Table of Contents

This series is designed to help people to understand modern technology, and become more confident in using computing devices. It is not designed to educate experts.

The author is involved in tutoring older students at SeniorNet, a New Zealand wide organisation. SeniorNet hopes that students will feel more confident in using their computing devices as a result of the learning opportunities offered. This series of articles shares that hope.

You may have noticed if you’ve read my bio, that I’m a supporter of free open-source software. You may have wondered what that is. Let me elucidate.

What is open source software?

Open source software is computer software with source code that anyone can inspect, modify, and enhance.

“Source code” is the part of software that most computer users don’t ever see; it’s the code computer programmers write and edit to change how a piece of software—a “programme” or “application”—works. Literally, it’s the recipe for making a piece of software or app. This source code is then run through another programme called a compiler that converts the source into the usable programme.

Programmers who have access to a computer programme’s source code can improve that programme by adding features to it or fixing parts that don’t always work correctly.

Here is an open-source analogy that may help you to better understand what I’m about.

What’s the difference between open-source software and other types of software?

Some software has source code that only the person, team, or organisation who created it, and maintains exclusive control over it, can modify. People call this kind of software “proprietary” or “closed source” software.

Only the original authors of proprietary software can legally copy, inspect, and alter that software. And in order to use proprietary software, computer users must agree (usually by signing a license displayed the first time they run this software) that they will not do anything with the software that the software’s authors have not expressly permitted. Microsoft Office and Microsoft Windows 10 are examples of proprietary software.

Windows 10 EULA (End User Licensing Agreement).

Microsoft Services Agreement (Microsoft consumer products, websites and services listed)

Open source software is different. Its authors make its source code available to others who would like to view that code, copy it, learn from it, alter it, or share it. LibreOffice and the GNU Image Manipulation programme (The GIMP) are examples of open source software.

As they do with proprietary software, users must accept the terms of a license when they use open source software—but the legal terms of open source licenses differ dramatically from those of proprietary licenses.

Open source licenses affect the way people can use, study, modify, and distribute software. In general, open source licenses grant computer users permission to use open source software for any purpose they wish. Some open source licenses—what some people call “copyleft” licenses—stipulate that anyone who releases a modified open source programme must also release the source code for that programme alongside it. Moreover, some open source licenses stipulate that anyone who alters and shares a programme with others must also share that programme’s source code without charging a licensing fee for it.

By design, open source software licenses promote collaboration and sharing because they permit other people to make modifications to source code and incorporate those changes into their own projects. They encourage computer programmers to access, view, and modify open source software whenever they like, as long as they let others do the same when they share their work.

The GIMP GNU General Public License

Is open-source software only important to computer programmers?

No. Open source technology and open-source thinking both benefit programmers and non-programmers. The open-source philosophy has also underpinned much of how science has been done over centuries. See what Isaac Newton did for science.

Because early inventors built much of the Internet itself on open source technologies—like the Linux operating system and the Apache Web server application—anyone using the Internet today benefits from open source software.

Every time computer users view web pages, check email, chat with friends, stream music online, or play multi player video games, their computers, mobile phones, or gaming consoles connect to a global network of computers using open source software to route and transmit their data to the “local” devices they have in front of them. The computers that do all this important work are typically located in distant places that users don’t actually see or can’t physically access—which is why some people call these computers “remote computers.”

More and more, people rely on remote computers when performing tasks they might otherwise perform on their local devices. For example, they may use online word processing, email management, and image editing software that they don’t install and run on their personal computers. Instead, they simply access these programmes on remote computers by using a Web browser or mobile phone application. When they do this, they’re engaged in “remote computing.”

Some people call remote computing “cloud computing,” because it involves activities (like storing files, sharing photos, or watching videos) that incorporate not only local devices but also a global network of remote computers that form an “atmosphere” around them.

Cloud computing is an increasingly important aspect of everyday life with Internet-connected devices. Some cloud computing applications, like Google Apps, are proprietary. Others, like ownCloud and Nextcloud, are open source.

Why do people prefer using open source software?

People (like me) prefer open source software to proprietary software for a number of reasons, including:

Control. Many people prefer open-source software because they have more control over that kind of software. They (or others) can examine the code to make sure it’s not doing anything they don’t want it to do, and they can change parts of it they don’t like. Users who aren’t programmers also benefit from open-source software, because they can use this software for any purpose they wish—not merely the way someone else thinks they should.

Training. Other people like open source software because it helps them become better programmers. Because open-source code is publicly accessible, students can easily study it as they learn to make better software. Students can also share their work with others, inviting comment and critique, as they develop their skills. When people discover mistakes in programmes’ source code, they can share those mistakes with others to help them avoid making those same mistakes themselves.

