seen Obama’s first-term track record, stick to their principles and join the Republican Party for just one year to put a pro-peace, pro-rights, anti-corporatist candidate on a presidential ticket. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Democrats and Independents agreed with me and did just that.

At that time, the mainstream media were consistently calling Dr Paul (a self-identified anti-war libertarian), “ultra-conservative”. He is many things – but that is not one of them, as anyone who has listened to any of his speeches for 10 minutes can easily see. Moreover, this was a man who happily withstood the boos and jeers of the Republican audience at a primary debate by refusing to go along with the various rights-violating positions and foreign policy interventions that were advanced by his opponents.

Around the same time, on the other side of the pond, a few British figures were pointing out the anti-democratic nature of the European Union (EU). Most notable among them were Nigel Farage and Daniel Hannan (MEP). For years, the media labelled them “far-right” or some version thereof. Again, these advocates were nothing of the kind: rather, they were classical liberals who merely objected to a lack of transparency and democratic representation by the EU government and the overreach of that body into the personal lives and decisions of Europeans.

And now, here we are again. Brownstone Institute is finally attracting significant attention for a counter-narrative that suggests that, during the Covid pandemic, the government overreached; that it did harm to our freedoms and even our bodies, and that this harm was enabled by both a lack of transparency by the state and the tendency of citizens to trust the agents of the state way too much.

As a result, we Brownstone authors, who exhibit a very wide range of political views, are targeted with the same old, tired: “Don’t listen to them; they are ‘far-right’.

The Psychology Behind the Rule

Why that particular slur? Why is that the lie that our illiberal attackers think will serve them best? And when do they deploy it?

Interestingly, the answer to this question is the same as the answer to the question of why the Hammer and Sickle do not elicit the intensity of disgust that the Swastika does, despite at least as much evil having been done in the name of the former.

It is an answer that can be found buried in Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, and it is an answer that has been empirically tested in the burgeoning field of Humanomics by such brilliant experimental economists as Vernon Smith (a Nobel Memorial Prize winner) and Bart Wilson.

Namely, we judge others not by the outcome of their actions but by what we infer of their intention. Even as our rational minds tell us we would do better to measure our compassion by the good that we do and not by the strength of our intention, we simply cannot turn off the system in us that generates moral judgments from what we believe about other people’s motivations – even when we are wrong about those motivations and quite regardless of the real-world consequences of their actions.

Now, add to this well-established fact of human nature what I have elsewhere called the “Fallacy of the Assumed Paradigm”, which can also be simply stated:

If I support policy (or course of action) X because I have a good intention G, then if you are against X, you must not share the good intention G.

This is a fallacy because it assumes that everyone believes the same things about everything else in the world (everything that is not X and G) – which of course they don’t. (No two people share an identical paradigm.)

So, for example, if I experience my support of X (coerced “vaccination”) as following from my good intention G (to end a pandemic), then I likely have beliefs about the safety and effectiveness of X, the trustworthiness of the sources of my information about X, and so on.

The person who is caught in the fallacy fails to appreciate that another person who would wish to achieve the same goal G (to end a pandemic) may not support the same policy X (coerced “vaccination”) simply because he does not also share numerous other beliefs that link the policy to the goal (such as the safety or effectiveness of the “vaccine” or the trustworthiness of relevant sources of information). Failing to appreciate this, the well-intentioned supporter of the policy in question wrongly imputes ill-intent (“He must not care about the pandemic”) to her opponent.

Why would somebody do that rather than simply accept in good faith her opponent’s disagreement on the facts? Here, the idea of “projection” is relevant. Whereas sometimes people can respectfully agree to disagree on an issue, a person who has justified a policy of imposing upon, and even harming, some people for what she believes is a greater good is a person for whom an admission of error would also be an admission of having done something that, by her own argument, was morally bad. Such a thing can threaten a person’s entire sense of self and many other beliefs that she lives by.

We are now able to understand why fervent supporters of a mainstream-endorsed, widely accepted policy that involves ostensibly well-intended, massive state action that has negative consequences so often call their opponents ‘far-right’ when those opponents start making political headway.

That her opponent opposes her preferred policy of massive state intervention puts him, in her eyes, on the political right; that he is doing so with ill-intent puts him, in her eyes, on the far right.

The ‘far right’ slur begins to be hurled when those at whom it is targeted are beginning to succeed among the wider population in casting doubt on the policy that has until that time prevailed unchallenged. Only when challenges to the statist quo begin to be taken seriously in the media, culture and politics, do its supporters feel the need to defend their position.

When the facts are not with them, they have few options other than resorting to ad hominem attacks – and no such attack better fits the false inference of ill-intended opposition to state action than ‘far-right’. By the same token, no attack better fits the purposes of state actors with an interest in containing a minority opinion that threatens to expose their designs.

‘Far-right’ is a slur: it is the N-word of politics. All it usually means is, “Here are the people who got far more right than we did.”