Security. Some people prefer open-source software because they consider it more secure and stable than proprietary software. Because anyone can view and modify open-source software, someone might spot and correct errors or omissions that a programme’s original authors might have missed. And because so many programmers can work on a piece of open-source software without asking for permission from original authors, they can fix, update, and upgrade open-source software more quickly than they can proprietary software.

Stability. Many users prefer open-source software to proprietary software for important, long-term projects. Because programmers publicly distribute the source code for open-source software, users relying on that software for critical tasks can be sure their tools won’t disappear or fall into disrepair if their original creators stop working on them. Additionally, open-source software tends to both incorporate and operate according to open standards.

Community. Open source software often inspires a community of users and developers to form around it. That’s not unique to open source; many popular applications are the subject of meet ups and user groups. But in the case of open source, the community isn’t just a fan base that buys in (emotionally or financially) to an elite user group; it’s the people who produce, test, use, promote, and ultimately affect the software they love.

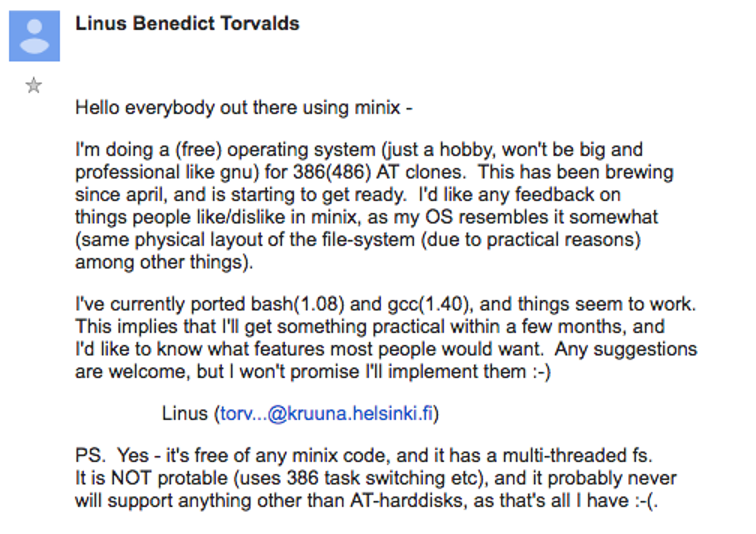

Here is arguably the most famous communication inviting people to join a community, from 1991.

Cost. Much open source software comes “free”, that is you can legally obtain and use it without paying either an up front purchase price, or monthly rental. This can be a major saving. Of course, you can pay in other ways if you wish. Donating funds, time or expertise to a project, for instance.

To give you an idea of the cost difference (these versions are Windows 10 versions, except for Manjaro Linux).

Operating System

Microsoft Windows 10 Home from the Microsoft Store NZ NZ$259.00 (download over the internet)

Manjaro Linux KDE desktop from osdn.net NZ$0.00 (download over the internet)

Graphics

Adobe Photoshop from Adobe.com A$358.66 pa. (NZ$387.95 pa,).

The GIMP from gimp.org. NZ$0.00 (download over the internet)

Office Suite

Microsoft Office Home & Business 2019 from the Microsoft Store NZ NZ$439.00 (download over the internet)

LibreOffice from libreoffice.org NZ$0.00 (download over the internet)

(In a forthcoming article I will talk about some of the open source software I use and love).

Doesn’t “open source” just mean something is free of charge?

No. This is a common misconception about what “open source” implies, and the concept’s implications are not only economic.

Open source software programmers can charge money for the open source software they create or to which they contribute. But in some cases, because an open source license might require them to release their source code when they sell software to others, some programmers find that charging users money for software services and support (rather than for the software itself) is more lucrative. This way, their software remains free of charge, and they make money helping others install, use, and troubleshoot it.

While some open source software may be free of charge, skill in programming and troubleshooting open source software can be quite valuable. Many employers specifically seek to hire programmers with experience working on open source software.

Red Hat Linux became the first billion dollar Linux company (in 2012) who gave away it’s product for free.

Open Source Beyond Software

The world is full of “source code”—blueprints, recipes, rules—that guide and shape the way we think and act in it. Many believe this underlying code (whatever its form) should be open, accessible, and shared—so many people can have a hand in altering it for the better.

Here are articles about the impact of open source values on all areas of life—science, education, government, manufacturing, health, law, and organisational dynamics. There are communities committed to telling others how the open source way is the best way because a love of open-source is just like anything else: it’s better when it’s shared.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please share it.